#31 Tipping Points Investing

Looking differently at impact investing (or any investing)

Hi all,

The idea of tipping points is gaining more traction every day. For one, a tipping point is a way to express the speed and unexpectedness of nonlinear threats; for others, especially social tipping points, they are expressions of hope. Hopefully, even a critical minority can change norms and shift a system towards a more favourable state. Think about that as more sustainable behaviour, from eating less meat and flying less to car ownership.

This topic is undoubtedly relevant, though it challenges how we’re accustomed to thinking. We often rely on linear projections, extrapolating the past into the future without fully considering the intricate web of interconnections. Furthermore, the concept of tipping points might have been oversimplified or overstated in popular discourse. As Kopp et al. highlight in this recent article, what’s needed is a more nuanced understanding of tipping points. They emphasize the importance of viewing these as phenomena rooted in complex systems, where factors such as irreversibility, abruptness, self-amplification, potential surprises, and interlinkages within the system all come into play (see this related post for further discussion).

That said, tipping points remain a critical concept to address. Why? Because all systems—whether ecological, social, technological, or economic—behave nonlinearly and can shift between stable and unstable states. This aligns with ideas like Panarchy’s multistable equilibria (explored further here). However, I’ll resist the temptation to delve too deeply into the mechanics of complexity theory. I want to focus on a key point: nonlinear dynamics and tipping points are becoming increasingly relevant to anyone concerned with future developments.

One group, in particular, must pay attention to these dynamics: investors. They make judgments about the future. Everyday. This theme ties directly to our Investment Outlook, where space constraints didn’t allow a deeper dive into these crucial ideas.

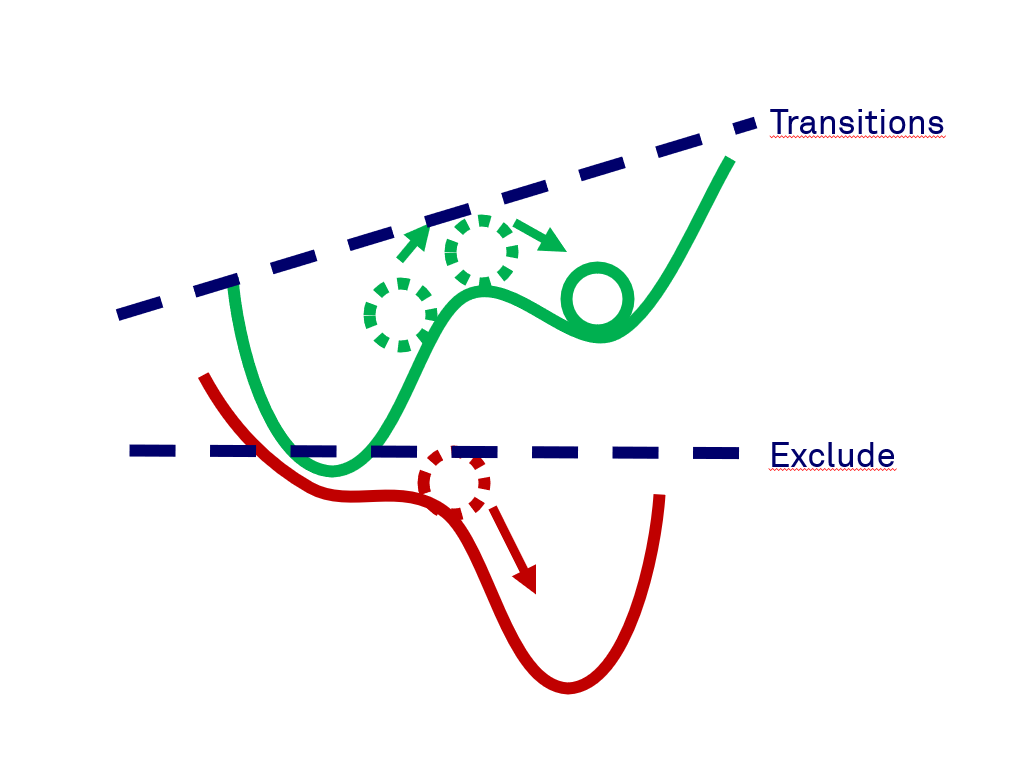

To understand Tipping Points, I created a small animation that explains stable and unstable systems, positive and negative tipping points, and nonlinear developments.

So, systems can have different states. But let’s assume (below you find more reasoning), that some of them are increasingly going in a negative direction (e.g. nature, social systems that seem to break down here and there). There are also upward, positive tipping points driven by technology, norm shifts, et cetera. What should you do then, as an investor?

It is not difficult, although it is completely different from what may investors do now. It takes two, very simple, steps for an individual investor perspective.1

The first step is addressing the significant risks of negative tipping points. How? Through deliberate exclusion. If you know that climate-related risks will materialize at some point in the future, take steps to mitigate them now. While it’s impossible to eliminate all physical risks, you can at least minimize transition risks. For those less familiar with finance, this means avoiding investments in areas like fossil fuels. Their end is inevitable, even if the exact timing is uncertain. The same principle applies to deforestation and other nature-related and social risks.

At this point, the seasoned sustainable finance professional might ask: isn’t this just ESG integration in portfolios? No, it’s fundamentally different for two key reasons:

The Precautionary Principle: Traditional ESG approaches often rely on quantifying risks, but when future risks are uncertain and potentially immense, you cannot afford to wait for precise measurements. Instead, adopt a precautionary stance: avoid these high-risk areas altogether.

Future-Focused Data: Instead of relying on ESG data based solely on a company’s past performance, we need forward-looking, outside-in ESG risk data that evaluates how companies will perform in the face of emerging challenges. This represents a significant shift in how risks are assessed and managed.

In short, addressing negative tipping points demands more than ESG integration—it requires a proactive, future-oriented approach to sustainable finance.

Second, on a more optimistic note, a nonlinear, forward-looking perspective is equally essential when considering positive tipping points. This idea isn’t entirely new—many investors already apply this approach to technological tipping points. However, things become significantly more challenging when it comes to social tipping points.

At Triodos Bank, we address this through a “transformative potential” approach (we’ve even published a paper on it). The transformative potential is an organization’s ability to actively contribute to deep and widespread systems change. It assesses how a company or initiative can play a meaningful role in driving transformation. Is this grounded in complex physics? Not. Like any investment strategy, it blends data, financial analysis, and informed assumptions about the future.

The challenge lies in how most investors continue to view the future as linear or exponential, often through a reductionist lens. We need a shift toward seeing the future as a complex adaptive landscape. This means evaluating a broader range of factors beyond financial metrics like revenue streams (which are hard to predict accurately anyway).

By embracing this complexity and looking at transformative potential, we open up new pathways for driving systemic positive change through investment.

It begins with a polycrisis, progresses through key tipping points, and concludes with actionable ideas. The challenges are significant, but it’s encouraging to know that there are steps we can take to make a difference.

If you’re not looking for more detail, feel free to stop here. The rest dives deeper into the specifics—but you’re welcome to read on if you’re curious!

Tipping Point Investing

We live in unprecedented times, where the future is more uncertain than ever. Nonlinear developments, complex interactions, and tipping points determine the investment horizon. To take advantage of this, we see combinations of resilience, transitions, and tipping points as the best long-term investment strategies.

Polycrisis and tipping points

The state of our world economy is incomparably different than at any time in history. Our Earth's environmental systems are dire; some are on the brink of collapse. In many societies, we face challenges of polarisation and fragmentation, leading to unstable governments. The global economic system is shifting from a neoliberal economic regime – one undermining itself through worsening instability, inequality, and ecospheric externalities – to a yet indeterminate regime, but one likely involving increased dirigisme and economic integration within ideological blocs. The international security system is changing from a world order based on American leadership (a ‘pax Americana’) toward an unknown, uncertain new state, where autocratic regimes, from Russia, China and India to Iran, Brazil and Indonesia seem to unite under the flag of BRICS2 as a force against the ‘old’ global governance as embedded in G7 and G20. The information system is being revolutionised by artificial intelligence, with unclear but likely unprecedented implications for employment, decision-making, and personal, national, and global security.

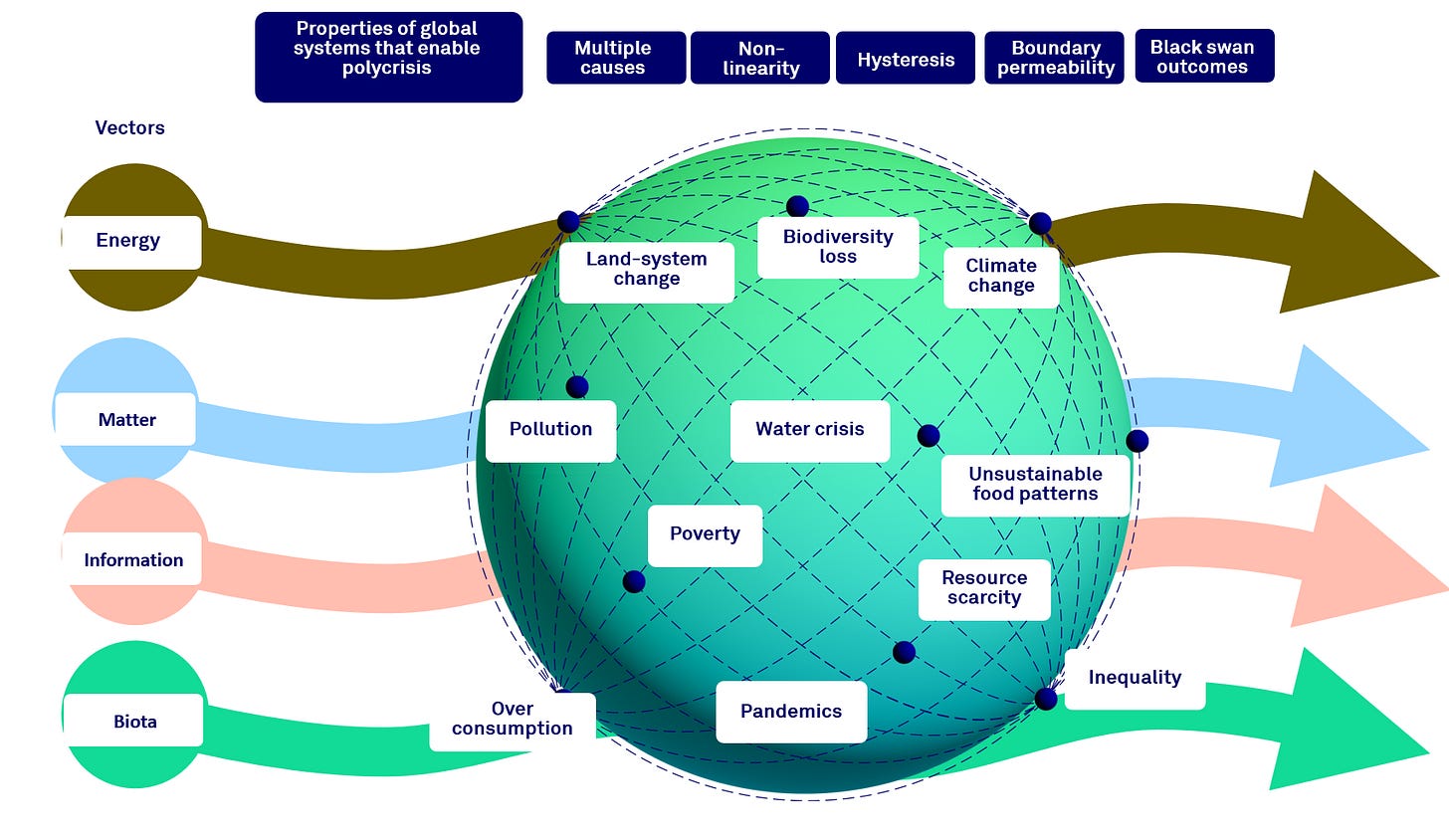

This situation, with many looming risks, can be called a polycrisis. This is "the causal entanglement of crises in multiple global systems in ways that significantly degrade humanity’s prospects”. The interconnectedness of various global systems exacerbates the negative impacts, surpassing the cumulative harm that would have arisen if the host systems were not profoundly entangled. Consequently, the confluence of these interacting crises significantly and irreversibly affects the economy and the financial system in unanticipated ways. What is different from (recent) history is (1) that the world is far more interconnected (hyperconnected) now than it was during the, for instance, the 1970s economic crisis, and (2) the world economy is more homogenised, i.e. through the pursuit of efficiency as a main evaluation criterion for economic activity and open access to markets while stripping away social and environmental safeguards there is less resilience of the system. In other words, we created a system more prone to a polycrisis. The carriers of the crisis are energy, biota (renewable resources), matter (non-renewable resources) and information (see figure). The properties of global systems that enable a polycrisis are multiple causes of crises, path dependence (hysteresis), boundary permeability (the extent to which a boundary (physical, social, or conceptual) allows interactions, exchanges, or movement across it), nonlinearity and black swan outcomes. Is it all bad? No. These elements (the carriers and the characteristics) also make it possible for positive effects – behavioural changes and technological progress – to be amplified faster and exponentially through the global economy. So, ‘green or pink swan’ outcomes are also possible (although even more unlikely). But the conclusion is the same: it is inherently uncertain.

A polycrisis environment makes it harder for investors to navigate in terms of developments and predictability. If you only do your bottom-up analysis, you miss the bigger picture; if you only do standard macro analysis and asset allocation, you dismiss and miss the most significant risks. So, it requires a more fundamental approach since one essential element of a polycrisis is the existence of tipping points.

The existence of tipping points in the development of ecosystems, social systems, and (hence) economic systems can irreversibly change a system into a better or worse state. Tipping points can make a good investment worthless—and vice versa.

This figure (the last slide of the animation) shows the notion of tipping points in a simplified version. A tipping point refers to a critical threshold, measured in terms of drivers external to the system, at which additional pressure causes a system to lose resilience and undergo self-propelling change into a qualitatively different state (see here). In standard investment analysis and economics, the assumption is like in panel (a): some ‘noise’ or uncertainty, but inherently an upward move, a positive development of the economic system or the investment. This is how economists make forecasts and analysts calculate the expected returns of an investment.

Given the polycrisis, it is better to expect non-linear changes. A system feature shifts if a system feature is moved or pushed through a specific driver. This can be an exogenous shock, such as forest flooding, a military coup in a country, or continuous pressure, such as global warming’s effect on rainforests. It can also be caused by endogenous dynamics, such as decreasing solidarity in a society or lower productivity growth than needed to keep the system stable. If the system develops as in panel (b), the internal or external forces push the system towards a better state. This can, for instance, be technology and innovation or changing social norms.

However, all systems (for instance, a forest or a society) can also be stable and resilient to change (panel (c)); all external pressures, either positive or negative, are not capable of changing the state of the system. This can be the case over long periods. But whenever we get to (d), the system's resilience is lost and destabilised. However, there is a possibility to go back to the old state. But if the system's resilience deteriorates further, we arrive at (e), where the system reaches a new (less favourable) stable state. This can happen when biodiversity collapses or when societies implode.

What is the problem?

Ecosystems have many tipping points that seem very close (see for instance here, here and here). If we overstretch the burden on ecosystems, we likely enter a different state (some people will call it collapse). This has two possible consequences. First, it will directly affect economic activity if it leads to natural disasters, ranging from extreme weather conditions to the collapse of (local) natural ecosystems. Second, it could imply that the services that nature delivers to the economy will disappear. This can also have severe consequences for economic activity since, according to the latest estimates, 55% of all economic activity depends on nature. The many studies on the effects of climate change show that the economic consequences are expected to be negative, more negative than earlier assumed, highly uncertain, skewed towards negative surprises and that poor countries are more vulnerable than richer ones. With 2024 being probably the first year above 1.5 degrees Celsius warming against preindustrial levels3[2] , we see what looks alarmingly like climate flickering [11]: the ever-wilder perturbations that tend to precede the collapse of a complex system. Hence, negative ecosystem tipping points are near, and policies to combat that seem far away. This will affect economies and investments.

The same accounts for other parts of the polycrisis. Inclusive and stable institutions and social capital are essential for the (well-being) performance of societies. This year's Nobel Prize for Economics was awarded for research, especially on this topic. However, there is also evidence that social capital erodes in many Western countries. At the same time, it is also clear that social capital plays a role in both micro- and macroeconomic prosperity, such as trust and solidarity and quality of institutions. Also, for social capital, there is evidence of tipping points, which are foremost framed as positive but can also be negative.

What is the upside?

Of course, this raises the question of whether all is negative. It is not. Technological tipping points are famous. When, at some point in time, technology reaches a certain maturity and turns out to be better than some other, older alternative, it can grow exponentially. And even more so, technological tipping points can sometimes solve ecological challenges. Take, for example, the energy transition. We can create a fossil-free economy through new technologies such as renewable energy, electrification of transport, and battery storage. Positive tipping points and non-linear developments are almost the same as the creative destruction of Joseph Schumpeter. For investors, it means betting on the right technology to be ‘the next thing’.

But this is not only a technological question. Successful technologies also depend on social adaptation. These (technologically induced) social tipping points can amplify positive changes. Consciously investing in different transitions can help investors (1) invest in the upside of a solution and (2) be resilient against negative shocks. For example, investing in companies that do not depend on fossil fuels implies that they are not exposed to more regulation on the phasing out of fossil fuels (transition risks), while they are part of a growing market.

The same holds for social tipping points. Social Tipping Points are crucial leverage points where small changes can lead to significant shifts in societal behaviours, norms, and policies towards, for instance, decarbonisation. These points are driven by positive feedback loops that amplify initial changes, propelling the system towards a new state. However, the inherent complexity of social systems means that these feedback loops are not isolated—they are interrelated with other developments, creating a web of interactions that can be difficult to untangle. Positive feedback loops, while powerful, are often accompanied by negative loops that can dampen or counteract the intended effects. For instance, efforts to shift public opinion towards anti-fossil-fuel norms may be met with resistance from entrenched interests and polarised views, creating a balancing act between progress and pushback. This interplay of reinforcing and counteracting mechanisms adds layers of unpredictability to social tipping processes. However, norm shifts can happen when a substantial minority starts to behave and think differently.

The investor perspective: reduce the biggest negative tipping points, invest in opportunities

Investors are used to thinking in terms of pretty linear developments. However, this is often not the case, as we see more and more in times of polycrisis.

What should be the lessons for investors? We think two things are essential: a better understanding the risks of negative tipping points and looking for long-term positive tipping points.

Risks for investors have changed over time. Taking a longer-run perspective, based on the Global Risk Reports (see this post about World Economic Forum Risk Report), it is clear that risks for the global community have shifted (see figure X). Economic risks dominated in the 00s; currently, environmental risks dominate. Twenty years ago, managing risks from within the system was relatively easy. You could assert that the economic system itself was not at risk; it was foremost managing the negative consequences of it. This is impossible to state now. Risk management is about ecological and social risks, such as polycrisis risks. A way to do that is by excluding the largest (unsustainable) ecosystem dependencies in portfolios, such as deforestation, unsustainable mining practices, pollution, human rights issues, et cetera. Is this ESG risk mitigation? Yes, it is. But not as a choice but as a necessity to avoid negative portfolio tipping points.

Second, the upside also has a different connotation. Of course, scanning for possible innovations or technologies that are investable is not new. However, the systemic nature of polycrisis also makes the upside even more unpredictable. So, understanding long-term transitions and looking for investable areas is a logical approach to achieving the upside. But how to make that practical? First, it starts with investors having a vision of where a transition should go and what technologies, companies, and initiatives can accelerate it. Second, a targeted approach on different leverage points can make a difference: analysing those investment opportunities that contribute most with the best possible risk-return profile and excluding exposure to negative tipping points.

The figure below summarises this approach: excluding negative tipping points where they affect individual investments the most, including positive tipping points in transitions.

Conclusion

I you take a holistic view on your investment future, this is kind of straightforward. As a matter of fact, this resembles (or close to) the investment approach of Triodos Investment Management. While we closely analyse the economic outlook for 2025, as long-term impact investors, we focus on the broader landscape of risks and opportunities. Increasingly, these risks and opportunities are systemic, global, and unpredictable. We believe in a “tipping point approach” to investing. This strategy enables us to identify the best long-term investment opportunities that can drive societal transformation—our way of helping to prevent society from reaching critical negative tipping points. Of course, no investor can shield himself or herself from all systemic risks. But by taking this approach, we do the best we can, not only to reduce risks but also to work on solutions.

That’s all.

Take care,

Hans

To be clear, this is the step to take for material negative tipping points that affect the (financial) performance of an investment (outside in). That is (of course) different from the effect an investment has on nonlinear developments (inside-out). In the second step this will be addressed (simply ensure that you do not aggravate negative nonlinear developments).

https://brics-russia2024.ru/en/