The climate strategy of the European Commission: Mind the demand side

An energy transition does not equal a renewable energy transition

Goals become paper tigers when they are practically unattainable. And if those paper tigers aren't even ambitious enough, they can quickly end up in the trash. That's how we see the goals set by the European Commission for 2040 to combat climate change. The plan lacks ambition because the EC aims for an EU that significantly exceeds its 'fair share' of greenhouse gas budgets. The plan is unrealistic because the goals set by the European Commission focus on changes to the production side of the economy, rely on unproven technology, and fail to address the necessary changes in consumption and behaviour. Without a credible plan for all citizens – including farmers – livelihood security is at risk in the short and long term. And an inclusive transition is now more needed than ever before. In this article, we explain the lack of ambition and realism in the EC plans and propose ideas for a plan that genuinely addresses the scale of the crisis and provides citizens with a fair perspective. A significant omission currently is that only limited policies are incorporated to address the demand side of the energy transition.

Too low ambition

The European Commission (EC) proposes a net reduction target of 90% in greenhouse gas emissions by 2040. This represents a slight tightening compared to existing legislation. No specific target has been set between the 55% reduction by 2030 and net zero by 2050. Achieving a 90% reduction by 2040 requires us to decarbonise net emissions faster than linearly between 2030 and 2050. Compared to the Commission's previous targets, this is a step forward for the climate. It is also faster than our current trajectory, as we are falling behind on the 55% target for 2030, as indicated in the EC's latest progress report from December.

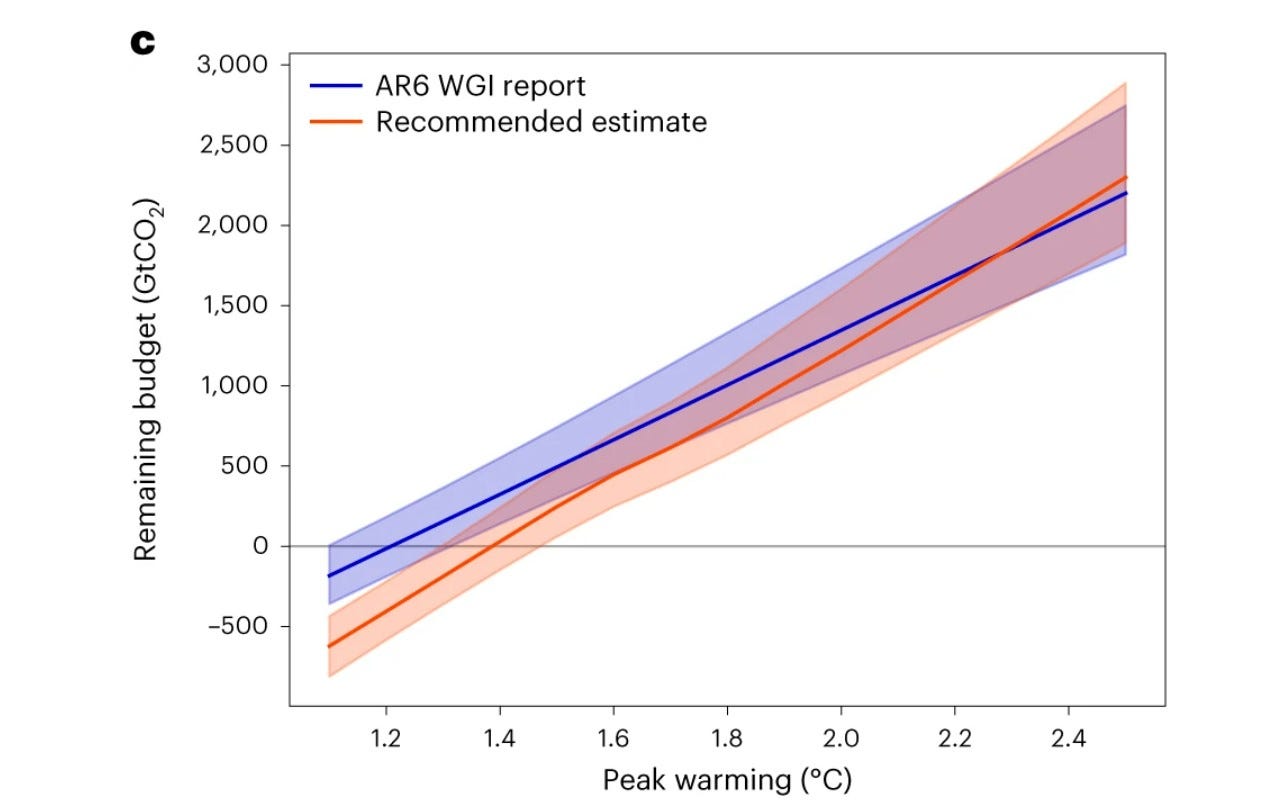

The EC has drafted a plan expected to result in approximately 16 GT of greenhouse gas emissions (in CO2 equivalents) between 2030 and 2050. This is higher than the 11 to 14 GT recommended by the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change. The advisory board indicated that even 11 to 14 GT is actually too much. There are at least ten ways to argue how much a country or region 'should' emit if we want to limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius globally. This can be based on equal emissions per capita or on the principle of 'strongest shoulders bear the heaviest burden'. Whichever of these principles you choose, with emissions of 11-14 GT between 2030 and 2050, the EU exceeds its 'fair share', according to the scientific advisory committee of the EC. They therefore recommend, in addition to rapid domestic reduction measures, assisting with emission reduction in other countries. However, no concrete goals are included in the EC's plan. Additionally, the Scientific Advisory Committee based their advice on IPCC figures from 2022. This report estimated the remaining CO2 budget at 500 GT globally. Since this IPCC report, climate science has further developed, and we may have overestimated the remaining carbon budget. The global budget could be only half of what was previously thought.

Achieving the ambition of 90% by 2050 will be quite challenging, as the plan is already riddled with gaps and compromises. For example, no target is included for methane and nitrogen emissions for the agriculture sector in 2040, and quantitative targets for decreasing CO2 emissions for the agriculture sector have also been removed compared to earlier versions. This kind of dynamic is likely what Hoekstra means when he says that the presented plans are not so much a goal but more of a "dialogue". A transition plan that starts with the approach we are really going for unless an entrenched interest opposes the change, is doomed to fail.

Unrealistic Plan

To achieve a 90% reduction, the EC primarily relies on rapid changes on the economy's supply side. A rapid increase in energy efficiency at the end-use (for example, by insulating buildings) must go hand in hand with the electrification of energy demand based largely on renewable sources. Households and the economy should hardly notice any difference; only the energy-intensive industry, which transitions as much as possible to renewable energy and 'net zero' technologies, will undergo significant changes according to this plan. Several assumptions of this plan are unrealistic. For instance, the EC emphasizes in its communication that new technologies, such as hydrogen production by electrolysis and carbon capture in the industry, are crucial parts of the energy transition between 2030 and 2040. Although technological developments are on their way, hydrogen and carbon capture are currently not ready for use, not easy to scale and at least never employed at a scale needed for the net-zero strategy, so relying on them is speculative. In addition, even when it would be technically feasible to capture (non-abatable) carbon emissions and replace fossil for renewable energy generation, getting all the materials needed for that transition would be challenging.

Furthermore, the assumption is that a supply-side energy transition will have limited effects on overall economic activity and private consumption is also expected to be minimally affected. The assumption is that there is little friction in shifting workers and capital between sectors; we will not phase out usable machinery but only redirect new investments towards a more sustainable direction. Workers can also easily find employment in other sectors.

The most unrealistic aspect of this plan is the almost complete lack of a vision for the transition on the demand side of the economy. It is striking that the EC does not mention behavioural change and demand reduction as one of the central policy options in its plan. The advisory report instead pointed to a scenario with low energy demand as the safest, most realistic, and with the most additional benefits. Transition science also teaches us that making a fundamentally unsustainable socio-technical system sustainable requires more than incremental (technological) improvements such as solar panels and carbon filters. Although solar panels and carbon filters are essential, they ultimately address symptoms in a fundamentally unsustainable system. A shift to a different socio-technical system is necessary, and policy on the demand side of the economy can contribute to this. Support for policy targeting the demand side of the economy is high among citizens. The willingness to sacrifice income for climate action is high worldwide according to recent research.

Most European participants in this survey also believe that governments should do more to combat climate change. Despite demand reduction and behavioural change hardly playing a role in the EC's proposal, there is still some reliance on demand shifting in the plan. The EC expects the total energy demand in 2040 to be somewhat lower than it is now. They also expect consumer prices to be lower. They seem to discount rebound effects here. Rebound effects occur when demand increases due to something becoming cheaper or more efficient. Rebound effects are often observed, for example, in the increasing size of electric cars now that batteries are more efficient. These rebound effects can (partially) nullify the 'gains'. Rebound effects are not a problem; they are part of market dynamics. It becomes problematic when a rebound effect undermines the original goal, as is the case with reducing greenhouse gas emissions or energy demand.

In the energy transition, the EC should pursue several goals. As the previously mentioned figures on the fair carbon budget for the EU show, greenhouse gas emissions must decrease as quickly as possible. This means phasing out all fossil energy sources within technical possibilities. This argues for a substantial reduction in energy demand for two reasons, at least in the short term. Firstly, renewable energy requires scarce resources, such as copper. In addition to how we can ensure that enough resources are available and limit geopolitical risks, there is also a justice argument here. The more we buy these resources, the harder it is for other countries to transition to renewable energy. Secondly, the power grid is currently overloaded in several countries. A quick transition to sustainable energy sources requires a renovation of the power grid, for which the EC also has a plan. However, the power grid's capacity is currently in some countries, like the Netherlands, a limiting factor. Rapid decarbonization of the energy supply is, therefore, practically difficult to implement. Demand reduction is therefore logical from a fairness perspective and from the goal itself (reducing total emissions). Practically, demand reduction is the best way to reduce energy-related emissions with a full power grid quickly.

We know that a declining energy price - as outlined in the EC's plans - will actually strengthen energy demand. If we want to reduce energy demand rapidly, additional policy is needed. This policy can roughly be based on two principles: market principles and social principles. Policy based on market principles is widely used, for example, in the European emissions trading system. The underlying assumption of a system with freely tradable rights is that an economically efficient distribution of emission rights is also socially optimal. After all, the highest bidder expects to achieve the highest financial return by purchasing the emissions unit. Financial value expresses individual preferences, so more money means more preference. This is socially optimal if your social utility function is a simple sum of individual preferences, regardless of distribution.

In practice, distribution is indeed a part of the social utility function experienced by many of us. Perhaps freely tradable rights would work in a society with hardly any income or wealth differences, but given the unequal distribution of resources, the distribution of a scarce and basic good like energy through markets does not lead to an outcome perceived as socially optimal. This was reflected, for example, in the policy surrounding rising gas prices in the winter of 2022-2023. We prioritized household consumption by imposing a price ceiling for small consumption, while we urged large consumers to save as much gas as possible and accepted that certain large consumers had to shut down production completely due to high prices. Here, the importance of distribution in our social utility function - we value more that people can heat their homes than that the highest bidder uses gas - became visible in practice. If we want to reduce energy demand rapidly, a trading system will again not lead to socially optimal distribution, so a policy focused on specific forms of energy demand is necessary. Therefore, we need a policy aimed at rapidly reducing energy demand to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Since the distribution of scarcity via energy markets does not lead to socially optimal outcomes, we need a policy focused on specific forms of energy use.

Although not mentioned in the EC's plans, some national policy measures are already in this direction. The energy-saving obligation for large consumers in the Netherlands is a good example; all companies with high electricity or gas consumption must take energy-saving measures if they are reasonably affordable. Exactly this kind of policy can ensure that demand quickly decreases. Unfortunately, this obligation is currently poorly enforced.

Steering on energy demand can be much more targeted than simply forcing large consumers to become more energy-efficient. Some forms of consumption are ecologically very burdensome and may need to be discouraged with robust policy measures. The previously mentioned increasingly large electric cars are a good example of this. They consume more energy and critical resources than smaller variants. Discouraging SUV use, for example, by tripling parking fees, as the city of Paris plans to do, could help reduce emissions. Elevating such initiatives to a European level would aid in emission reduction. Also, a progressive aviation tax – especially for private planes – does not compromise livelihood security but does lead to less demand for greenhouse gas-intensive products. In general, limiting overconsumption of energy-intensive and hardly welfare-enhancing consumption, from fast fashion to (excessive) meat consumption, can contribute to achieving emission targets. Instead of tinkering with specific forms of end consumption, a more equal distribution of income and wealth can also result in lower emissions, as the wealthy are responsible for a particularly large share of global emissions. Although less targeted than, for example, an aviation tax, reducing inequality through wealth and profit taxation could significantly reduce forms of excessive consumption and generate tax revenues that could be used to invest in sustainability and public services.

Transitions only succeed if they are inclusive in the short term

It may seem strange to call for a higher level of ambition and plans that intervene on the demand side of the economy in a time of increasing populism by climate skeptics and widespread farmer protests. However, in our view, the lack of demand transition in the EU's plans is one of the two reasons that setting goals for the agricultural sector is problematic. Without addressing the demand transition required in agriculture, a realistic transition plan is hardly feasible. Secondly, a prerequisite for a transition plan is perspective for farmers, which is currently largely absent.

The demand transition looming over the agricultural sector involves a shift towards a diet with significantly fewer animal products, particularly red meat, and more plant-based food. As long as we do not address this, we will continue to be stuck in the observation that emission reduction in this sector is 'very difficult'. Reducing meat consumption also has additional benefits; for instance, a 'planetary health diet' is healthier for humans and reduces demand for items such as animal feed, one of the driving forces behind deforestation in the Amazon. It would be desirable if the EC sets a goal for the next 10 years that meat consumption and production in the EU must decrease significantly, and links this to transition arrangements that provide farmers with income security in the transition to organic, plant-based agriculture. This short-term livelihood security (or inclusive transition) is not only necessary for livestock farmers; social tenants in poorly insulated homes or miners facing job loss should also know that their livelihood security is assured in the transition process.

Conclusion

Given the limited carbon space and our international responsibility, the current plans of the EC are inadequate. By focusing solely on the supply side of the economy and relying on unproven technologies, it is not very credible that we will even achieve these goals. The promise not to change the system further seems to be the only method to give people the idea of livelihood security, but in the longer term, it begs for trouble. After all, if the goals are not met, not only will valuable time be lost, but the political problems will only grow; the promised livelihood security turns out to be absent in the future.

The only real and sustainable direction for successful emission reduction and livelihood security is to acknowledge that we also need to address the demand side of the economy. By clearly conveying this message and offering a clear transition perspective, we can start this transition based on trust. This way, the EU will truly become an international leader in climate action.