#39 The end of neoliberalism and other assorted love songs

...and other reimagining

Hi all,

Let’s begin this blog with music. A long time ago (in the eighties), I collected all the records from Eric Clapton (yes, old man). The records I liked most were the old ones (also when I collected them): Derek & the Dominoes, Cream, and Blind Faith. Especially the 1970 Album Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs is one of my favourites (if you don’t know it: here on Spotify). In 1970, Eric Clapton poured his anguish into this concept album steeped in emotional turbulence. The centrepiece, "Layla," tells the story of an unattainable love—Clapton’s obsession with Pattie Boyd, the wife of his friend George Harrison, guitarist from the Beatles. Inspired by the Persian legend of Majnun and Layla, the song captures an arc of longing, rapture, and collapse.

The song begins with a feverish intensity, symbolising the initial thrill of desire. But as it moves into its iconic piano coda, written by drummer Jim Gordon, it shifts into something more mournful, reflective, and broken. It seems that love can promise the world, yet deliver heartbreak.

This same arc—desire, disillusionment, and breakdown—can be used to trace the rise and fall of neoliberalism, the dominant political-economic ideology of the last half-century. Neoliberalism emerged in the late 1970s and gained dominance in the 1980s as a response to the perceived failures of Keynesianism. It promised a renaissance of freedom and prosperity, grounded in the belief that free markets, deregulated industries, and a minimal state would generate wealth, innovation, and efficiency. Politicians like Margaret Thatcher, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair championed these ideas, embedding them in policy and popular imagination. It became an obsession (just like Clapton…). The private sector was lionised; the public sector demonised. "There is no alternative," Thatcher famously declared.1 The market was not just a mechanism for exchange—it became a moral force, a disciplining logic that would supposedly reward merit and punish inefficiency.

Neoliberalism, defined across Scott (2023) and Firth (2024), emerges less as a coherent economic doctrine and more as a hegemonic and moral order. This doxa subtly permeates institutional and everyday life under the guise of non-ideological "common sense." Drawing on Bourdieu and Lacan, Scott illustrates how economics, as a field, has naturalised neoliberal norms through a technocratic, positivist epistemology that obscures its ideological underpinnings. This invisibility is sustained by the refusal of economists to identify with neoliberalism, its erasure from mainstream economic discourse, and its recasting as objective truth rather than as contested political terrain. Neoliberalism fuses market logic with identity politics and traditional moral values, producing what [Brown] calls a "Frankenstein's monster" of moralised market reason that discredits social justice while fueling anti-democratic populisms.

Hence, the promises of neoliberalism proved seductive rather than sustainable. Free trade was hailed as a pathway to global equality, yet it often deepened economic dependence and extractivism in the Global South while hollowing out industrial bases in the North. In reality, the notion that prosperity would “trickle down” from the rich to the poor was never borne out. Instead, wealth accumulated upward, leading to levels of inequality not seen since the Gilded Age. While productivity and GDP rose, income for the bottom half of the population stagnated or declined. Even in wealthy nations, the social contract began to unravel.

What was marketed as “free competition” often led to monopolisation. In sectors like technology, media, and pharmaceuticals, a handful of dominant players now dictate terms to governments and consumers alike. Public goods were privatised—schools, healthcare, water, energy—often with declining service and rising costs. Gig economies replaced job security with precarity. Meanwhile, climate change worsened, framed as an “externality” beyond the remit of economic models. Environmental degradation became collateral damage in the race for growth.

I am repeating myself.

The dissonance between promise and outcome grew harder to ignore. Financial crises, soaring housing prices, degraded labour protections, and mass disenchantment began to signal a declining system. The 2008 global financial meltdown marked a turning point, revealing that neoliberalism’s internal contradictions were not minor glitches but structural flaws. Rescue packages were doled out to banks and corporations, not to workers or renters. The illusion of meritocracy was shattered.

Today, neoliberalism's ideological scaffolding collapses in real time, completely aligned with Fraser's analysis. The complex fusion of neoliberalism ultimately undermines democracy, corrodes social cohesion, and fails to deliver equitable prosperity—yet persists partly due to a lack of compelling counter-narratives. People have voted massively for change, but voted for a change that is not in their interest, and certainly not in the interest of their children.

Fraser calls for a new progressive-populist bloc that re-integrates redistributive justice with inclusive recognition as neoliberal hegemony unravels. At the same time, Brown urges rethinking values and subjectivity beyond neoliberal moral economism. Both signal that what comes next must attend not just to new policies, but to the reconstitution of meaning, belonging, and the ethical foundations of the social order.

Currently, where we are is not a vacuum where we can think freely about what should come next. We witness a descent into new forms of dystopia. Authoritarian populists like Trump, Orban, Modi, and Wilders have capitalised on the cultural and economic dislocation that neoliberalism engendered. The sense of belonging and security once promised by a social welfare state has been replaced by a politics of resentment, nostalgia, and exclusion. Machismo and nihilism thrive where solidarity has receded. Demagogues, decades of corporate lobbying, and judicial capture erode the rule of law. In Gaza, a genocide unfolds with chilling impunity, and the international order looks away—paralysed, complicit, or indifferent. If you are an autocrat, oligarch or post-neoliberal at least less-democratic government, why should you care?

This is not simply a moment of chaos or mismanagement; it is the end of a paradigm. We live through the death spiral of an economic and moral worldview. The market fundamentalism that once commanded reverence is now met with scepticism, if not outright contempt. From the rollback of environmental protections to the criminalisation of protest, what is being normalised is not a deviation from liberal norms, but the exposure of their limits. The dystopia unfolding is not an accidental byproduct but the logical end of a system that treated growth as sacrosanct and equity as expendable.

Yet in this collapse lies a strange kind of hope. If dystopia is politically possible, then so too is utopia. Ideas once dismissed as utopian fantasy are now entering mainstream debate: universal basic income, decommodified housing, guaranteed healthcare, democratic control of energy and infrastructure, and economies structured around wellbeing rather than GDP. These are not theoretical constructs. They are being trialled in real places, by real communities. What is needed is not more innovation, but commitment to already existing ideas—rooting them in everyday practice and making them politically contagious. One of my radical, hopeful thoughts is that limits and sufficiency can be normalised, just like the idea of never-ending growth and maximising is now the norm. See below for more on these other assorted love songs.

The challenge, then, is narrative. Just as Layla moves from fury to fragility, from electric guitar to echoing piano, our political movements must learn to shift from critique to composition. We must write new social arrangements into being—through organizing, imagination, and repetition. We need stories that people can believe in, not because they are simple, but because they are true to human dignity.

Clapton’s Layla was born from a deep personal crisis. But in that grief was the seed of renewal, of truth-telling. Our global crisis is no less emotional. It is marked by heartbreak, betrayal, and yearning. But like any good music, it also contains the possibility of transformation. We cannot return to the false certainties of the past. But we can write a new score that dares to turn longing into vision and despair into resolve. Therefore, we continue with some other assorted love songs.

Other assorted love songs

As always, I split my blog into the Newsletter (the part above) and some deeper stuff, mostly based on recent papers. Also, this time, I think these papers give some direction on the other assorted love songs we need or the (radical) alternatives we seek. Or: From TINA to TAPAS (plenty of other options).

So, my love songs are about flourishing. Limits to efficiency, banning advertisement, and Post-growth business. I love it! Self-restrictions, regulatory restrictions, prohibitions, restrictions in company size, income, wealth, and other things that are not aligned with neoclassical economic thinking. As is Trumpian Nepotism.

#1 Flourishing

If neoliberalism was our Layla, desperately desired, frantically pursued, and finally disillusioning, perhaps "flourishing" is one of the other assorted love songs. Less intense, less blinding, but more sustaining. In the aftermath of neoliberal collapse, we need not just critique; we need a reorientation toward what makes life livable and good, not just survival, not just GDP, but flourishing.

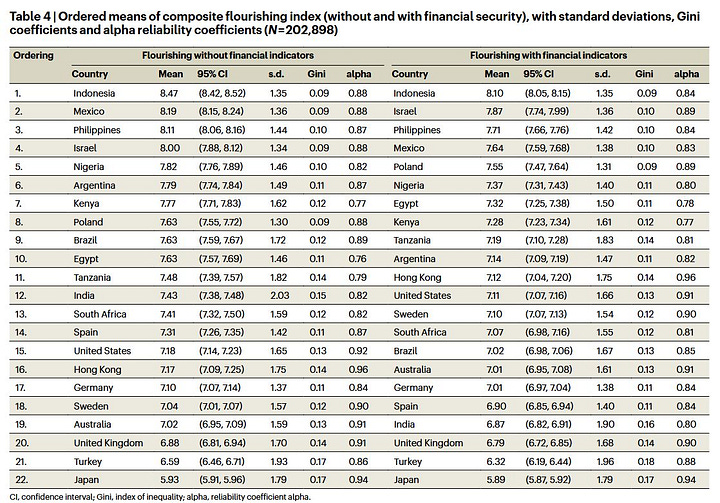

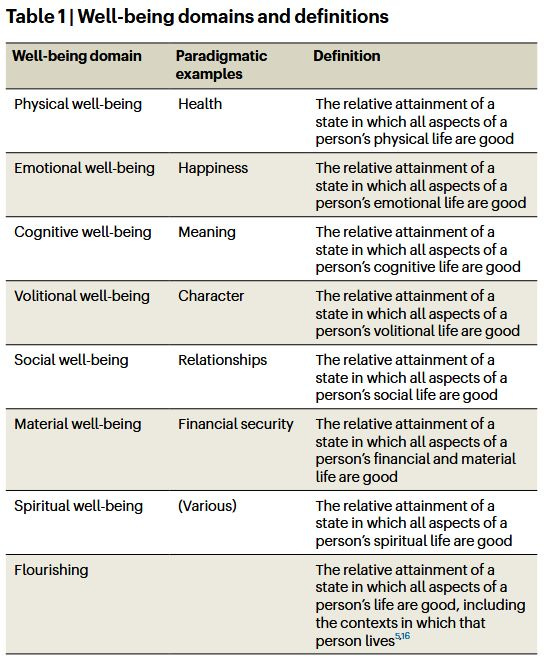

The recent Global Flourishing Study, spanning 22 countries and over 200,000 people, offers a new lens to understand what this might mean. It defines flourishing as the relative attainment of a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good, including the contexts in which they live (see below for definitions and scoring). This is crucial. Flourishing isn’t a self-help project. It’s not about optimising your life in a vacuum. It’s about whether your society allows you to grow, connect, and contribute meaningfully.

Countries like Indonesia, Mexico, and the Philippines report the highest levels of flourishing, while wealthy nations such as Japan, Turkey, and the UK fall to the bottom. Flourishing, it turns out, increases with age. At the same time, young people today report alarming deficits in meaning and purpose—a sign, perhaps, of how corrosive contemporary life has become for those coming of age in its midst. The study finds that what matters most for adult flourishing isn’t wealth or prestige but the quality of one’s early relationships, health, and spiritual or communal ties. Close parental bonds, weekly participation in religious or community life, and a strong sense of belonging are potent predictors of well-being. Conversely, childhood adversity—abuse, neglect, or social exclusion—casts a long shadow, diminishing a person's chance to thrive decades later. These findings challenge the myth that well-being is a private affair or purely economic. They invite us to rebuild a social and political architecture in which flourishing is a shared horizon, not a solitary climb.

Neoliberalism never made room for this. It defined success as individual, measurable, and monetised. You bought, competed for, or unlocked well-being through entrepreneurial grit. But the study tells a different story. Flourishing is distributed unevenly. It is shaped not just by choices, but by childhood conditions, relationships, social cohesion, and even the frequency of religious or communal engagement. It echoes what many have felt intuitively: that our capacity to thrive is bound up with the quality of our bonds, our health, our sense of purpose—and yes, our material security.

This is a sharp break from the worldview we were sold. Under neoliberalism, flourishing was privatised, and the state's role was to retreat. But what we see now—empirically and ethically—is the urgent need for public commitment to collective well-being. From physical and emotional health to meaningful work, stable relationships, and basic financial security, flourishing is a systemic achievement, not a personal hustle.

Perhaps the real revolution begins when we stop trying to fix the broken melody of Layla and begin to write new songs—more honest, more whole. Love songs, yes, but not for myths of markets or messianic growth. Love songs for thriving communities, for environments that heal, for lives lived with dignity. Neoliberalism ends not in rupture, but in quiet recognition: the dream it sold us was always too narrow. Flourishing reminds us that another dream is possible—and already unfolding.

#2 Rebound: Another Love Song in the Circular Afterlife

This is the love song of circularity: elegant in theory, appealing to the eco-conscious imagination, yet shadowed by complexity and debunked by reality. If flourishing were a tender ballad to well-being, the rebound is the lament that follows our obsession with efficiency. This article is evident and excellent in its comments.

The circular economy promises to close loops, reduce waste, and make consumption cleaner, leaner, and greener. Yet, as the authors argue, this narrative has a dangerous blind spot. Efficiency, it turns out, can be an illusion. What appears to be progress—repair cafes, sharing platforms, rental models—can backfire as I also argued in my previous blog. A repaired phone becomes a secondary device, not a replacement. A shared car saves money, which is then spent on another flight. The rebound effect—where gains in efficiency lead to greater overall consumption—is not an economic fluke or a psychological quirk. It is a systemic feature of how we live.

This article’s brilliance lies in its invitation to rethink rebound not as a misbehaviour of individuals, but as an emergent property of social practices. Circularity isn’t just about what we do—it’s about how doing changes when infrastructures shift, meanings evolve, and practices recraft themselves in unexpected constellations. A faster shower becomes a longer one. A more efficient freezer invites bulk-buying and energy-hungry storage. The article dissects this beautifully: our rhythms of life, spatial routines, provisioning systems—all become agents in a drama of unintended consequence.

The great betrayal of neoliberalism was that it framed consumption as choice and change as innovation. But what this research reveals is deeper: consumption is structured. It is material, temporal, and spatial. It is not just what we buy but how we live. Ouch! We live the neoliberal collapse ourselves, not as spectators, but as actors. If circularity is to be more than greenwash, then it must be rooted in this complexity. It must reckon with rebound not as a footnote but as a central plot.

And yet, this is a love song—because there is something hopeful in the honesty. Just as Layla ends in the aching clarity of its piano coda, this analysis invites us to slow down, listen more carefully, and design not just products but patterns. A world that takes practice seriously stops asking how we can buy our way out of crisis and starts asking how we might live differently, together. It’s not as seductive as growth, perhaps. But in its humility lies the promise of something real.

#3 Keep on Growing: A Love Song for the Degrowth Business

If Layla was our fever dream and Bell Bottom Blues from the same album, our quiet confession, then Keep on Growing is the resilient ballad of transformation, less about heartbreak, more about what we do in its wake. There is something almost prophetic in the song's insistence: “Keep on growing, keep on growing, keep on growing.” Not in the GDP sense. Not in profit margins or quarterly gains. But in something older and deeper: growing in connection, care, and courage to break with a paradigm that no longer works. In this way, it becomes the soundtrack to a post-growth economic reimagination.

The recent article "Degrowth and Business: Towards a Holistic Research Agenda" sketches what this transformation could look like. It combines years of scattered, often marginalised research and organises it through a powerful new lens: the deep transformations theory. Rather than reduce degrowth to “less,” this theory weaves a dialectic of less and more—less exploitation, more empathy; less throughput, more sufficiency; less hierarchy, more cooperation. It treats transformation not as a checklist, but as a whole-system shift, encompassing how we engage with nature, each other, institutions, and our inner lives.

And business? Business is not excused from the stage. It is reimagined entirely. The paper suggests that a degrowth business is not simply about smaller scale or local production (though it includes these). It is about altering the very telos of business—moving from profit maximisation to care, from competition to solidarity. It unfolds across four “planes of being”: in the materials we use and discard; in the way we work together and make decisions; in the social structures that enable or constrain change; and perhaps most radically, in our own interior worldviews. Moral growth, it argues, is part of the model.

What’s striking and gives this love song its hopeful tension is that the authors do not pretend we’re there yet. They insist that we must resist collapsing the present with the future. Today, most businesses operate within the growth economy, constrained by rent, debt, platform dependencies, and legacy systems. Even those striving for transformation are not pure. They are navigating what the authors call “system knowledge” (where we are), “transformation knowledge” (how we might change), and “target knowledge” (where we’re headed). The journey matters. The imperfection matters. Degrowth is not about purity—it’s about direction.

Keep on Growing wasn’t the hit single. It didn’t have the mythic status of Layla. But maybe that’s the point. In the wreckage of one story, another begins—not with fanfare, but with the quiet persistence of those who plant, tend, and trust that something different can take root. Degrowth business may not yet be centre stage. But it is writing new verses. It is rehearsing new harmonies. And it is doing so with a grounded realism that refuses both despair and delusion.

This, too, is a love song. One with calloused hands, collective ownership, and an eye on the long arc. The kind of song we need for a world that’s not just collapsing, but composting.

#4 Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out: The Love Song of Sufficiency

There’s a deep irony in how sufficiency has been treated in the modern policy songbook. Like Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out on the album, the blues refrain speaks of forgotten friends and discarded values—frugality, modesty, contentment—pushed aside by decades of economic dogma that glorified excess and consumption. Neoliberalism promised that more was always better. But now, in the face of planetary breakdown, we’re beginning to remember what we tried to forget: that there is wisdom, and even beauty, in knowing what is enough.

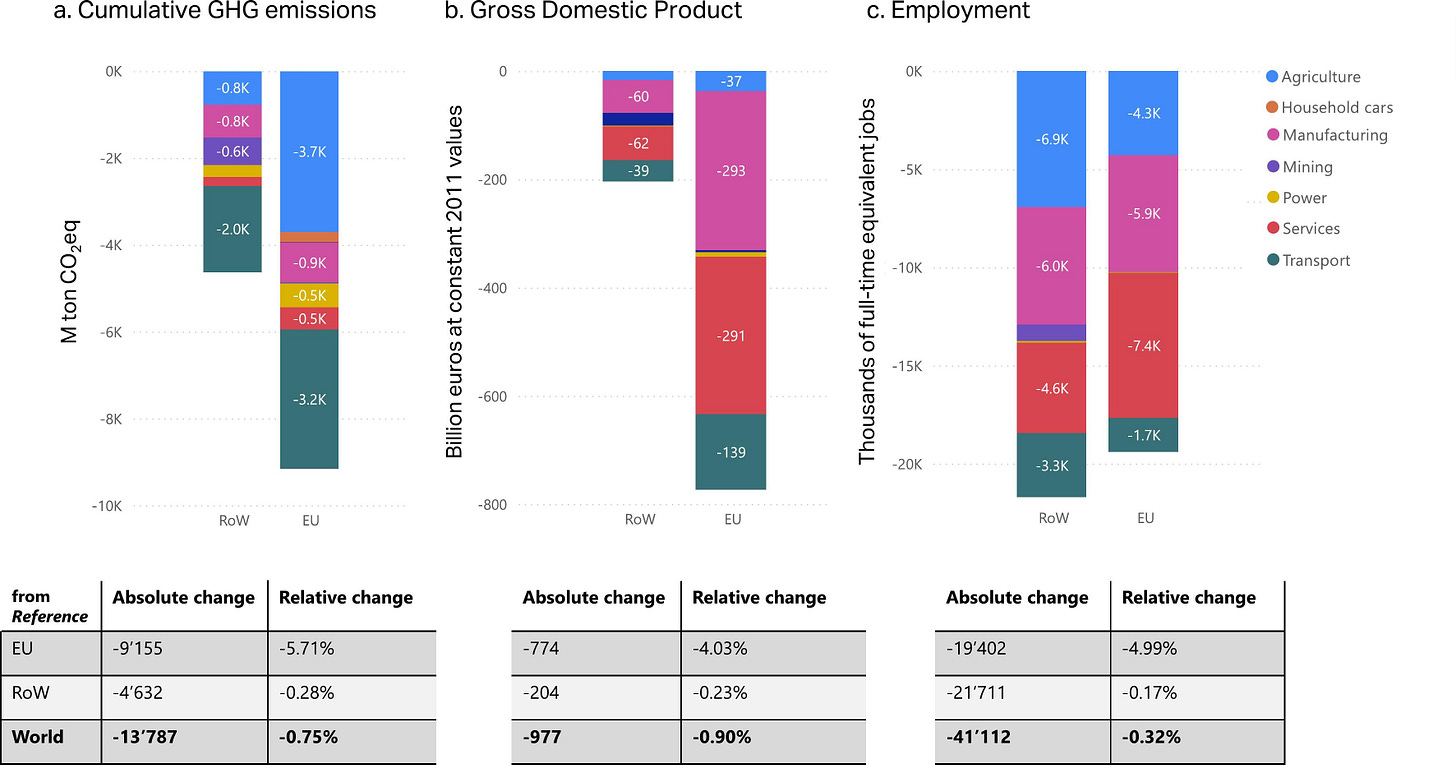

A recent study on sufficiency in Europe’s climate strategy gives this idea new force. Drawing from multi-regional input-output modelling, it shows how lifestyle changes—eating less meat, reducing flying, sharing goods and space, cycling more, and living in smaller homes—could cut the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions by up to 13% annually, saving nearly 14 gigatons of CO₂ by 2050. These are not fringe ideas. They are powerful, systemic levers that can complement technological solutions and even substitute for them in some domains.

And yet, as the song goes, when sufficiency was “down and out”—dwarfed by techno-optimism and green growth narratives—nobody wanted to know. Mainstream models fixated on electrification and efficiency. The lifestyle component was treated as soft, speculative, or moralistic. This study challenges that omission head-on. It quantifies sufficiency’s impact both environmentally, economically, and socially. Its findings are striking: while some measures like car downsizing have limited impact due to expected decarbonization of vehicles, others—especially dietary shifts and reduced air travel—deliver large, resilient cuts to emissions. Even more strikingly, these changes moderate GDP and employment, suggesting that sufficiency need not come at the expense of social wellbeing.

But sufficiency is more than a dataset. It’s a philosophy of restraint in a culture of speed. And this is where the second voice in this love song comes in: the emerging role of advertising bans. Another study examines whether restricting ads for harmful products can spur innovation in benign alternatives, much like banning beer ads in Norway, which led breweries to experiment with non-alcoholic variants, as this article has evidenced. The results are promising. Restrictions on the cultural promotion of excess consumption not only reduce demand; they may catalyse the emergence of new social norms and markets.

Think of it this way: sufficiency is the quiet melody, and advertising restrictions are the change in key. Together, they destabilise the dominant chord structure of consumer capitalism. They make space for a new refrain where possessions do not index dignity, and progress is not equated with throughput.

“Nobody knows you when you’re down and out.” But maybe that’s changing. Maybe sufficiency is the friend we’re learning to recognise again—not out of nostalgia, but necessity. And maybe we’ll look back and wonder why it took so long to hear its melody.

Another love: A Coda to the Assorted Love Songs

I think these are enough love songs for a week or two.

We've followed the arc—from Layla's burning ache through the tender hope of flourishing, the sobering dissonance of rebound, the defiant rhythm of degrowth, and the quiet rediscovery of sufficiency. Each one, in its way, has told a truth about the systems we’ve built and the futures we might still choose.

These were not just abstract meditations. They were grounded in data, practice, and lived experience, drawn from rigorous studies that challenge the idea that more is always better, that efficiency can substitute for justice, or that technological salvation is just around the corner. These songs were also love letters to alternative ways of organising our economies, our time, and our expectations of life itself.

But maybe the most enduring theme is this: we’ve been in love with the wrong woman. For decades, we idolised a vision—neoliberalism—that promised freedom but delivered precarity, promised choice but gave us algorithmic manipulation, promised prosperity but left us with ecological debt. Politicians across the spectrum, including many who called themselves socialists, fell for her charms. And like Clapton’s story, we chased this love even when it meant betraying what we once held sacred.

And yet, once the love is over, new loves might come.

That is the quiet power of this moment. We are not without direction. The data from the Global Flourishing Study, the sufficiency models for Europe, and the marketing regulations that open up space for truly benign innovation are not utopias. They are grounded blueprints for a life less frantic, less extractive, more anchored in care and reciprocity.

We needn’t idealise them. But we should attend to their rhythm. Because a post-neoliberal world will not emerge from one significant rupture, but from a thousand overlapping refrains: in policy, practice, and everyday decisions. A new love might not start with fireworks. It might begin with a different question:

What does it truly take for people and the planet to thrive?

So we close the record, not with a grand crescendo, but with the quiet confidence of a new note held just long enough to signal: this isn't the end. Just another love.

Take care!

Hans

As a wonkish sidenote, people always refer to this speech, where she articulates the neoliberal agenda. Things like: "We have to get our production and our earnings into balance. There's no easy popularity in what we are proposing but it is fundamentally sound. Yet I believe people accept there's no real alternative." Later in the speech, she returned to the theme: "What's the alternative? To go on as we were before? All that leads to is higher spending. And that means more taxes, more borrowing, higher interest rates more inflation, more unemployment."

However, she does not say literally “there is no alternative”.

This is probably the most thoughtful, complete and poetic ‘essay’ I’ve read about the current economic and political structure ALL YEAR. And this is not for having not read enough 😆

Thank you so much for this roundup on the underlying root causes but especially for delivering a positive alternative❣️Let’s go and FLOURISH. TOGETHER. ❤️🔥 I’m off now listening to the other assorted love songs. Goodbye, Leyla 😘

Thanks for this glimpse of hope...