Hi all,

We live in brutal times. Times where we have reached (already!) 1.5 degrees of global warming last year. Times where the wealthiest 1% on earth have already used up the carbon budget for this year.

Also, a time when it is so easy to be pessimistic about almost anything if you are looking for positive change.

But this is luckily not the whole story. Even not when we see populist votes winning, Trump inaugurated next week, and plutocrats like Elon Musk radicalising, even not when big tech (Zuck goes full Musk) aligns with the new Trump reality. And also not when US finance leaves the biggest climate finance alliance GFANZ).

No. Although it seems all negative, many people—less outspoken, noisy, and influential—want the world to become a better place. They want an energy transition. They believe we could or should buy less, eat more healthily, and care more about each other. You could call it the undercurrent; you could also call it a silent majority.

We discovered this hopeful message when we published our ‘different-style’ economic outlook for the Netherlands over a week ago.

We (my colleague Ernst Hobma and I) started by assessing the main bottlenecks in the Dutch economy and translating them into ‘transition language’: what are the five most significant changes that need to happen to make the Dutch economy future-proof? Of course, these transitions are not unique to the Dutch economy; they can easily be applied to any economy.

Based on that assessment, we constructed a survey and hired an agency (Motivaction) to optimise it. We also held the study under a representative Dutch panel.

The main conclusions:

Support for Change vs. Resistance

In every transition, a significantly larger group of Dutch citizens favoured change than those opposed it. On average, 50% support change, while only 15% oppose it.Behavioural Adoption and Transition Readiness

The largest group already adopting expected behaviours—or planning to do so—is seen in the energy transition (e.g., reducing air travel) and the social transition (e.g., engaging in volunteer work), with 22% of people in each case.

The well-being transition and food transition lag behind, with adoption rates below 15%, far from the 25% tipping point where systemic change accelerates. However, including those who social norms or price incentives might influence could help bring these transitions closer to the tipping point.

The resource transition (e.g., reducing raw material use) remains the furthest from a tipping point, with only pioneers taking action. Few people plan to join, and price mechanisms have minimal impact.

Demographic Variations

Resistance to change is lowest among seniors (65+) and young people (under 25).

Older adults (55+) tend to take more action themselves, while younger people are slightly less likely—or less able—to act.

Higher-educated individuals are more open to transitions than those with lower education levels.

Expectations for Action

Over 70% of Dutch citizens expect businesses to act more quickly to reduce CO₂ emissions and resource consumption in energy, food, and resources.

Most expect the government to improve social cohesion by keeping community centres and sports facilities open and subsidizing initiatives that strengthen local communities.

However, people also think that they are responsible for getting change. We don’t have to wait for politicians.

Meat Consumption Policies

Government policies to discourage meat consumption have little support. Most non-vegetarians (68%) express no interest in reducing meat consumption.

We conclude that people are not stupid. They understand that we need more radical action, but most don’t know how and fear that change will worsen them.

Our call to action is simple for all Dutch citizens who consider sustainability transitions necessary: share this message with others. Please share it with your friends, neighbours, local government, sports club, bank, pet, the companies you buy from, and even strangers on the street. This is how social norms shift, bringing the tipping point ever closer.

It might not surprise me if similar research in other countries yields the same results: People are willing—at least a significant, silent majority are. Question number one is how to mobilise them.

And remember: don’t let yourself be overwhelmed by all the negative news. There is always a spark of hope—friends, like-minded individuals, neighbours, and family striving to improve the world for themselves and future generations and others around the globe. Courageous people who take action, try new things and create change—not just by writing and analyzing, as I often do, but by rolling up their sleeves and making it happen.

The whole report can be found here (unfortunately, in Dutch). Below is a slightly shortened and slightly adapted translated version.

The Dutch Economy in 2025: A Major Overhaul Can Begin

The Dutch Economy: A Balancing Act

At first glance, the Dutch economy seems to be doing quite well. Unemployment is low, government debt is under control, and while inflation remains high, it is on a downward trend. The Netherlands continues to earn more from international trade than it spends abroad. Pension funds are well-funded; on average, Dutch citizens are happier and wealthier than residents of many other countries.

Yet, the foundation is cracking. The housing market is overheating, and the labour market is under significant strain. Solutions to major bottlenecks—such as the shortage of construction space, high nitrogen emissions, and the decline in public services—are not yet in sight. The climate crisis is also knocking on the Netherlands' door, while geopolitical uncertainty impacts the Dutch economy and its citizens.

Gradually, there is growing awareness that part of the Dutch economic model—based on relatively cheap energy and well-educated but comparatively inexpensive labour—is no longer sustainable. The labour supply is shrinking due to ageing and reduced migration. With the closure of Groningen’s gas fields, the Netherlands has transitioned into an energy importer. Meanwhile, fossil fuels are still being burned, and resource consumption exceeds what the planet can sustain.

This underscores the urgent need for a major overhaul. The aim is to transition to an economy less reliant on fossil fuels and foreign resources, where sustainably produced food is the norm, and well-being and social relationships take centre stage. Instead of focusing on marginal changes in economic growth, unemployment, or government debt, Triodos Bank's outlook emphasises the paradigm shift the Dutch economy requires.

Using data from a representative sample of the Dutch population, we explore how people view these significant changes. Are they taking action themselves? What role do they see for the government and businesses, and what would motivate them to act even faster?

Based on this survey, we believe many of these changes—also known as transitions—are nearing a tipping point. Despite stark political divides, many Dutch people are ready for change. A majority is not always necessary; a substantial minority can be enough to drive systemic change, especially when resistance to change is low. Our findings provide optimism, showing that the polarisation in political debates does not necessarily obstruct these transitions.

The year 2025 could mark the beginning of this much-needed transformation. The urgency is already felt among the Dutch population.

The Five Major Transitions

For years, numerous reports have emphasized the necessity of structural changes to the Dutch economy. In some areas, the Netherlands has already formulated objectives for these transitions.

Energy Transition

The energy transition target is clear: a 55% reduction in emissions by 2030. This goal is legally binding, yet the Environmental Assessment Agency (PBL) warns that current policies are insufficient to meet it. Achieving this target requires extraordinary efforts from the government, central greenhouse gas-emitting companies, and households.Resource Use

The national goal for resource use is equally ambitious: by 2050, the Netherlands aims to be fully circular. Achieving this transformation involves significant work. The PBL suggests every possible strategy to reduce resource consumption: producing products more sustainably, ensuring longer lifespans, making them repairable and dismantleable, and shifting from ownership to sharing models. Moreover, individuals will need to adopt more sustainable consumption habits.Agriculture and Food Systems

The agricultural sector faces well-documented challenges. Nitrogen emissions are too high, and manure issues continue to accumulate. These issues demand bold policy choices, including reducing intensive livestock farming and transitioning to plant-based and organic diets. However, this shift toward a sustainable agricultural and food system is progressing too slowly.These three transitions primarily concern the future—what sustainability experts call “well-being later.” The Netherlands is not performing well on this front. However, challenges also remain in the present.

Health and Well-being

The Dutch population doesn’t always eat or live healthily. Without policy changes, obesity, driven by unhealthy lifestyles and dietary habits, is expected to increase further in the coming years. While many Dutch citizens report being generally satisfied, stress among young people is a growing concern. Well-being also encompasses financial security and affordable housing. Despite low unemployment rates, people worry about their incomes and housing availability.Social Cohesion and Politics

Concerns about how society interacts and The Hague's political climate are mounting. Different groups within society are increasingly disconnected, threatening social cohesion: when people don’t know each other, they can’t understand one another’s expectations or work together to solve problems.

These transitions are essential, but they raise critical questions. Do we, as Dutch citizens, want them? Where do they currently stand? Are some more advanced than others? How can they be accelerated?

A conventional economic outlook does not offer answers to these questions. Such analyses typically focus on a stagnating economy, a tight labour market, and strategies to boost economic growth slightly. Structural changes are often absent from forecasts, which tend to prioritize short-term economic cycles.

But given the urgent challenges facing the Netherlands—and the world—a standard outlook is no longer sufficient. Further growth of the current unsustainable economic system, rooted in economic growth and profit maximization regardless of societal or environmental costs, is untenable and economically unwise.

So, we have been looking for social tipping points (see also my previous substack on tipping point investing). Tipping points are moments when relatively small changes lead to a significant shift in the system. Social tipping points occur, for example, when the behavioural change of a small group leads to a shift in societal norms, causing many more people to change their behaviour in a relatively short time. Social tipping points are not a new phenomenon. The saying “Once one sheep crosses the bridge, the rest will follow” refers to social tipping points. Reaching social tipping points around sustainable behaviour could significantly contribute to advancing sustainability.

To ensure long-term well-being, we must embrace transitions—significant societal changes driven by technological or social developments. Transitions are rarely straightforward. Established interests—such as companies profiting from the current system—often resist change. Likewise, individuals who feel uncertain about alter or fail to see its necessity may fear things will worsen. Resistance tends to intensify as a tipping point approaches.

However, many people are already working toward these necessary transitions. Change is underway from neighbourhood initiatives to energy cooperatives, from sustainable farming collectives to repair cafés. Not everyone needs to be a frontrunner: research suggests that engaging 25% of the population is enough to establish a new normal and push society past a tipping point.

The Five-Transitions Survey

We conducted a representative survey of 1,048 Dutch citizens in collaboration with the research agency Motivaction. This survey asked respondents about their views on five transitions essential for creating a sustainable, well-being-focused society. These questions aimed to identify social tipping points—moments when a transition becomes irreversibly accelerated and leads to a new societal norm.

In the survey, participants were asked whether they believe a (faster) transition is necessary in each of the five areas. They were also asked who drives such transitions: citizens, businesses, or the government. Additionally, respondents shared specific actions they are already taking in these transitions and the factors that might motivate them to change their behaviour. For instance:

We also included questions about the extent to which people believe their behaviour influences the behaviour of others and vice versa.

In addition to averages, the data allows us to compare different groups, such as young vs. old, men vs. women, various educational levels, and differing social identities. This comparison offers a nuanced view of where consensus exists and where opinions diverge across societal groups.

What the Dutch Think

Conclusion 1: Far More Dutch People Support Change Than Oppose It

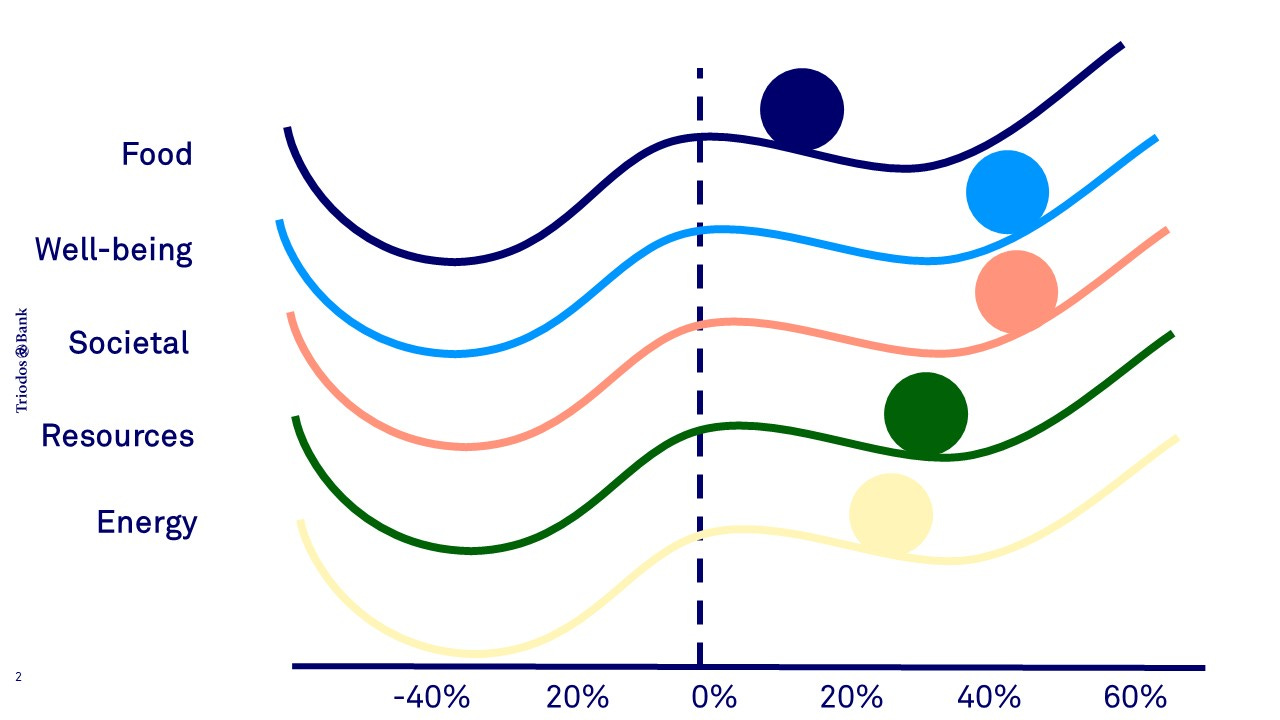

A large majority of Dutch citizens believe the five transitions are necessary. Figure 2 illustrates the level of support for each of the five transitions among the Dutch population. The horizontal axis shows the percentage of people who support a transition minus the percentage explicitly opposed to it.

Most respondents believe that a healthy lifestyle—eating according to the Dutch Nutrition Centre guidelines and exercising regularly—should become the norm in the Netherlands. A majority also feel that people should be more involved in their local communities, such as volunteering or joining local organizations. Nearly half of respondents support faster reductions in CO₂ emissions and limiting resource use in the Netherlands. Four in 10 respondents support transitioning to a local, organic, and plant-based diet.

Only a small portion of respondents is explicitly against the five transitions. This group varies in size: 10% oppose well-being and social transitions, and 25% are against the food transition, with resistance primarily focused on giving up meat and dairy. However, there is little opposition to eating locally and organically.

Across all transitions, the group supporting change is larger than the group opposing it. People place the most significant importance on promoting social cohesion and encouraging a healthy lifestyle.

Notably, older adults and people with lower levels of education value social cohesion the most, more than other groups. Younger people prioritize reducing CO₂ emissions far more than any other transition.

Conclusion 2: Responsibility Varies by Transition

Most respondents believe that something must be done for each of the transitions. The percentage of people who expect no action from businesses, citizens, or the government is low, ranging between 15% and 30% across all transitions.

However, opinions on who should act first are much more divided. Many respondents believe multiple actors need to take action simultaneously. Figure 3 illustrates the expectations for each transition, showing who respondents think should take the lead. The chart includes government responsibilities like regulation and pricing, with respondents allowed to select multiple answers.

Businesses are seen as key actors in ecological transitions involving food, energy, and resources. More than 70% of respondents expect companies to reduce CO₂ emissions and resource consumption more quickly than they currently do. Respondents also expect citizens to take action themselves. Government action, such as regulatory measures, receives less support for these transitions. However, a significant minority would still like more decisive government leadership.

This perspective is markedly different in the case of social cohesion. Here, respondents see much more room for government involvement alongside personal initiative. Suggestions include keeping community centres and sports fields open and subsidizing projects that unite people. Strengthening social cohesion is a broadly supported goal, with backing across all education levels and age groups.

Respondents express a diverse set of expectations on the topic of food transitions. Many expect action from themselves, but they also want businesses to contribute. However, government policies to discourage meat and dairy consumption are met with little enthusiasm. For example, most non-vegetarians are not interested in giving up meat. Policies like a meat tax may hinder progress despite being justified under the principle of “polluters pay.” Conversely, taxing imported or pesticide-treated products enjoys majority support. Many respondents are open to buying local or organic products only if they become the cheapest option. Overall, there is a positive attitude toward local and organic food, but price remains a significant driver of behaviour.

Respondents primarily view health as their responsibility, though many also expect contributions from the government. Examples include taxing unhealthy food or banning the sale of candy, snacks, and chips in schools and hospitals. A substantial minority also expects efforts from businesses to promote healthier lifestyles.

Interestingly, people considering transitions critical tend to expect action from all actors—government, businesses, and themselves. This diffuse sense of responsibility may not signal confusion but rather reflect an expectation of collaboration between these parties.

This nuanced perspective aligns with the nature of transitions, which are complex social processes. Ultimately, the interplay between behaviours across stakeholders and shifts in norms will drive these transitions forward.

The results make one clear: no actor—businesses, citizens, or the government—can afford to wait for others to take action first. For every transition, a significant group of Dutch citizens expects each stakeholder to take the initiative.

Conclusion 3: A Significant Gap Between Thinking and Doing

While respondents generally consider ecological transitions necessary, only a tiny group has fully adjusted their behaviour. For both the energy transition and resource use, many respondents indicate that they will only change their behaviour when the less ecologically harmful option becomes the cheapest when they are forced to do so or when no other alternatives remain. For instance, people are willing to buy locally or switch to green energy, but only if it becomes the most affordable option.

However, a notable minority (10–20%) plans to take action in the future for most behaviours—except giving up meat and dairy or relinquishing car ownership.

Well-being and social transitions present a more nuanced picture. Many people are already taking action, and a significant group intends to become more active. Additionally, many would adjust their behaviour if the government took more decisive steps to encourage the desired actions.

Conclusion 4: Citizens Alone Cannot Drive Transitions

While many people are already taking action across various transitions, the results show that even those who consider a transition necessary and see a role for consumers struggle to change their behaviour radically.

For example, among respondents who view 4 or 5 transitions as necessary—highly change-oriented individuals—90% believe that citizens should strive to reduce resource consumption. Sharing or renting a car is one way to achieve this. However, 30% of this group indicated they were unwilling to share a car, and another 20% said they would only do so if there were no other options. This demonstrates that even for those who acknowledge the necessity of transitions and expect action from citizens, specific changes in their own lives are far from automatic.

This highlights that individual consumer choices cannot fully account for successful transitions. Collaboration between the government, businesses, and the social environment is essential to achieve the necessary changes. To promote change effectively, government and corporate measures should be evaluated not only for their efficiency but also for their social acceptability.

Conclusion 5: Companies Alone Cannot Drive Transitions; Incentives (Including Pricing) Are Essential

Respondents expect companies to lead in reducing resource use and CO₂ emissions. There is less support for strong, directive government policies, and people often state that they will opt for the cheapest option regarding personal behaviour.

While companies have a critical role in reducing their resource consumption and CO₂ footprint, relying solely on businesses to act is unrealistic if consumers continue to prioritize the cheapest option and the government sticks to current policies. Many sustainable practices—such as designing longer-lasting products, ensuring repairability, or reducing emissions—are often not the most cost-effective options in the short term.

Just as it is unreasonable to place full responsibility for transitions on the individual choices of citizens, it is equally unrealistic to expect companies to solve these issues entirely on their own. However, as seen during the energy crisis, transitions can accelerate dramatically when sustainability becomes the cheapest option. To make the most sustainable choices, both affordable and unavoidable, normative policies or pricing mechanisms from the government are often necessary.

Conclusion 6: Tipping Points for Energy and Social Transitions Are Within Reach

The success of any transition depends on multiple parties and developments. For each transition, a significantly larger group of Dutch citizens favoured change than opposed it. This group of respondents, represented by the light blue diamond in Figure 4, supports change.

For every transition, a segment of the population is already taking significant steps to contribute to change, represented by the solid dark blue bar in Figure 4. The largest group actively engaged is in the CO₂ reduction transition, with 11% already taking action. The social transition follows closely, with 9% of the population actively participating. For both transitions, the critical mass of 25% needed to reach a tipping point is getting closer. This includes those planning to become more active, represented by the striped blue figure. When combining those already taking action with those planning to act, 22% of respondents are involved in the energy and social transitions.

Including people who would adjust their behaviour if it became advantageous or if many others in their social environment were to do so—those who are motivated by external factors and represented by the dotted bar in Figure 4—a substantial minority of over 25% of Dutch citizens are ready to take action. This means that tipping points for both the energy and social transitions are within reach.

The well-being and food transitions, however, are more complex. While the well-being transition enjoys considerable support, very few people are already taking significant action, and only a tiny group intends to do so. Together, these groups currently represent less than 15%, far below the critical mass of 25%. However, if we include respondents motivated by their surroundings or favourable prices, the 25% tipping point could still come into view relatively quickly. Achieving this, however, will require action from all stakeholders.

A tipping point in the resource transition is not yet within reach. Only pioneers are taking action, and only a tiny group intends to follow their lead. Even with pricing mechanisms, less than 25% of respondents indicated they would change their behaviour. This suggests that significant progress in the resource transition remains a challenge.

Conclusion 7: Resistance is Highest Among Middle-Aged People and Those with Lower Education Levels

Transition resistance is generally lowest among older adults over 65 and young people under 25. Resistance is more commonly found among middle-aged individuals. However, people over 55 are relatively active in taking steps themselves. Young people under 25 are less willing to take action than middle-aged individuals, likely because some actions are less accessible to them—for example, generating sustainable energy is only feasible for those who own a home.

There is also a clear difference in attitudes based on education level. Half of highly educated individuals support four or five transitions, compared to only a quarter of those with lower education levels. Highly educated individuals also take more action than those with lower education levels. Additionally, women are slightly more active than men in taking individual action.

Accelerating Transitions

Although the Dutch economy will probably be muddling in 2025, this research reveals significant underlying support for a major overhaul. The results offer reasons for optimism. Many Dutch citizens consider the five necessary transitions important, and many others are not vehemently opposed. This is likely due to an understanding that significant changes are essential for the Netherlands’ future prosperity, coupled with recognising that the country is at an impasse in several areas. This creates a foundation for collective action toward change.

According to this study, a key driver of progress is embracing the idea that change is necessary and desirable. Many citizens are already engaging with this notion. However, businesses and governments must explicitly acknowledge that change is inevitable for meaningful progress. They can rely on the large group of Dutch people who are quietly open to transformation.

The Role of Businesses

This means assessing whether their current activities will remain viable for businesses. Is their business model sustainable, knowing that a tipping point is near? Are the risks of becoming a "stranded asset" too great? What steps are necessary to stop greenhouse gas emissions and drastically reduce the use of primary resources? Does the company fit into a sustainable food system, and does it promote a healthy lifestyle?

For some companies, this may mean their existence is no longer viable. For many others, significant changes will be required in their operations, from resource and material use to the equitable distribution of benefits and costs among stakeholders. Sometimes, this necessitates short-term investments, but preparing for inevitable change is a sound strategy.

Entrepreneurs should also be encouraged by the demand for more sustainable and healthier products. Many consumers actively want this shift.

The Role of Government

The first significant step for the government is abandoning the idea that the current structure of society is sustainable. The Netherlands remains a country built on fossil fuels with an energy-intensive industrial base. Its economy relies on maximizing international trade through hubs like the Port of Rotterdam and Schiphol Airport, yet there is no credible plan to make this trade emission-free. Similarly, the Dutch government has long delayed action on unsustainable agricultural practices, lobbying in Brussels to extend outdated systems despite their apparent unsustainability.

Current policies perpetuate inequality, such as taxing labour more heavily than wealth, undermining social cohesion. These policies are out of step with public sentiment. This research shows that a compelling plan for change—one that includes everyone, strengthens social cohesion, and emphasizes healthy living—would likely receive broad public support.

Crucially, people need confidence that transitions will lead to a better future. While hesitation is understandable in the face of uncertainty, the uncomfortable truth is that failure to change threatens prosperity for future generations and the current one.

The survey results do not call for an overly interventionist government imposing high taxes on all "unsustainable" behaviours. For example, support for measures like a meat tax remains limited. However, there is widespread readiness to end policies that maintain the status quo, such as fossil fuel subsidies, VAT on second-hand goods, underfunded public transport, and weak enforcement of nitrogen limits in natural areas. Clarity on phasing out gasoline-powered cars, natural gas heating, and other unsustainable practices is also long overdue.

The government can play a pivotal role by ending resistance to change and presenting a hopeful vision for the future. The most critical step is to provide clarity on phase-out policies. This helps businesses adapt and gives citizens a clear sense of direction. With this clarity, the government can step back, allowing societal forces for change to flourish and enabling the market and society to find a new, more sustainable balance.

The Role of Citizens

For citizens contemplating change, the most significant potential lies in activating their networks. Both norm-setting and behavioural shifts are primarily social processes. Smoking in the Netherlands offers a good example: in the 1980s, most people considered it completely normal to smoke in public spaces. Today, even smokers often view it as a bad habit. As a result, the number of smokers has significantly decreased.

While people may not see their social circles as decisive in shaping their behaviour, research suggests that social norms play a crucial role. The survey results support this: respondents were grouped by "mentalities"—clusters based on shared worldviews. These mentalities often correlate with social networks, and respondents within the same mentality group gave similar answers about norms and behaviours. This underscores the importance of social environments in shaping norms and behaviour.

The call to action for all Dutch citizens who value sustainability transitions is clear: make your commitment known. Share your views with your friends, neighbours, local government, sports clubs, banks, the companies you buy from, and even strangers on the street. This is how social norms shift, and tipping points become closer.

If this momentum builds, 2025 could mark a significant step toward a sustainable Netherlands.

Thank you for sharing your outstanding report.

What if it's possible to design & create an extremely simple social tipping point -- usable by people everywhere for reversing the ecological crises as a whole -- that did not exist before? That's what I did in my mini-book, Simply Reversing the Eco-crises. Give it a look? https://erikkvam.com/simply-reversing-the-eco-crises/

Hello, Hans. I like this a lot; thank you. I publish a global warming newspaper online and wonder how you would feel about my reprinting some of it with you link. It's kind of long for what I do so I would use excerpts. Please email me your reply at ionaconner@pa.net. You can see my work at www.ionaconner.com if you're curious.