#9 The problem with financing the circular economy is the economy

not finance, not business models and not technology

Hi all,

One of my favourite topics lately, which I haven't been writing much about, is the circular economy. And there are a few reasons why I haven't delved into it as much as I'd like.

Firstly, I'm keen on promoting all the positive, sustainable energy within circularity: initiatives that aim to reduce resource consumption, develop better business models based on sharing, and shift towards product-as-a-service models. Considering the current need for it, it's essential to foster positivity in this space.

Secondly, there's too much to cover. I want to explore the intricate relationship between the circular economy and growth (or lack thereof), the prevalence of rebound effects, the pitfalls of certain business models, the distinction between circular resource flows and monetary flows, and the concept of circular finance. It's quite an extensive range of topics, especially for a single newsletter.

Typically, I would start at a conceptual level, discussing the relationship between the circular economy and degrowth strategies, examining worldviews and the laws of entropy, and illustrating the challenges of achieving a circular world within a linear framework. This is where I feel most comfortable—operating at the systemic level. However, I've realised that focusing solely on these theoretical aspects might not drive the economic change we need most.

For a change, I've decided it might be more practical to start with a topic that's more immediately applicable: circular finance. I've already gathered some insights on this over the years, and I believe there's still some misunderstanding surrounding it. I often hear statements like 'we need to understand the circular economy better' or that it's primarily about technology or new business models. While these aspects are undoubtedly relevant, I argue that at its core, circular finance boils down to simple economics: grappling with market dynamics, particularly within the context of linear markets, when attempting to finance circular initiatives.

Only when we understand the circular economy as what it is, economy, can we start discussing financing it (or not).

As always, at the end, some news.

Enjoy

Markets and the circular economy

There are many definitions for a circular economy, but let’s keep it very simple here: it is, in the end, about using less renewable and non-renewable resources. And that is (instead of the academic and practitioner’s attention for circularity) not speeding up.

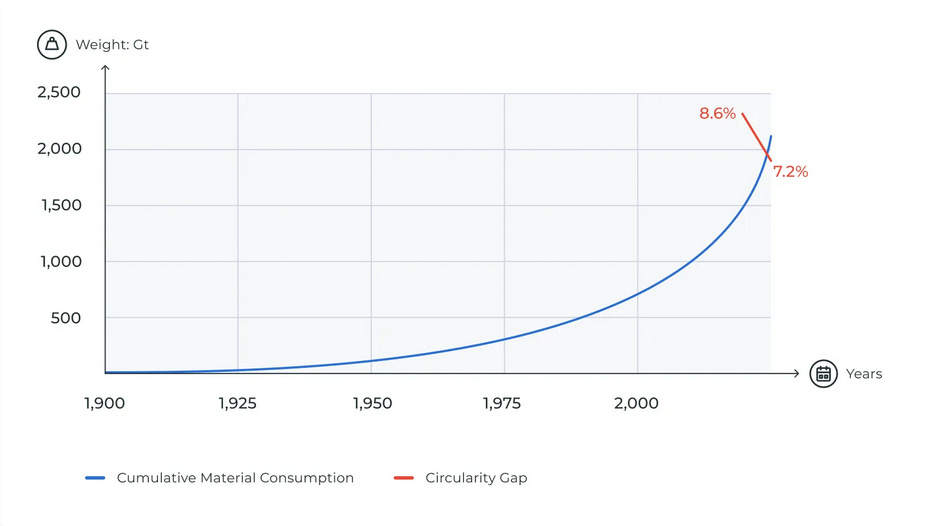

On the contrary, according the Circularity Gap Report 2024 the world has become less circular. The share of secondary materials consumed by the global economy decreased from 9.1% in 2018 to 7.2% in 2023—a 21% drop over five years. In just the past six years alone, we have consumed over half a trillion tonnes of materials—nearly as much as the entirety of the 20th century—the shocking reality.

The concept of a circular economy, even before it became a recognized research, business, or policy theme, was articulated by Herman Daly: extracting non-renewable resources should be balanced by developing renewable substitutes. In contrast, renewable resources should be extracted at a rate equivalent to their regeneration rate. This entails that in a (steady state) economy; the purpose is to optimise all the stocks of matter in the economy and minimise the throughput (input and output), which is at odds with steering on GDP growth, which maximises throughput in the economy.1

What most of the Circular Economy research does (and that is not so surprising) is concentrate on those resource flows. And, of course, there is a vast other field of circular business models.

However, one of the problems of the research on circular economy is the lack of economics. To take a straightforward approach, take the figure below. I have used it for over seven years in various presentations, but I fear the clue is often missed.

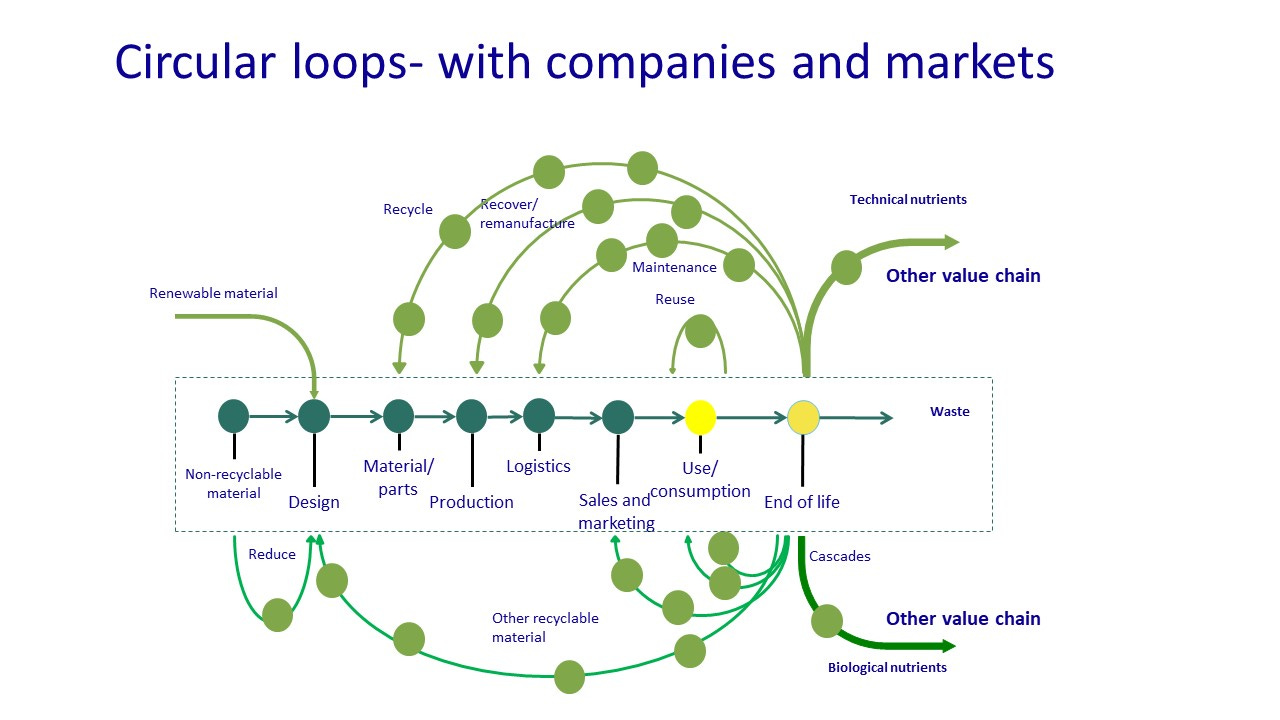

Here, you see the standard Ellen McArthur Foundation butterfly diagram (but then rotated 90 degrees) and the different loops, currently often named R-strategies. The only thing I did was add the dots (companies/business models). But the point that I want to make here is that transactions between companies (the dots) to achieve those R-strategies will only happen if there is a place or coordination mechanism between those companies. Economists expect that, not surprisingly, markets would be the most logical way to get the job done.2

Market imperfections

And there it comes (and that is why financing the circular economy is so tricky): there are many reasons that markets can not work how they are supposed to.

The economic literature describes a long list of market imperfections that make the emergence of markets, and thus the emergence of circularity in a circular economy, difficult or even prevent. You can distinguish between primary and secondary system failures. In the case of primary system failure, the main focus is on the failure of markets to function optimally; in the case of secondary system failure, it is mainly the transition or context variables that cause markets to be absent or not functioning optimally.

Primary system failure is most often described in the standard literature. In circular economics, however, this primary failure has yet to be applied, or only to a minimal extent. Nevertheless, these forms of market failure are an essential reason why specific circular markets do not materialize:

- Negative externalities: Market prices do not reflect the social costs associated with producing and consuming goods or services. The most well-known example of this at the present juncture is the social costs related to CO2 emissions. Another example of this is the failure to correctly price environmental impacts associated with the extraction and depletion of resources. Please price these effects to avoid a competitive disadvantage for circular alternatives.

- Imperfect market organisation: Another classic economic problem is too little competition or too little demand: monopoly on the supply side, monopoly on the demand side and everything in between. Restrictions on the number of demanders and suppliers lead to sub-optimal prices if there is a market, but often also to markets needing to be created.

The market power of a monopoly company is often both the cause and effect of entry barriers. Such barriers may be technological barriers and the size of the market. The latter is often a barrier to the emergence of a circular economy. Only if there is a sufficient supply of residual flows - for example, plastics - will it be possible to establish a competitive business model. Lack of volume 'closes' the market to more suppliers.

However, the demand side of the market also often creates barriers to the emergence of a circular economy. For example, specific waste streams or products can only be used by a limited group of demanders. This is particularly true for highly innovative applications. The more specific the waste stream, in terms of material or geographical dependence, the greater the likelihood of this problem.

The combination of limited demand and limited supply also occurs. Consider, for example, an eco-industrial park where the residual flow from one company (e.g. heat) is the input for the other company. With only one supplier and one buyer, there is maximum chain dependence and no real market.

Solving this market problem can be challenging and involves coordination costs and risks to a perfectly functioning market. It can very well lead to a situation where there is no market and, therefore, no circularity.

- Information problems: Lack of information is a third market problem. Theoretically, a free market has complete details on all supply and demand. Practice is different. The problem lies not so much in the availability of material for reuse or products that could be better used but in bringing supply and demand together. It is for sure that attempts are now being made to map out materials using a materials passport. Moreover, transaction costs bring together the supply and demand of unused raw materials and products. If these transaction costs are too high, this can cause a market to malfunction or (further) develop. In practice, this often turns out to be the case. New technologies such as digital platforms have contributed significantly to reducing these costs, but in addition to search costs (e.g. searching through pages on marketplaces), physical costs, such as retrieving items, remain. Information asymmetry also persists because the seller knows more about the quality of a product or raw material than the buyer. The more heterogeneous the products, the more difficult (or expensive) it is to eliminate this asymmetry.

This type of information problem limits the degree of circularity of an economy.

In addition to these more or less standard forms of market failure, secondary system failure creates additional problems that explain why markets do not work or do not emerge.

One form of this is innovation failure. If companies are afraid that they will not be able to reap the benefits of their investments in innovation themselves, they may not invest enough. These 'leakage effects' also play a role in the circular economy context. Companies will invest less in circular design and technology if others can easily replicate it.

Innovation failure is also the cause of a system crashing in a specific direction. If a lot has been invested in a particular direction, for example, in linear technology, it is rational to continue to do so, at least with a short investment horizon. This 'lock-in' makes circular alternatives less attractive. This problem is close to transformation failure: economic actors need to move away from a certain direction of thought and innovation. This goes beyond technology. Laws and regulations, consumer behaviour and habits continue to perpetuate this direction.

Another possibility is transition failures. Transitions, defined as society-wide changes that go beyond single sectors and involve fundamental and interrelated changes in technology, organisation, institutions and culture, are non-linear shifts from one dynamic equilibrium to another. A circular economy can be interpreted as such a system change. There is no guarantee that efficient markets can cope with all transitions only based on price signals and individual preferences. Transition failures can occur, for instance, through path-dependence, lock-in, diversity of options, bounded rationality and uncertainty. Primarily, sustainability transitions intended societal changes with a (democratically decided) objective instead of market-induced transitions due to (technological) innovation, which requires more changes and transition.

A long story. However, all these market imperfections are essential to understanding why scaling up the circular economy is so difficult.

Financing the circular economy

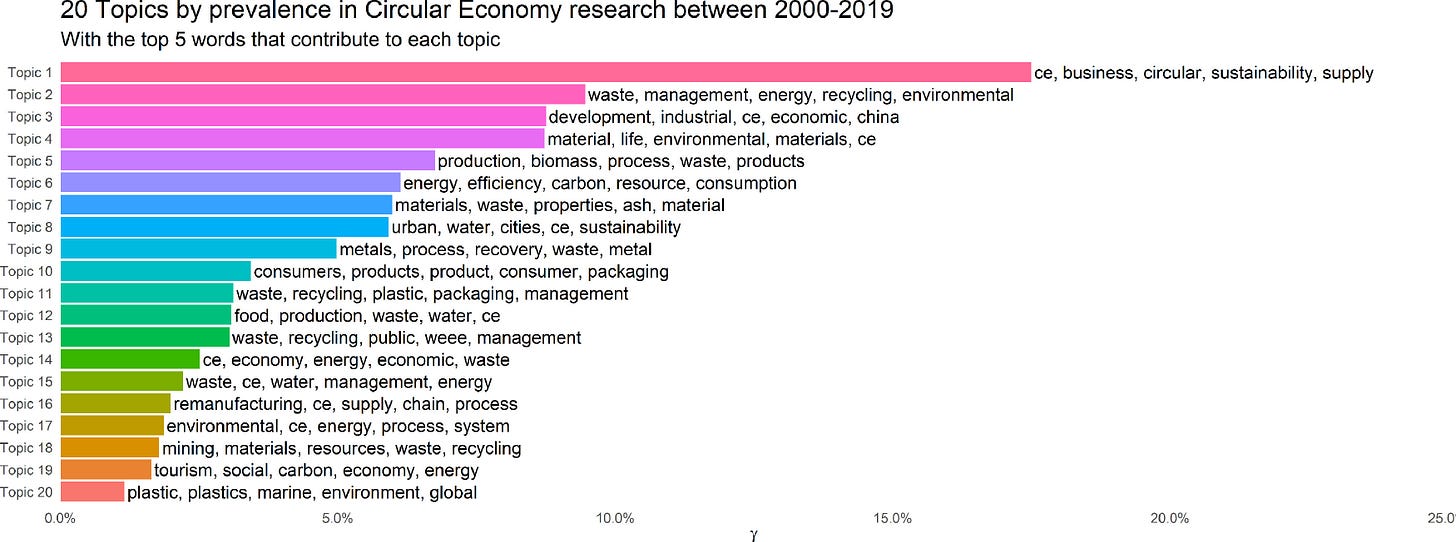

From the top-20 topics discussed in the academic Circular Economy literature, finance is not one of them.

However, in many papers, it is mentioned as a barrier. Also, financial institutions (for instance, see this finance guidebook by Dutch banks) work on understanding why financing the circular economy is challenging. From their 40 risk factors, a lot relate to the business model, and only a few relate to markets, as explained above. Also, some are common to the circular economy. For instance, the quality of management always matters. It might be more critical if other risks are involved.

More research is needed about financing the circular economy. This overview article states some problems related to markets and transitions, but some examples seem (again) common to other than CE business.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the various building blocks related to finance challenges. Yet, it overlooks a crucial aspect of finance: the inability to substitute public finance with private finance. It critically depends on anticipated returns and risks intricately linked to market dynamics.What is evident is the presence of linear risks associated with prevailing practices. If the circular transition accelerates, companies that fail to keep pace will inevitably lose their competitive edge. Conversely, even if the transition towards circularity falters and resources become depleted, the companies most reliant on them will suffer the most significant impact. These risks encompass market dynamics, operational challenges, reputational concerns, and legal complexities. They may manifest when resources become scarcer or regulations necessitate more sustainable approaches. However, these linear practices still need to be factored into market valuations. Consequently, they pose a lesser concern for financiers.

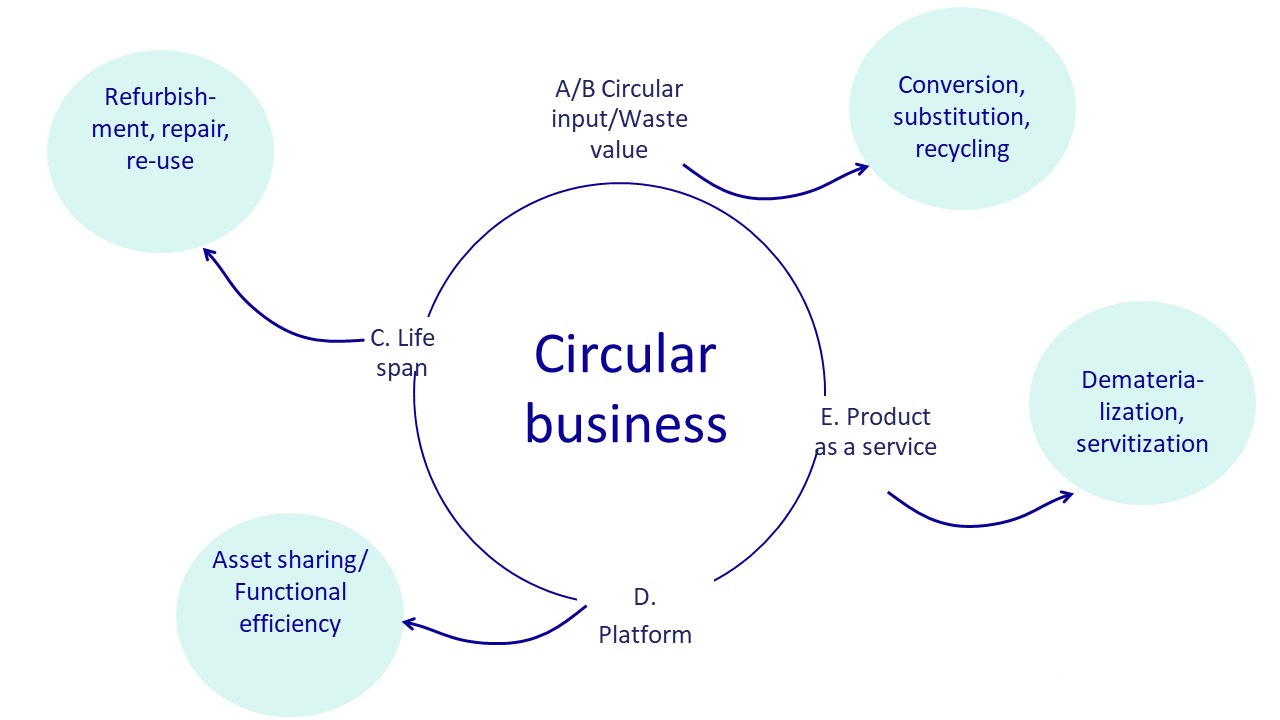

Let's examine some popular circular business models (outlined below) without claiming to provide a definitive or exhaustive solution.

Business models A to E represent ideal types, with the blue balloons indicating their intended outcomes. Each of these models introduces unique dependencies compared to traditional business practices. In the table below, I have tried to categorize these dependencies.

When considering innovation risks, the applicability to all circular business models is only sometimes universally conclusive. Take, for instance, waste processing and repair services (think of your tailor); these are not necessarily groundbreaking innovations. Moreover, innovation risks, if present, are truly distinctive only when they pertain to specific aspects such as resource treatment or product design. Therefore, while a platform may entail risks, they may not necessarily be directly linked to circularity innovation. Some Furthermore, specific operational changes can affect cash flow and balance sheet management, particularly in Product-as-a-service (PaaS) models. However, PaaS models, like lease cars, have existed for a considerable time. Thus, other factors must contribute to the issue's complexity.

Those other factors differentiate a circular economy from a linear economy: chain dependence, market size and share, transaction costs and transition risks.

Chain dependence is a crucial feature of circularity that introduces new risks and relates to the market failures mentioned above). If there are only a few suppliers of a resource (e.g. waste stream, waste heat), new dependencies are introduced. From a financial perspective, this equals risks. There is no easy way to overcome this.

Related to this, some business models heavily depend on market size or market share to be financeable. Consider, for instance, PaaS models that need a specific market size to make repair logistics cost-efficient, reducing costs. But think also about sharing models, where a large enough network (and also share in networks) is crucial to have enough relevance. Only then demand and supply can sufficiently be matched.

What is quite fundamental is that transaction costs will usually be higher (in a linear setup). This involves responsible sourcing, more coordination costs (in the value chain), and more aftercare (like guarantees if done correctly).

And, of course, given the current linear model, transition risks are enormous. That is also what we currently see. A lot of circular companies have challenges to scale up.

How do we get somewhere?

This all sounds negative. It is not negative but realistic. What we see is those companies that work on the circular economy either do that as a sideline of their core business (large companies that fund themselves CE experiments, like Patagonia, Ikea, et cetera), that the companies are led by simply excellent entrepreneurs or that they have a small nice (although this is rare). What companies can do to reduce some of the risks (such as chain dependencies) is vertical integration to reduce supply chain risks and diversify products and services to reduce other risks, from sourcing to transaction costs (although it can also add complexity).

My conclusion is that we should change the rules of the market to make it financeable. A few fundamental changes:

True prices

Shift taxes from labour to resources

Change of ownership structures so that communing becomes the new normal

In addition, policies for sufficiency (that people want to buy less, need less, but what they need is more durable) would be helpful.

To conclude, there is no guarantee that scaling up and financing circular business will lead to less resource use. In the end, rebound effects and other system-wide effects might still lead to more resource use. Circular business can create a further linear lock-in, mainly when businesses concentrate foremost on (linear!) waste streams. But that is not for this week…

In the news

A recent study in Nature offers insights into effective governance, drawing upon Ostrom's work on Collective Property Rights (CPR).

The climate strategy of the European Commission: Mind the demand side: Goals become paper tigers when they are practically unattainable. And if those paper tigers aren't even ambitious enough, they can quickly end up in the trash. That's how we see the goals set by the European Commission for 2040 to combat climate change.

This article highlights that environmental costs are already soaring, without that companies are open about it. It is not only energy use but also water use that is ballooning

Due to be published later this month by the UN’s International Resource Panel, the global resource report is expect to highlights how global consumption of raw materials, having increased four-fold since 1970, is set to rise by a further 60% by 2060.

Take care,

Hans

Although it could also be different, like reciprocal relationships or vertical integration (coordination within a firm - sometimes a solution).