#1 Tipping points economics

Looking back on 2023: The first polycrisis year

Hi all,

As the year draws closer, I've decided: I'm relaunching a newsletter. Much like what many of you have come to expect from me, this newsletter will delve into topics spanning economics, (sustainable) finance, sustainability, activism, and the interconnected facets of these realms. My ongoing quest to comprehend the intricacies of the economic system and drive toward systemic change is reflected in the new name of this newsletter, "Tipping Points Economics." You can either subscribe directly or join on Substack to stay updated.

In this iteration, I'm concluding with an in-depth root cause analysis of the Polycrisis (mind you, the term "polycrisis" only captures the symptoms). Towards the end, I'll wrap up with curated links and noteworthy news. Dive in and enjoy the journey!

2023 polycrisis

2023 was a polycrisis year. Time to (also) delve into the root causes. Because only there can we find solutions. The rest is real-world problems that distract us from those underlying problems.

A polycrisis refers to an extraordinary scenario wherein multiple crises concurrently afflict society. The interconnectedness of various global systems exacerbates the negative impacts, surpassing the cumulative harm that would have arisen if the host systems were not profoundly entangled. Consequently, the confluence of these interacting crises significantly and irreversibly undermines humanity's prospects for the future. Adam Tooze claimed almost a year ago that diagnosing the world as being in polycrisis was the right assessment.

Looking back to 2023, it is hard to be positive, get positive or be optimistic. We can safely state that the diagnosis of Tooze from last year still holds. It was not a good year for those who had hoped for a bright future or that 2023 would be the year of a tipping point towards a more sustainable world. It has been the year of extreme weather events, temperature records, rainfall records, ice melting records, wars without foreseeable ends, polarization, meagre results in the climate summits, et cetera. I need to replicate all the details of the challenges of 2023 wrong; for an overview, see this article which includes the figure below.

And there was positive news for those who thought of stopping reading because they thought I was too pessimistic. Massive increase in renewable energy, for example. Or new technologies that help a more sustainable world to come closer. Some say it might even be seen as the year of ‘the beginning of the end"‘ for the fossil fuel area. And alas, also in the category positive: a big year for climate litigation.

Is AI adding to the Polycrisis or is it a relief?

And there is another element that some might judge as positive, but I think is more troublesome: artificial intelligence. 2023 has been the year of AI. I don’t want to go in-depth here about AI (there is so much to say…), but some tentative remarks. With every technology, there is a tendency to write exciting stuff about doom scenarios (it will take our jobs!) or utopian scenarios (it solves everything!). We saw it with IT, and I remember pretty vividly the turning of the century and the internet boom, where the idea was that everything might be different. And so, the same happens nowadays with AI.

The International Monetary Fund did some excellent work to balance the views. They take three important topics: productivity developments, inequality and concentration, and make for every topic two scenarios (forks).

Productivity Growth Fork: A scenario where AI has limited impact, potentially due to slow adoption and challenges in organizational changes, and a scenario where widespread AI application leads to significant productivity boosts, transforming the economy (the latter is the favourite of many economists that have to explain the equity valuations of big tech companies, others are more cautious).

Income Inequality Fork: AI could replace high-paying jobs in a higher-inequality future, leading to a polarized labor market. Conversely, AI could assist less skilled workers in a lower-inequality future, potentially reducing income disparities.

Industrial Concentration Fork: In a higher-concentration future, large firms with extensive resources dominate by leveraging expensive proprietary AI. An open-source AI ecosystem benefits smaller businesses in a lower-concentration future, fostering competition and innovation.

Essentially, we don’t know. We only know that there is much to worry about, which is more far-reaching than the macro-economic consequences, such as ethical, privacy, human rights and human dignity questions.

The root causes of the polycrisis

I only want to dive into the root causes and its complexities: the first year of the polycrisis or the next level of polycrisis. There are a few root causes: wickedness (complexity and uncertainty), scale (unprecedented…) and, in the end, worldviews and governance.

Wickendness

Wicked problems can be described as problems with common characteristics:

① They can’t be formulated definitively.

② They don’t have a “stopping rule” or an inherent logic that signals when they are solved.

③ Their solutions are not true or false, only good or bad.

④ There is no way to test their solutions.

⑤ They cannot be studied through trial and error. Their solutions are irreversible. ⑥ There is no end to the number of solutions or approaches to a wicked problem.

⑦ Each wicked problem is unique.

⑧ Wicked problems can always be described as symptoms of other problems.

⑨ The way a wicked problem is described determines its possible solutions.

⑩ Planners who work on wicked problems “are liable for the consequences of the solutions they generate; the effects can matter greatly to the people touched by those actions.”

Scale

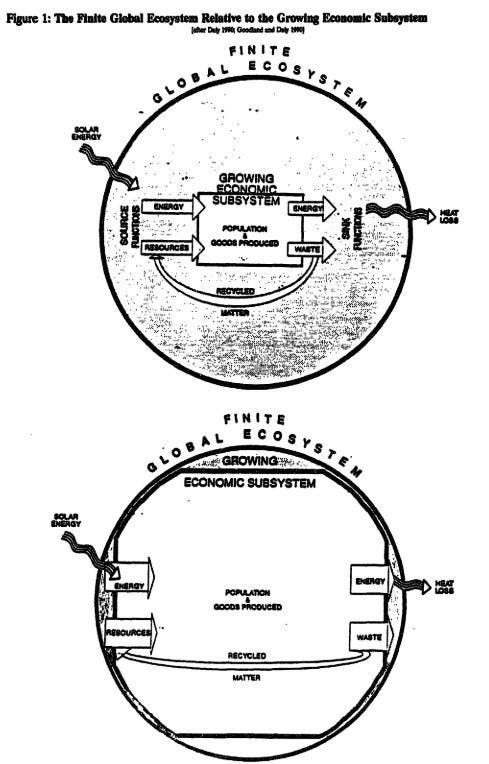

We may have had some of these interconnected, wicked problems, but the scale of it is entirely new. And scale is a variable that needs to be included in (economic) analysis. It makes things different, a classic analysis in this respect is from Herman Daly; The empty world versus the full world vision.

source: Goodland, Daly, Serafy, 1991

To quote Herman Daly:

“Since the mid-twentieth century, the world population has more than tripled—from two billion to over seven billion. The populations of cattle, chickens, pigs, and soybean plants and corn stalks have as well. The non-living populations of cars, buildings, refrigerators, and cell phones have grown even more rapidly. All these populations, both living and non-living, are what physicists call “dissipative structures”—that is, their maintenance and reproduction require a metabolic flow, a throughput that begins with depletion of low-entropy resources from the ecosphere and ends with the return of polluting, high-entropy waste back to the ecosphere. This disrupts the ecosphere at both ends, an unavoidable cost necessary for the production, maintenance, and reproduction of the stock of both people and wealth. Until recently, standard economic theory ignored the concept of metabolic throughput, and, even now, its importance is greatly downplayed.” (see here)

Simplified: In a world with abundant resources, a fisherman with a more efficient boat catches more fish (empty world). However, in a world nearing its limits (full world), the fisherman must invest in a larger boat to catch any fish before it's too late. The conventional idea that capital and technology can seamlessly replace nature is challenged when we exceed planetary boundaries. This undermines a fundamental economic assumption of substitutability between different forms of capital (from nature to financial) and jeopardizes the very foundation of our lives. This challenges the notion of perpetual growth as we face the visible constraints of our environment.

Worldviews and governance

Recognizing the issue's complexity and the scale of the challenges is just the beginning of understanding the root causes and is definitely not an answer. As also explained here, The ‘limits to growth’ as much as many other publications of that time (like the population bomb from Ehrlich) read like an answer. They were thus eagerly instrumentalised and kept in the domain of discourse instead of helping for a deeper solution (although Meadows did quite some work on that).

We must turn our gaze inward to unravel the origins of these problems. Examining the various forms of capitalism across diverse nations, including China, India, and Russia, reveals a common thread: a lack of regard for ecological boundaries and a noticeable absence of a collective ethos.

In these capitalist systems, where markets dominate, and labour is commodified, a critical error lies in the unwavering belief that the sum of individual preferences automatically translates to social welfare. This foundational misconception overlooks the fact that, for the greater good, there are occasions when individuals must be constrained. It necessitates a shift beyond mere financial contributions such as taxes, extending into the realm of personal sacrifices—allocating time for others and occasionally refraining from actions that may personally benefit but harm the collective well-being. The key lies in recognizing that societal progress sometimes demands actions against individual preferences.

This is about the dominant worldview embedded in capitalism: individualism. With such a worldview, it is hard to combat system problems.

Therefore, we come to governance. This governance is set up in such a way (with apparent differences between countries) to foster markets and, in a reductionist way, increase profit and growth as yardsticks for well-being. This governance disregards scale and wickedness, so continuing like this aggravates the problem.

Additionally, these governance structures are primarily organised on a nation-state level. We have larger problems than can be solved with nation-states (and a few problems between nation-states). International governance still fails or goes too slow, as the COPs show.

Root causes that are difficult to overcome are worldviews and governance. If we do not address that and only look at the consequences (polycrisis), we cannot solve anything.

Polysolutions

What to do? The response to these monumental challenges is often rooted in solutionism, the belief that benign solutions, often involving technology, exist for all environmental and social problems. However, this notion needs to be more accurate. There are no quick fixes, and clinging to technological optimism can hinder profound transformations, maintaining the status quo.

Engaging in discussions seeking radical change, including worldviews and governance, is a part of what should happen. If we can envision degrowth or post-growth as an optimistic outcome, we have won a battle of worldviews. A growth-addicted world economy has a long way to go to get there.

To make it smaller, some ideas:

✅ Find novel ways to connect with communities and each other without depleting natural resources.

✅ Work on resilience, both in resisting shocks and enhancing the ability of individuals and societies to adapt.

✅ Reimagine life by learning from other cultures and our past.

✅ Demonstrate bottom-up what is possible, showcasing how we can lead fulfilling lives with a lower ecological footprint.

We probably need much more. We need to look for those ideas that are the most efficient way to shift modes and lead to change: tipping points.

In the news

Paper about divesting. Conclusion: So, despite the massive pledges and net-zero ambitions in the financial sector, the impact of divesting in the market remains limited. What to do? see here: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/hans-stegeman_divesting-carbonpricing-ffnpt-activity-7146069411139907584-urG8?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop

Wise words by Robert Costanza in 👉Nature last week: "𝚃𝚑𝚎 𝚙𝚞𝚛𝚜𝚞𝚒𝚝 𝚘𝚏 𝙶𝙳𝙿 𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠𝚝𝚑 𝚊𝚝 𝚊𝚕𝚕 𝚌𝚘𝚜𝚝𝚜 𝚒𝚜 𝚊𝚗 𝚘𝚞𝚝𝚍𝚊𝚝𝚎𝚍 𝚙𝚊𝚛𝚊𝚍𝚒𝚐𝚖 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚌𝚕𝚊𝚒𝚖𝚜 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚊𝚕𝚕 𝚙𝚎𝚘𝚙𝚕𝚎 𝚠𝚊𝚗𝚝 𝚒𝚜 𝚖𝚘𝚛𝚎 𝚒𝚗𝚌𝚘𝚖𝚎 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚜𝚞𝚖𝚙𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚑 𝚗𝚘 𝚕𝚒𝚖𝚒𝚝𝚜. 𝙸𝚝 𝚊𝚜𝚜𝚞𝚖𝚎𝚜 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚖𝚊𝚛𝚔𝚎𝚝 𝚎𝚌𝚘𝚗𝚘𝚖𝚢 𝚌𝚊𝚗 𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠 𝚏𝚘𝚛𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚛, 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚖𝚊𝚜𝚜𝚒𝚟𝚎 𝚒𝚗𝚎𝚚𝚞𝚊𝚕𝚒𝚝𝚢 𝚒𝚜 𝚓𝚞𝚜𝚝𝚒𝚏𝚒𝚎𝚍 𝚝𝚘 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚟𝚒𝚍𝚎 𝚒𝚗𝚌𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚒𝚟𝚎𝚜 𝚝𝚘 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚖𝚘𝚝𝚎 𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠𝚝𝚑, 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚎𝚏𝚏𝚘𝚛𝚝𝚜 𝚝𝚘 𝚊𝚍𝚍𝚛𝚎𝚜𝚜 𝚌𝚕𝚒𝚖𝚊𝚝𝚎 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚘𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚛 𝚎𝚗𝚟𝚒𝚛𝚘𝚗𝚖𝚎𝚗𝚝𝚊𝚕 𝚊𝚗𝚍 𝚜𝚘𝚌𝚒𝚊𝚕 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚋𝚕𝚎𝚖𝚜 𝚖𝚞𝚜𝚝 𝚗𝚘𝚝 𝚒𝚗𝚝𝚎𝚛𝚏𝚎𝚛𝚎 𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚑 𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠𝚝𝚑. 𝙸𝚝 𝚜𝚞𝚙𝚙𝚘𝚜𝚎𝚜 𝚝𝚑𝚊𝚝 𝚐𝚛𝚘𝚠𝚝𝚑 𝚒𝚜 𝚝𝚑𝚎 𝚜𝚘𝚕𝚞𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 𝚝𝚘 𝚊𝚕𝚕 𝚒𝚕𝚕𝚜. 𝙸𝚝 𝚒𝚜𝚗’𝚝."

Climatelitigation had a blockbuster year in 2023: Courts worldwide carefully weighed evidence and arguments in pivotal trials and hearings. Landmark rulings marked big wins in holding governments accountable for climate inaction or denial, while the number of new climate cases kept on ticking. With the count of climate lawsuits pushing 2,500 globally, it's crystal clear that courts have become a vital battleground for championing climate justice and ensuring accountability isn't just a buzzword.

We need to stop advertising! In practice, advertisement leads to overconsumption. The US advertisement agency is proud that every dollar of add spending supported nearly $21 of sales. Overconsumption (so buying things you don't need that don't make you happy beyond the dopamine shot you get) is one of the forces that (unnecessarily!) destroy our ecosystems. So, advertisement is one of the 𝐰𝐞𝐚𝐩𝐨𝐧𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐚𝐬𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐮𝐦𝐩𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 that potentially lead to mass destruction...My solution here

That’s all for this year. Have a nice year-end!

Take care.

Hans

What are wonderful newsletter Hans, very resourceful!