Hi all,

First and foremost, I wish you all a Happy New Year. May this year be a turning point for climate policy, encouraging regenerative investments and fostering just transitions. Above all, I hope voters recognize the necessity for a radical, progressive shift instead of leaning towards a conservative, populist backlash. Although I have concerns about the voting outcomes, I sincerely hope my apprehensions prove unfounded.

Welcome to the second edition of Tipping Point Economics, marking the commencement of the new year. As everyone eagerly anticipates what the year holds, this newsletter delves into the art of forecasting – its necessity, utility, and, at times, its undeniable limitations. Recognizing the importance of having at least some insight into the trajectory of society tomorrow, we aim to inform our decisions today.

To conclude this edition, you'll find interesting links and highlights from the past week. Please stay in the loop by subscribing directly or joining us on Substack.

Enjoy the read!

Forecasting, right and wrong

What to expect from 2024? For a large part, forecasting is economic forecasting. Apart from being very difficult, it is sometimes impossible and misses out on currently more relevant variables.1

Making economic predictions is not highly regarded in the economic profession, especially not among academics. You cannot win a Nobel Prize with making right forecasts2. It is scarcely seen as science because any thoughtful person understands that an economy is too complex to pinpoint estimates accurately. And it only becomes more complex.

But still, for every policy decision, an assessment of the consequences or a prediction is necessary. The newspaper is now filled with the question of what 2024 will bring for a reason. That's why predictions continue to play an important role, but let them be about what truly matters. And that is about more than traditional economic metrics such as economic growth or inflation. With the same frequency and urgency, we need forecasts for the effects of economic activity on nature and resilience and vice versa. This will inform policymakers about the trade-offs and lead to better decisions.

Incorrect forecasts

There are two problems with how we currently make economic forecasts: they are rarely accurate and are increasingly focused on things that are not important to policymakers.

The current track record of economists in predicting is not impressive. For example, economists did not foresee the severity of the financial crisis, overestimated the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, and did not have a prepared story for the energy crisis in advance. Of course, sudden shocks are difficult to predict. However, according to recent research, it might be better to listen to the man or woman on the street than to economists' predictions. Based on survey results, the 2008 financial crisis was on their radar earlier than (professional) forecasters.

Economists are bad at forecasting turning points, and current standard macroeconomic models can, by design, not handle changes in the economic structure (transitions). Since they are based on wisdom from the past (time series), they cannot predict dramatic shifts. And in a society that needs a great transformation, this is, let’s put it mildly, not helpful. Therefore, the current economic models are more like looking with binoculars in mirrors. So, a hall of mirrors of economic forecasting that can only predict based on past events.3 And the policy advice you get from these models is that everything should return to… equilibrium, assuming more or less that the economy should be working like in the past. Only incremental change is allowed in forecasting with macro models. Everything else is simply impossible to envision. I know making short-term forecasts is not only ‘running the model’. Also, the expert opinions of economists doing the work come in. That helps to make better forecasts (hopefully, not always). But it is impossible in the models used to forecast non-linear structural changes, not when expert judgement is added.

Furthermore, the work of forecasters is becoming increasingly challenging. Society has become more complex (see my polycrisis analysis with complexity arguments in my previous newsletter). Many factors not included in macro models increasingly impact the economy. Geopolitical uncertainties, technological disruption, extensive financial integration, and uncertainties associated with large-scale transitions - including the energy transition - make it more difficult to provide a statistical estimate of, for example, purchasing power.

These developments ensure that the outcomes of macro models say less and less about welfare developments. According to Kelly and Snower, these forces (in their work, the Globalisation, Technology, Financialisation (GTF) nexus) lead to the fact that the invisible hand conditions (those assumptions that make sure that markets deliver wellbeing) increasingly no longer hold. The conditions they distinguish are (i) perfect competition, (ii) symmetric information, (iii) diminishing returns to scale and scope, (iv) clearing markets, and (v) no externalities. These are the core assumptions, also in the micro-founded macro models. It is questionable if the forecasts make any sense if they no longer hold.

Thus, economic growth or a recession hardly affects the well-being of the average citizen in many wealthy countries.

From a recent NBER paper:

"𝙴𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚘𝚖𝚒𝚌 𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠𝚝𝚑 𝚍𝚘𝚎𝚜 𝚗𝚘𝚝 𝚊𝚙𝚙𝚎𝚊𝚛 𝚝𝚘 𝚑𝚊𝚟𝚎 𝚝𝚛𝚊𝚗𝚜𝚕𝚊𝚝𝚎𝚍 𝚒𝚗𝚝𝚘 𝚑𝚒𝚐𝚑𝚎𝚛 𝚑𝚊𝚙𝚙𝚒𝚗𝚎𝚜𝚜 𝚒𝚗 𝚛𝚒𝚌𝚑 𝚌𝚘𝚞𝚗𝚝𝚛𝚒𝚎𝚜, 𝚍𝚎𝚜𝚙𝚒𝚝𝚎 𝚛𝚒𝚜𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝙶𝙳𝙿. 𝚃𝚑𝚒𝚜 𝚒𝚜 𝚎𝚜𝚙𝚎𝚌𝚒𝚊𝚕𝚕𝚢 𝚗𝚘𝚝𝚊𝚋𝚕𝚎 𝚒𝚗 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚄𝚗𝚒𝚝𝚎𝚍 𝚂𝚝𝚊𝚝𝚎𝚜 [...]

𝙰𝚕𝚝𝚑𝚘𝚞𝚐𝚑 𝚙𝚘𝚘𝚛 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚛𝚒𝚌𝚑 𝚌𝚘𝚞𝚗𝚝𝚛𝚒𝚎𝚜’ 𝚠𝚎𝚕𝚕𝚋𝚎𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝚊𝚙𝚙𝚎𝚊𝚛𝚜 𝚝𝚘 𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚙𝚘𝚗𝚍 𝚍𝚒𝚏𝚏𝚎𝚛𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚕𝚢 𝚝𝚘 𝚎𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚘𝚖𝚒𝚌 𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠𝚝𝚑 𝚌𝚘𝚞𝚗𝚝𝚛𝚒𝚎𝚜’ 𝚠𝚎𝚕𝚕𝚋𝚎𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝚛𝚊𝚗𝚔𝚒𝚗𝚐𝚜, 𝚊𝚜 𝚒𝚗𝚍𝚒𝚌𝚊𝚝𝚎𝚍 𝚋𝚢 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚄𝚗𝚒𝚝𝚎𝚍 𝙽𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚜’ 𝙷𝚞𝚖𝚊𝚗 𝙳𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚕𝚘𝚙𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚝 𝙸𝚗𝚍𝚎𝚡, 𝚑𝚊𝚜 𝚌𝚑𝚊𝚗𝚐𝚎𝚍 𝚕𝚒𝚝𝚝𝚕𝚎 𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚛 𝚝𝚒𝚖𝚎 ... "

"𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚝𝚠𝚘 𝚖𝚊𝚓𝚘𝚛 𝚖𝚊𝚌𝚛𝚘𝚎𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚘𝚖𝚒𝚌 𝚜𝚑𝚘𝚌𝚔𝚜 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚘𝚌𝚌𝚞𝚛𝚛𝚎𝚍 𝚒𝚗 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚕𝚊𝚜𝚝 𝚝𝚠𝚘 𝚍𝚎𝚌𝚊𝚍𝚎𝚜 – 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝙶𝚛𝚎𝚊𝚝 𝚁𝚎𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜𝚒𝚘𝚗 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝙲𝚘𝚟𝚒𝚍𝟷𝟿 𝚕𝚘𝚌𝚔𝚍𝚘𝚠𝚗𝚜 - 𝚑𝚊𝚍 𝚟𝚎𝚛𝚢 𝚕𝚒𝚝𝚝𝚕𝚎 𝚒𝚖𝚙𝚊𝚌𝚝 𝚘𝚗 𝚖𝚘𝚜𝚝 𝚠𝚎𝚕𝚕𝚋𝚎𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝚖𝚎𝚊𝚜𝚞𝚛𝚎𝚜 𝚜𝚞𝚌𝚑 𝚊𝚜 𝚕𝚒𝚏𝚎 𝚜𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚜𝚏𝚊𝚌𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚑𝚊𝚙𝚙𝚒𝚗𝚎𝚜𝚜. "

"𝙾𝚟𝚎𝚛 𝚝𝚒𝚖𝚎, 𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚑 𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝙶𝙳𝙿, 𝚍𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚕𝚘𝚙𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝚌𝚘𝚞𝚗𝚝𝚛𝚒𝚎𝚜 𝚑𝚊𝚟𝚎 𝚜𝚎𝚎𝚗 𝚊 𝚍𝚛𝚊𝚖𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚌 𝚛𝚒𝚜𝚎 𝚒𝚗 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚒𝚛 𝚕𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚕𝚜 𝚘𝚏 𝚠𝚎𝚕𝚕𝚋𝚎𝚒𝚗𝚐"

And if the quality of life is no longer about employment and a percentage more or less purchasing power but about social cohesion and adaptability, then a model faces difficulties. So, economic growth may not be very interesting if the future is about whether countries such as the Netherlands will be submerged and whether there will be a livable climate.

Change the variables to forecast

Economics is about allocating scarce resources. Therefore, economically relevant forecasts for 2024 should - ideally - focus on the scarcest goods that politicians and policymakers must choose. It is about nature, social cohesion and resilience.

Forecasting nature

First, everything related to nature should be forecasted. There is now a mountain of scientific literature that, on a macro level, shows the connection between economic activity and environmental damage, such as greenhouse gas emissions, loss of biodiversity, or water pollution. I am not going to link to any research here. There is so much.

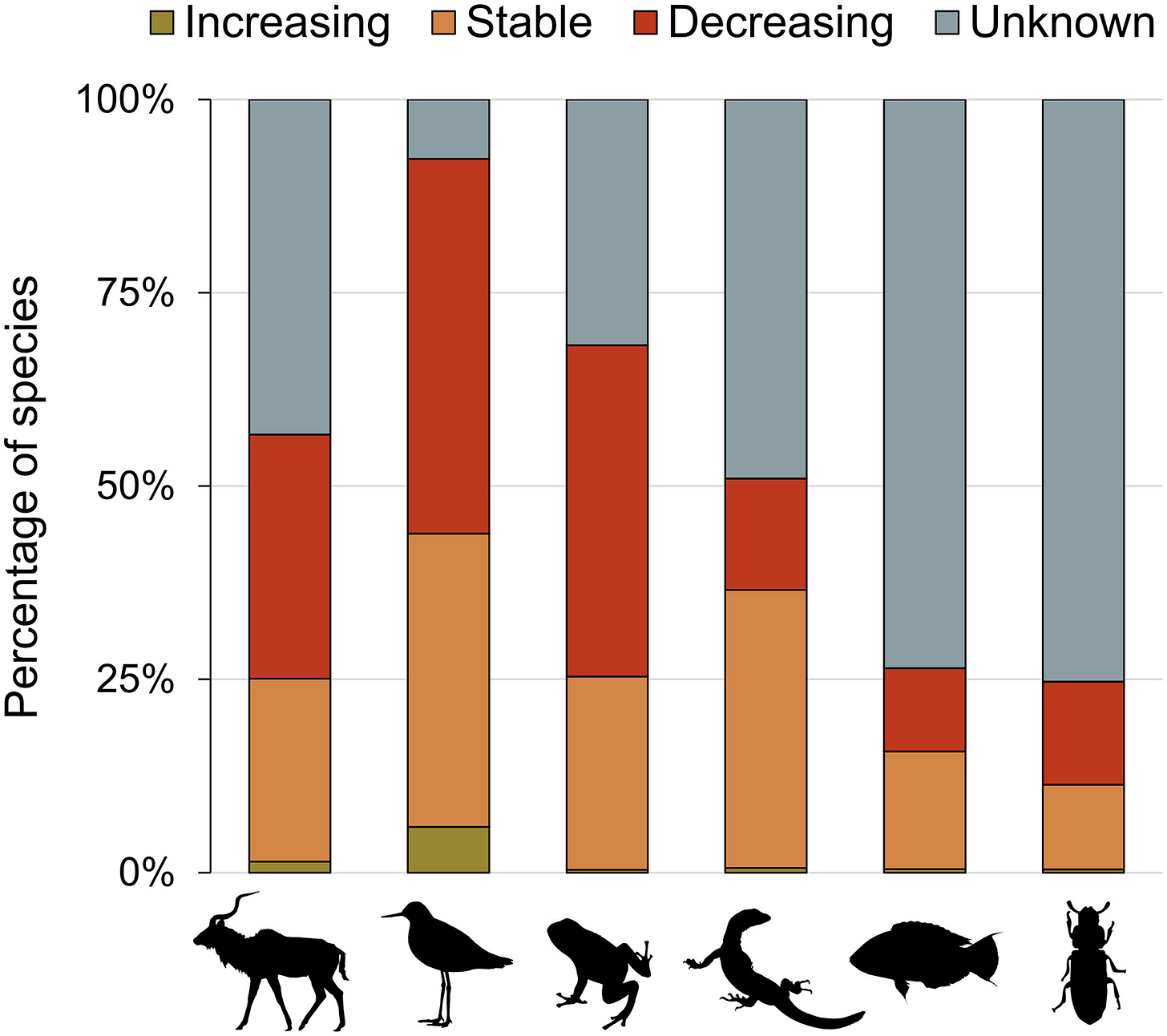

But for forecasting, the simplest indicators are roughly greenhouse gas emissions and nitrogen emissions (especially for countries like the Netherlands). But it would also help to make forecasts for species lost (would be a great, confronting headline:

“2.8% global growth forecasted in 2024 at the expense of 10004 species and with no carbon emission reduction”

So, I propose that, instead of treating ecological effects as an externality (and mumbling something that ‘someone’ should price them — even if it leads to the Sixth Mass Extinction), you could bring these effects within economic forecasting and, in that way, show the trade-offs.

It would already help if these indicators were included, for example, in the forecasts from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). What informs policymakers better than a consistent prediction of the most significant trade-offs in policy: more purchasing power, more economic, but at the expense of nature?

Forecasting resilience

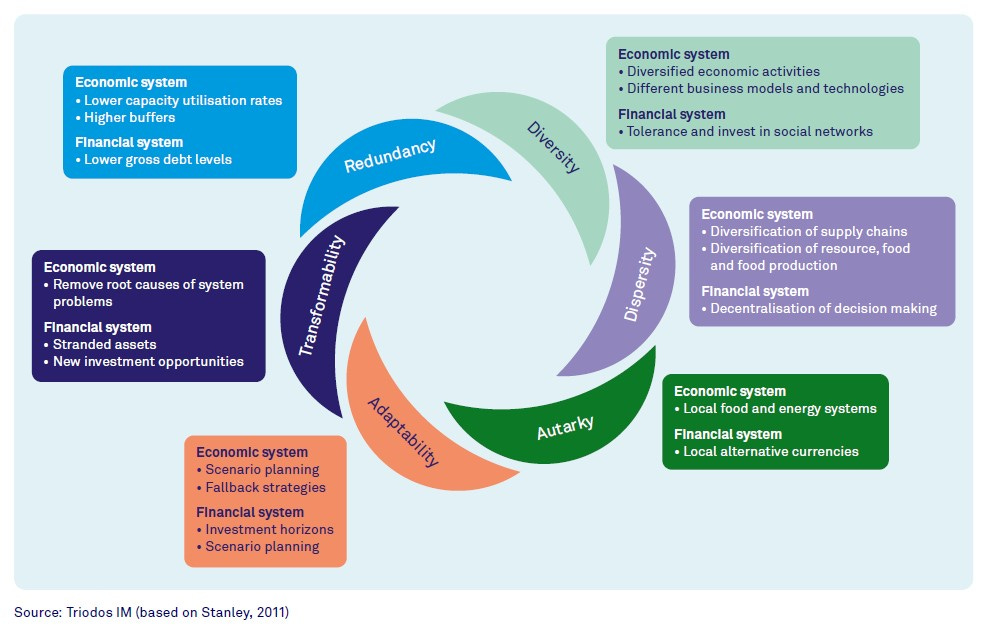

A second candidate is resilience. In last year’s economic outlook, we had a quite lengthy assessment of resilience (see here). Resilience is the capacity to buffer and adapt to change successfully, allowing core system functions or attributes to persist over time. Resilience is commonly defined in two narrower ways that arose from assumptions of their associated disciplines: engineering resilience and ecological resilience.

Engineering resilience is the time taken to return to the existing steady state following a perturbation, an idea at the heart of conventional economic theory. This idea can be seen from the way economic systems are modelled: economies are assumed to return to their ‘equilibrium’ or in some way defined stable growth state. The engineering definition, lacking a core underlying theory, does not account for critical thresholds and implicitly assumes that behaviours are stationary across time and that all other equilibria should be avoided (Allen & Holling, 2010). As a matter of fact, single-mindedly focusing on growth may cause a system to lose resilience by weakening its built-in coping mechanisms and accelerating the onset and severity of environmental shocks that will test those mechanisms.

Ecological resilience emphasises conditions far from any equilibrium steady state, where instabilities can flip the system into another regime or behaviour. Resilience is measured by the magnitude of disturbance that can be absorbed before the system changes its structure by changing the variables and processes that control behaviour. Although it was coined ecosystem resilience by Gunderson and Holling, it applies to the same extent to other systems, such as social or economic systems. That is why we rename it here as system resilience.

Economic system resilience can be defined as the capacity of an economy to endure, adapt to, and successfully recover from shocks to maintain a base level of welfare for all people at least equal to that enjoyed before the shock occurred. It encompasses preventing breakdowns from cascading into catastrophes and avoiding collapse following a catastrophe, preferably while retaining or regenerating desired system characteristics and functions.

Making an economy more resilient can take different forms and is time and state-dependent. A resilient system is founded on six key principles: Redundancy, Diversity, Dispersity, Autarky, Adaptability and Transformability.

Why is all this important? These concepts directly relate to discussions in many countries about ‘just transitions’, ‘security of existence’, and why polarisation reached new highs last year. In most economic forecasts, this discussion is limited to material prosperity. For example, there has been much policy discussion since the CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy (CPB) included poverty in the core data table of short-term forecasts. Perhaps all this attention is disproportionate because (expected) poverty is suddenly lower than in the past decades. Of course, poverty is an aspect of resilience because it relates to redundancy (buffers). But only looking at the endurance part of resilience, not the adaptability part, is a mistake.

Hence, an idea could be to enrich economic forecasts with indicators that measure broader resilience: leverage in the system (and from households) might be a suggestion, or access to and quality of basic services is another. So, forecasts about the quality and affordability of public services such as public transport, education, and healthcare. Some are already forecasted but only in terms of costs or contribution to economic growth. It would be even more useful to look at it in terms of resilience. Also, trade-offs between different areas become more visible here.

Policy considerations

I am not advocating to stop forecasting the conventional metrics generated for decades. Metrics such as economic growth, budget deficits, and inflation remain valuable for estimating tax revenues and expenditures. However, a more advantageous approach would involve comprehensively integrating diverse areas with improved predictions on the most pertinent policy considerations.

The significance of the forecasted data should not be underestimated. While information from the past, such as scores on Sustainable Development Goals, informs decisions, it is unalterable. This sets it apart from forecasts, which policymakers focus on because they hold the potential for gains. Forecasting allows policymakers to strategize and demonstrate improvements in forthcoming outcomes.

Certainly, we also require improved models, and fortunately, people are working on this. However, this is time-consuming, as developing comprehensive macroeconomic models can span several years. In the interim, there are practical steps we can take to enhance the utility of forecasts. Expanding the scope of forecasts to be more meaningful for decision-makers is one such step.

It's acceptable if these predictions are not entirely precise as long as they reasonably forecast relevant considerations. As we embark on 2024, prioritizing the accurate prediction of pertinent matters seems like a commendable resolution.

In the news

The world will look back at 2023 as the year humanity exposed its inability to tackle climate crisis, scientists say:

"𝙰𝚜 𝚜𝚌𝚒𝚎𝚗𝚌𝚎 𝚑𝚊𝚜 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚍 𝚋𝚎𝚢𝚘𝚗𝚍 𝚊𝚗𝚢 𝚍𝚘𝚞𝚋𝚝, 𝚐𝚕𝚘𝚋𝚊𝚕 𝚝𝚎𝚖𝚙𝚎𝚛𝚊𝚝𝚞𝚛𝚎𝚜 𝚠𝚘𝚞𝚕𝚍 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚞𝚎 𝚝𝚘 𝚛𝚒𝚜𝚎 𝚊𝚜 𝚕𝚘𝚗𝚐 𝚊𝚜 𝚑𝚞𝚖𝚊𝚗𝚒𝚝𝚢 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚞𝚎𝚜 𝚝𝚘 𝚋𝚞𝚛𝚗 𝚏𝚘𝚜𝚜𝚒𝚕 𝚏𝚞𝚎𝚕𝚜 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚏𝚘𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚝𝚜. 𝙸𝚗 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚢𝚎𝚊𝚛𝚜 𝚊𝚑𝚎𝚊𝚍, 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚑𝚎𝚊𝚝 “𝚊𝚗𝚘𝚖𝚊𝚕𝚢” 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚝𝚊𝚜𝚝𝚛𝚘𝚙𝚑𝚎𝚜 𝚘𝚏 𝟸𝟶𝟸𝟹 𝚠𝚘𝚞𝚕𝚍 𝚏𝚒𝚛𝚜𝚝 𝚋𝚎𝚌𝚘𝚖𝚎 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚗𝚎𝚠 𝚗𝚘𝚛𝚖, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗 𝚋𝚎 𝚕𝚘𝚘𝚔𝚎𝚍 𝚋𝚊𝚌𝚔 𝚘𝚗 𝚊𝚜 𝚘𝚗𝚎 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚌𝚘𝚘𝚕𝚎𝚛, 𝚖𝚘𝚛𝚎 𝚜𝚝𝚊𝚋𝚕𝚎 𝚢𝚎𝚊𝚛𝚜 𝚒𝚗 𝚙𝚎𝚘𝚙𝚕𝚎’𝚜 𝚕𝚒𝚟𝚎𝚜"

Research About transition pains: I again realised it is not inability — we can make the world more sustainable if we wish to — it is power and loss aversion that leads to resistance

“....𝚍𝚛𝚊𝚠𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝚝𝚑𝚒𝚜 𝚖𝚘𝚛𝚎 𝚗𝚞𝚊𝚗𝚌𝚎𝚍 𝚙𝚒𝚌𝚝𝚞𝚛𝚎, 𝚊 𝚝𝚛𝚊𝚗𝚜𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 𝚙𝚊𝚒𝚗 𝚕𝚎𝚗𝚜 𝚜𝚑𝚒𝚏𝚝𝚜 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚏𝚘𝚌𝚞𝚜 𝚝𝚘𝚠𝚊𝚛𝚍𝚜 𝚋𝚎𝚑𝚊𝚟𝚒𝚘𝚞𝚛 𝚋𝚎𝚢𝚘𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚗𝚗𝚘𝚟𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚜𝚞𝚖𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚘𝚛 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚍𝚞𝚌𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚝𝚘𝚠𝚊𝚛𝚍 𝚟𝚊𝚛𝚒𝚎𝚝𝚒𝚎𝚜 𝚘𝚏 (𝚍𝚒𝚜)𝚎𝚗𝚐𝚊𝚐𝚎𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚝 𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚑 𝚝𝚛𝚊𝚗𝚜𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚜, 𝚜𝚞𝚌𝚑 𝚊𝚜 𝚙𝚘𝚕𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚌𝚊𝚕 𝚙𝚘𝚜𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚜𝚘𝚌𝚒𝚊𝚕 𝚖𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚜, 𝚘𝚛 𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚒𝚜𝚝𝚊𝚗𝚌𝚎. 𝚆𝚑𝚒𝚕𝚎 𝚖𝚘𝚋𝚒𝚕𝚒𝚣𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚒𝚜𝚝𝚊𝚗𝚌𝚎 𝚝𝚘 𝚌𝚑𝚊𝚗𝚐𝚎 𝚊𝚛𝚎 𝚘𝚗𝚕𝚢 𝚝𝚠𝚘 𝚙𝚘𝚜𝚜𝚒𝚋𝚕𝚎 𝚌𝚘𝚙𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚙𝚘𝚗𝚜𝚎𝚜 𝚘𝚏 𝚖𝚊𝚗𝚢, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚠𝚑𝚒𝚕𝚎 𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚒𝚜𝚝𝚊𝚗𝚌𝚎 𝚌𝚊𝚗 𝚊𝚕𝚜𝚘 𝚋𝚎 𝚝𝚛𝚒𝚐𝚐𝚎𝚛𝚎𝚍 𝚋𝚢 𝚎𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚘𝚖𝚒𝚌 𝚘𝚛 𝚙𝚘𝚕𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚌𝚊𝚕 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚜𝚒𝚍𝚎𝚛𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚜 𝚋𝚎𝚢𝚘𝚗𝚍 𝚎𝚖𝚘𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚜, 𝚎𝚖𝚘𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚜 𝚌𝚊𝚗 𝚋𝚎 𝚙𝚊𝚛𝚝 𝚘𝚏 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚙𝚞𝚣𝚣𝚕𝚎 𝚘𝚏 𝚋𝚎𝚝𝚝𝚎𝚛 𝚎𝚡𝚙𝚕𝚊𝚒𝚗𝚒𝚗𝚐 𝚗𝚘𝚝 𝚘𝚗𝚕𝚢 𝚜𝚘𝚌𝚒𝚊𝚕 𝚖𝚘𝚟𝚎𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚜, 𝚋𝚞𝚝 𝚊𝚕𝚜𝚘 𝚜𝚘𝚌𝚒𝚊𝚕 𝚒𝚗𝚎𝚛𝚝𝚒𝚊, 𝚜𝚘𝚌𝚒𝚊𝚕 𝚏𝚛𝚊𝚐𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚊𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗, 𝚙𝚘𝚕𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚌𝚊𝚕 𝚙𝚘𝚜𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚒𝚗𝚐, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚒𝚜𝚝𝚊𝚗𝚌𝚎 𝚝𝚘 𝚜𝚞𝚜𝚝𝚊𝚒𝚗𝚊𝚋𝚒𝚕𝚒𝚝𝚢 𝚝𝚛𝚊𝚗𝚜𝚒𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗𝚜"

IMF blog about Slowbalisation: I'm curious to see how that will develop in 2024. With numerous elections, geopolitical tensions, and many factors at play, many anticipate another year of slowbalisation.

FT outlook on ‘cleaner capitalism’: Or at least the trends that will influence sustainable finance (for cleaner capitalism you need much more): my thoughts and additions here

On the German energy transition: Carbon emissions in Germany hit a 𝟳𝟬-𝘆𝗲𝗮𝗿 𝗹𝗼𝘄, a remarkable achievement with a 46% decrease from the reference year 1990, equivalent to a 1.4% annual reduction. While this success is impressive, there's a challenge ahead. To meet the 2030 goal, carbon emissions need to drop an additional 35% in 2030 (from 672 Mt to 440 Mt), implying an annual decrease of 5%!

That’s all for this week. I promise to keep it shorter next time. 😀

Take care.

Hans

This is a longer version of article published in Het Financieele Dagblad (in Dutch): Laat economen hun voorspellingen richten op zaken die echt van belang zijn

Although you could say that you can win a Nobel Prize with wrong forecasts. For example, the 2018 Nobel Laureate William Nordhaus was awarded the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel because of (among other things) his DICE model. That model produced wrong forecasts about the relationship between economic activity and climate change. See Steve Keen’s debunk: The appallingly bad neoclassical economics of climate change. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344034609_The_appallingly_bad_neoclassical_economics_of_climate_change#fullTextFileContent [accessed Jan 05 2024].

In 2009, I attempted to simulate the unfolding financial crisis using a macro-econometric model (NiGEM). However, the endeavour proved to be insurmountable. The model, quite logically, is based on historical data, rendering it incapable of offering insights into the present, let alone predicting the future.

Based on WWF site: experts calculate that between 0.01 and 0.1% of all species will become extinct each year. If the low estimate of the number of species out there is true - i.e., there are around 2 million species on our planet - then that means between 200 and 2,000 extinctions occur yearly. This correlates according to the IPBES 2022 report that economic growth has adverse effects on biodiversity.

Great read, Hans. You might like our piece about resilience: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4667697.