#38 Frustrations and the case for a European future

...and hope and criticism

Hi all,

I just returned from Paris to visit the Changenow conference—a VERY BIG gathering of people who talk and change. I did a few panels and a presentation. Of course, it is nice to be amongst like-minded people. But at the same time, I always doubt how we can make the biggest difference—by talking to each other or by talking to others and showing how change can be made. Some discussions frustrated me. And I am terrible at hiding my mood when sitting in a panel (or somewhere else). The main thing is: even if we are working hard, with all our energy to do things right, it might turn out, on a system level, to be wrong. I know many entrepreneurs and businesses work on changing the world for the better. But the brutal reality is that it is not coming nearer. The truth is that some of our attempts completely failed. And it is okay to make mistakes, but some are very costly. And we ran out of time. I will explain two of these mistakes below.

Another important theme in Paris (and in the last few weeks) is the future of Europe. I already voiced my ideas about the Draghi report in an earlier blog. I wrote an essay (in Dutch) about that last month; in the newsletter, you’ll find the elaborated and slightly updated version (with some wonkish details). Yes, Europe should stand on its own feet. But not by becoming a bad copy of the US.

This time, there are no figures or many academic references. So, people who like that: maybe next time. I also know that some people stop reading after one figure. I hope you make it to the end!

Mistakes

First, about mistakes. I want to spotlight two major, and frankly, frustrating misconceptions (though there are many more). The first is the belief that progress will naturally follow if our businesses pioneer sustainable practices and that micro results add up to macro outcomes. Secondly, sustainability regulations have significantly accelerated our shift toward true sustainability.

Micro business vs macro outcomes

I deeply admire the entrepreneurs and businesses creating sustainable products, building networks like B-corps, and supporting movements such as networks for social enterprises, For Good Leaders, which I also met and engaged with in Paris. These grassroots efforts are vital, and connections between those changemakers are essential. They offer living examples of what the new economy could look like. But let's be clear: inspiring as they are, they are no guarantee of systemic success.

We must remain critical and curious. We need to test, evaluate, and learn from these initiatives—because even when something feels like a step in the right direction, its broader impact can fall short or even backfire when viewed from a systemic level.

Let’s take the example of circularity. More sustainable or circular products often do not replace non-sustainable products. This is known as the circular rebound effect: when circular solutions lower costs or ease guilt, leading to higher overall consumption. Take refurbished electronics, for example. Extending the life of smartphones through repair and resale is a smart, resource-efficient move. However, lower prices and green marketing can encourage more frequent upgrades, increasing the number of devices in circulation. Similarly, fashion brands that use recycled textiles often promote their products as sustainable, which may lead consumers to buy more clothes, not fewer. The environmental gains per product are real in both cases, but the total impact grows. Without policies or business models that tackle overconsumption and promote sufficiency, circularity risks fuelling the problems it aims to solve.

In addition to this, we have the problem of scale. Even if we don’t have the rebound effects, it might also be that the production of these sustainable companies does not fit within planetary boundaries or is unnecessary. This is a problematic message. We don’t know exactly what a ‘fair share’ is in terms of ecological boundaries for a company (see also this blog), so we can not draw any finite conclusions at a company level. However, we can understand the necessity of the products they produce. Maybe a straightforward example, but my house is stuffed with sustainable bottles (doppers and others) that I got as gifts. One or two would be enough. So, if transgressing planetary boundaries through too much production can not be attributed to an individual company, it is an emergent property of the system: it only exists on a macro level. Then, we can come to the paradoxical conclusion that we have too much unnecessary sustainable production, while we, on the other hand, might miss basic needs. Hence, my frustration is that we can never decouple the action of micro actors from macro outcomes. And yes, it is complex. But that is reality.

Useless regulation

Let’s discuss the regulation of sustainable finance in Europe. Over the past few years, we've made a herculean effort to disclose, classify, and measure sustainability in financial systems. However, despite this work, capital flows have not shifted decently. Why? The underlying theory of change—that transparency alone will drive all actors to make different choices—is simply not delivering. And there are at least three key reasons why.

First, the systems we’ve built for transparency are so complex that the average investor or client can’t make sense of them. That’s a win for industry lobbyists who prefer the status quo. Second, we started on the wrong side. Transparency around unsustainable activities could arguably have a more immediate impact. If more people realised the extent of ecosystem destruction, human rights violations, or animal suffering embedded in the average investment portfolio, behaviour might shift much more quickly.

But the third—and perhaps most fundamental—problem is that we’re pushing on a string. Only niche actors and frontrunners will take a different path as long as the game's core rules remain unchanged—return expectations, capital requirements, and the lack of pricing for externalities in the real economy. It’s a sobering realisation, but one we must face. What now passes for "sustainable finance" often involves managing material sustainability risks. And these risks matter to finance primarily for two reasons: the growing threat of physical climate impacts, and the fear that future regulation might devalue today’s assets, leaving them stranded on balance sheets.

Let’s be clear: I do not favour watering down all the regulations. But there is nothing against simplification. The best way to do that would be to start by regulating harmful finance.

Often, good intentions are not enough. While we think we are doing great, they might deliver even worse outcomes. I hope that many will reflect more on the system impact of their efforts (and don’t get frustrated).

Europe can stand on its own feet

After the Second World War, Europe entered its American era. Weakened and divided, it accepted America's leading role in exchange for security and economic support. The US transferred $13.3 billion to Western Europe ($133 billion in 2024 dollars).. The Marshall Plan was not just a reconstruction package—it was the foundation of a new world order in which the U.S. became the guardian of the free market, and Europe the loyal partner. NATO, the EU, and the entire post-war project were built on the assumption that the American umbrella would always remain open. Until 1989 to shield us from the Red threat, and afterward from every evil—from Saddam and Osama to Vladimir—emerging from the rest of the world. This security umbrella also served as an economic shield; the European economy could continue to grow comfortably on the rear rack of the United States, free-riding on defence spending from the US.

But now, America seems less interested in safeguarding Europe and its interests. Communism is dead, and autocracies and oligarchies are friends. It is withdrawing, seeking profitable trade partners elsewhere, and flirting with Europe’s competitors. And at a pace Europe did not anticipate, while war once again rages across the continent.

The reflex is anger: didn’t we have agreements? Didn’t we share ideals? But perhaps the better question is: why did we assume for so long that someone else would guard our interests?

Maybe now is the time to reconsider the European economy. Instead of blindly copying the American model of “more market, more power, more militarism,” Europe must rediscover its strength. Building a European narrative—a model that puts our democratic values, qualities, and economic interests at the centre—is crucial and possibly our only hope. Because the global order is shifting, and it is time for Europe to redefine its place. The hope is that Europe realizes that national interests, cultures, and traditions can only be safeguarded through proper cooperation—both within and beyond the continent.

A Major Shock - easily diagnosed

It is crystal clear in the accelerating stream of recent developments: Europe has work to do.

Much of the diagnoses of Mario Draghi’s report on Europe’s competitiveness, and the European Commission’s follow-up plans, such as the Competitiveness Compass and the Clean Industrial Deal, are relatively uncontested. Europe’s material prosperity has long been based on cheap, imported energy and raw materials, and the continent has benefited for decades from an increasingly open and expanding world economy. All of this under the free protection of the United States.

After Russia invaded Ukraine, the problem of energy dependence became all too clear. Energy-intensive industries now face a significant competitive disadvantage because energy prices remain structurally higher following the loss of Russian supplies. Gas prices are still twice as high as before the energy crisis, and significantly higher than in the U.S. These high prices can only be partially offset by energy imports from elsewhere. The shift to renewables is the most obvious, yet also the most arduous path.

In addition to a cheap energy shortage, Europe faces a resource challenge. The energy transition requires rare earth elements. But not only for that: if Europe is serious about advancing AI and innovation, it will need even more raw materials. Think lithium and cobalt for countless applications for batteries, nickel, tin, and copper. Add dozens of rare earths used in microchips, displays, and electronics. These are not readily available within Europe. If nothing is done, we will trade one dependency for another—energy for resources. Russia may become less relevant, but China is all the more relevant.

Meanwhile, the advantage Europe enjoyed for decades from growing global trade—especially beneficial for German exports—is running out, trade war or not. European products are becoming less unique, with China already taking the lead in electric vehicles. Europe’s lag in innovation—particularly in AI—doesn’t help. But even if we were competitive, global trade growth has already lost momentum. And with Trumpian disruptions, things are only likely to get worse.

The final shock might be the most profound: Europe must start protecting itself. The peace dividend, consumed so indulgently since the late 1980s, is spent. Trump views everything transactionally, including alliances. There are no historical bonds, only business, even war.

Pavlov Isn’t Working

Europe’s Pavlovian reaction to all these challenges suggests we want to resemble our old friend the US even more. We must grow more, be more productive, buy more weapons, give more space to the market, and reduce regulation. That’s the message behind almost all reports and recommendations. As European Commission Vice-President Teresa Ribera, responsible for the green transition and competitiveness, said in the Financial Times: ““We need to ensure that there’s a story of growth and prosperity.”

I understand why she says that. It’s the underlying narrative. Now that the U.S. security umbrella is being folded, this is perhaps the most enduring legacy of our Anglo-American century: market logic and growth thinking have seeped into the pores of European policymakers. It’s hard for them to see the world differently.

This goes back to the post-war recovery. Europe was rebuilt with extensive American financial support. But not only that. With the money came a bookkeeping system for the economy: the System of National Accounts. It was very useful—it let you track how much was produced, consumed, and how incomes evolved. The overarching indicator became Gross Domestic Product (GDP). During reconstruction, more GDP—more growth—was undeniably good. More houses, more food, more clothes—who could argue with that in times of scarcity?

But GDP's dominance persists. Draghi begins his report by observing that the main problem is Europe’s lower economic growth compared to the U.S.

Yet by now it’s broadly acknowledged that a happy continent depends on much more than growth. As I stated in my previous blog, while the U.S. economy had grown 47% more over the past 35 years than Europe’s, this was mainly due to population growth from migration. Adjusted per capita, the difference shrinks to 9%. And when we look at income distribution, the average European—and everyone earning less—is actually better off than in the U.S. The bottom 50% of the income distribution saw their incomes rise 19% more in Europe than in the U.S. In other words, the ultra-rich in the U.S. kept all the gains for themselves.

And it doesn’t stop at income. On other indicators—life expectancy, safety—Europe performs better, all while achieving this level of prosperity with just half the CO₂ emissions and water use.

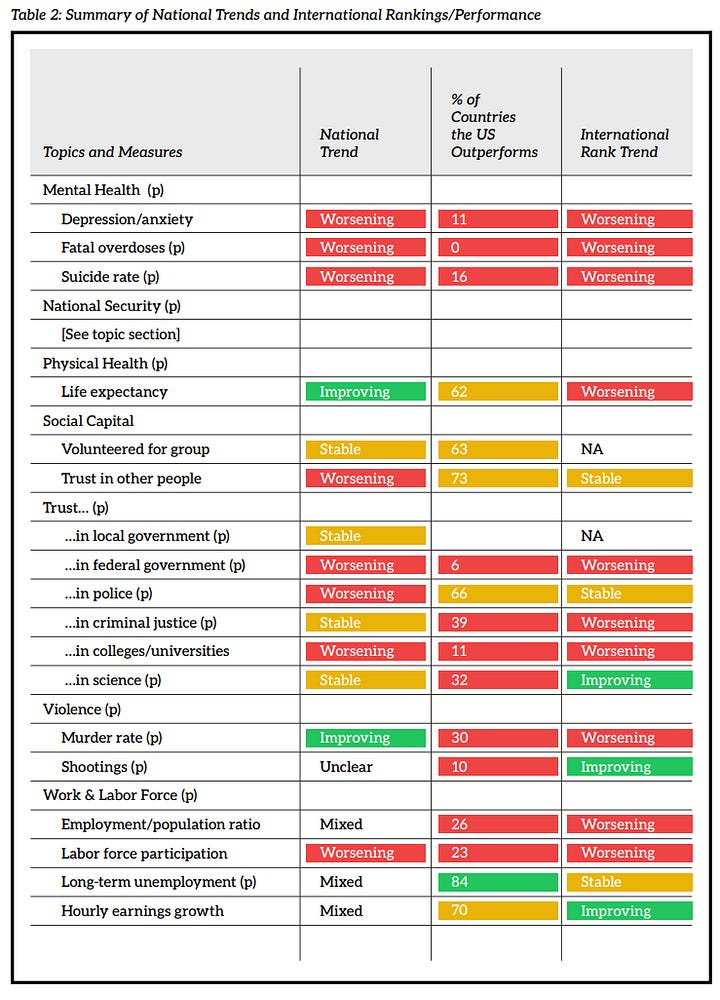

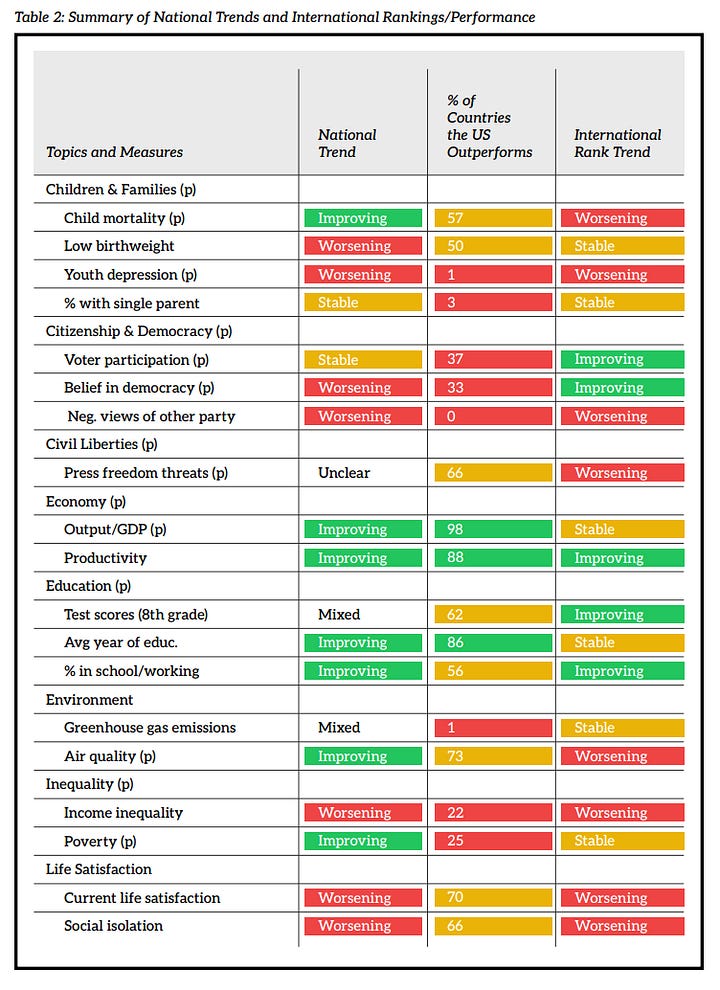

(US) Scientists summed it all up in this report. Check out the dashboard they created (see below). You’ll see that while economic growth and productivity metrics appear impressive, most other indicators tell a different story—lagging behind peer countries and, in many cases, deteriorating. The United States now has the lowest life expectancy of any wealthy nation, a striking reversal from much of the 20th century. It leads among wealthy countries in murder rates and has the highest rate of fatal drug overdoses in the world. Trust in the federal government remains extremely low, and youth depression and single-parent households are alarmingly common. Moreover, when Americans are asked about life satisfaction, the country ranks lower today than thirty years ago. The U.S. is so deeply unequal that average economic figures often fail to reflect the lived experience of most people—economic gains have disproportionately flowed to the wealthiest 10 per cent. The New York Times summarised the findings starkly: “The U.S. Economy Is Racing Ahead. Almost Everything Else Is Falling Behind.” Europe would do well to consider this when drawing comparisons. And it begs the question: does anyone still genuinely believe that economic growth is inherently tied to human well-being? The United States, one of the richest nations on Earth, is unravelling under the weight of an over-financialised, extractive, and individualistic obsession with endless growth.

Still, despite acknowledging these findings and differences between material growth and wellbeing, the only policy answer remains the American recipe: more growth, more of the same.

This illustrates another example of within-system thinking—specifically, the imperative for social or institutional growth. The narrative remains consistent: to sustain an inclusive, well-functioning society, we need continuous economic growth to fund pensions, healthcare, education, and other essential services. This logic holds within the current institutional framework. However, if growth slows—or if we come to see it as ecologically unsustainable and ultimately detrimental to well-being, especially in light of planetary boundary transgressions and the persistent lack of evidence for absolute decoupling of economic activity from ecological impact (beyond just carbon emissions)—then it becomes necessary to rethink our fiscal architecture. Our tax systems, heavily reliant on income, profit, and value-added taxes, are all predicated on economic expansion. A serious re-evaluation of these foundations could open the door to alternative fiscal models better suited to a post-growth or steady-state economy.

So, Europe’s answer should be much more nuanced. How can we use Europe’s strength and design policies that do justice to a European economy instead of becoming a neoliberal copy? That means focusing not on growth but on well-being.

European Strength

Focusing on well-being starts by making the European economy less fragmented. With 450 million consumers, Europe is a significant economic force. It’s also the most sustainable economy, not in how much energy and resources we consume, but in how efficiently we do it. We also ask more of businesses when it comes to responsible production. Lastly, Europe is innovative—maybe not in AI, but certainly in sectors like food, agriculture, and machinery.

If we leverage the strength of a united Europe, counterbalancing Russia (an economy the size of the Benelux) is well within reach. Spending 1.5% to 2% of GDP on defence should be more than enough.

But unlocking Europe’s power requires sacrifices—and even more, mutual trust. It demands that we organize and finance public goods—defense being the prime example—collectively. That’s a big step for Europe, but one more necessary than ever. Moreover, we could extend this to public transport, payments, and possibly even healthcare at the European level. It would be far more efficient. But it mustn’t become a neoliberal one-size-fits-all. We need to preserve space for cultural differences and diversity. Overreliance on efficiency and markets can also weaken an economy. As Europeans with shared goals, trusting one another is crucial for success.

A Non-Neoliberal Democracy

We can make other choices that take us further from, rather than closer to, the U.S. model.

First, growth must become less central. Counting on growth is futile if it is unlikely to materialise and if the difference between prosperity and growth remains so large.

Due to demographic shrinkage, Europe’s economy will grow more slowly in the coming decades. Fewer working people means a smaller economy. Innovation—the other growth engine—is hard to steer. Investing in preconditions for a strong economy is better: education, infrastructure, and research. This demographic fact and decades of slowing productivity growth should prompt smart policymakers to stop relying on growth—it only breeds disappointment. It should even lead to institutional reforms: making tax systems less dependent on growth-linked bases like profits, income, and turnover, and shifting toward taxing wealth and pollution and or limiting return expectations and societal debt.

Second, economic policy should not be driven solely from the supply side. The belief is that if sustainable energy, resources, and technology are available, everything else will follow. The energy transition is a clear example. There’s faith that more renewables and better storage will reduce dependence. But that becomes a huge task if we assume energy demand is fixed. We can (voluntarily) reduce demand as well. That’s possible, while remaining globally competitive, by encouraging alternative transport, improving homes (improving comfort), and reducing overconsumption. We should focus more on conscious energy use than trying to meet unlimited demand with green sources. The same applies to materials: recycling gets attention, reuse barely, and reduction hardly. Policies focused on sufficiency—having enough, not as much as possible—could be transformative.

Finally, there’s the myth that competition policy must always include deregulation. The EU has been dismantling sustainability laws—a mistake. The environmental problems won’t vanish. Companies may gain a short-term edge, but in the long run, Europe risks resembling the U.S., along with all its sustainability crises. Looser rules also delay the development of circular and energy-efficient industries. Strict sustainability rules are precisely what drive sustainable business models.

Persisting in a Different Answer

Learning to stand on our own feet as a European economy is possible. But it becomes easier if we unlearn our American reflexes. That means not defaulting to market solutions or repeating the growth mantra. We should collaborate where collaboration is essential—on defense, infrastructure, and basic services—and leave freedom where diversity can flourish.

It’s not easy—politically or economically. But if I had to place a bet, it would be on a serious attempt to make the European economy truly different—more inclusive, more sustainable, more competitive—by choosing a path that diverges from our American era.

It’s time for a European era for Europe.

Thanks all for reading.

Be nice,

Hans

And more equal, one might add!

Surely a new system, new thinking, and new ways of organizing democracies and cooperation with those that wish to work together is a better bet than the destructive ones right-wing extremists are promising, and that get votes because at least, they are "not more of the same".

But do our politicians know how to do sufficiency? Do our economists?

This (long) essay is quite instructive I think, hopefully in showing what we get to avoid: https://open.substack.com/pub/aurelien2022/p/the-end?r=ox5s5&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=false

... e.g. by following this movement-building outline from Naomi Klein and Astra Taylor: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2025/apr/13/end-times-fascism-far-right-trump-musk

This has been the most realistic article i have read so far!