Dear reader,

Sometimes, life confronts you with stark contrasts. I'm doing well; my family is okay, and the weather is nice (although already too dry). And yet, the world around me feels like it’s unravelling. That contrast weighs on me.

Can I feel joy while also feeling deeply worried? Can I be full of energy and ideas, knowing—if I’m honest—that those ideas and energy likely have a limited impact on the things I worry about the most?

I suppose the answer is yes, and still, we go on—with all the doubts and hesitations—because not going on is not an option.

In the same spirit, my recent post on Collapsology sparked many responses. Many resonated with the core idea: that by understanding the mechanisms of collapse, we can better identify pathways toward a more livable, resilient world. System change remains a relevant concept—even when the system is on the brink of collapse.

This naturally leads us to the idea of tipping points. Once you start seeing them, you can’t unsee them. They’re everywhere.

In Het Financieele Dagblad, I wrote about the difference between positive and negative social tipping points. Two key insights stood out for me. First, while much of the literature focuses on positive tipping points—suggesting that just 20–25% of a population can drive systemic change—the same logic applies to negative shifts. A determined minority of that size can also destabilize institutions, societies, or entire democracies. We’ve seen this in various forms, from the erosion of trust in public institutions to the rise of populist movements. If we want to achieve positive social tipping points, the configuration of networks and strengths of relationships matter (below, I’ve expanded on that idea). Or, in plain language, it matters who we meet, what the relationships are, and how deep our conversations are. The stronger the network, the faster contagion goes.

Some readers reacted to my Collapsology post by saying it was "too negative." While I fully understand this reaction, I also wonder whether it reveals more about the receiver than about the message itself—though, admittedly, that's my own bias speaking.

For me, highlighting the gravity of our situation is not pessimistic; it's realistic, mainly when each passing week brings more evidence of inertia and delay. If you're deeply worried about our collective future, it shows, at the very least, that you care. The real danger lies not in facing brutal truths but in nihilism, in giving up entirely.

I've previously argued that caring about the future inherently involves hope. In his book Hope, Philip Blom suggests that at its most fundamental level, hope is the ability to continue living. However, we can only truly hope for a better future once we find meaning in it. And meaning itself is not rational, so hope, too, defies pure rationality.

Blom offers the example of marriage: statistically speaking, the chance of having a happy marriage might be very low (he cites just 6%). Yet many people choose to marry anyway, driven by the hope of being among the fortunate few. Such hope might not be rational, but we need it nonetheless because hope gives meaning to our lives.

Some brutal truths

So, I feel compelled to share a few more brutal truths from recent weeks—none more alarming for the global social fabric than what Trump sets in motion. His new trade tariffs—and China’s swift retaliation—aren’t just economic moves; they’re early tremors of a potentially more chaotic world order. Global trade has flaws, especially when built on extraction and imbalance. However, open economies and the free exchange of ideas have long been the backbone of global prosperity. The Trump administration, driven by a zero-sum worldview, seems intent on dismantling that foundation—one blow at a time.

Another brutal truth is the latest IEA report showing that global energy demand has accelerated in the past few weeks. While renewables are picking up, the overall picture is still one of addition, not transition. Fossil energy is not being replaced—it's being supplemented. We are not yet in the shift we keep talking about. And time, as always, is ticking.

This is the key figure (at the back of the report). The increase in renewable supply is insufficient to compensate for the rise in demand. And while the world has become more energy efficient, growth has still been higher. Jevons' paradox kicks in once again in real life.

Also, a new study in Nature shows that human impact on biodiversity loss is everywhere. Drawing on data from over 2,000 studies and nearly 100,000 sites, the researchers found widespread changes in species communities and declining local species diversity across land, freshwater and ocean ecosystems.

The findings highlight how complex and far-reaching human activity affects ecosystems.

The last brutal truth: Climate Change Will Erode Global Prosperity Far More Than We Realized. The assumption that climate change would only moderately affect economic growth (as was the conclusion in the widely used models of Economic Nobel Laureate Nordhaus) is quickly unravelling. Emerging research now reveals a far more severe economic toll than previously estimated—mainly because the models we’ve long relied on overlooked a crucial variable: our deep global interconnectedness. Climate disruptions in one region don’t remain local—they cascade through global supply chains, destabilize trade, trigger food insecurity, and stoke inflationary pressures far beyond their origin.

When researchers updated major climate-economy models to account for these global weather feedbacks, the projected losses in global GDP by 2100 under a high-emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5) spiked from 11% to a staggering 40%. In other words, our economic future is far more vulnerable than conventional models admit. Yet within this sobering outlook lies a clear signal: climate mitigation is not just an environmental responsibility but a prudent economic strategy. By curbing emissions aggressively, we safeguard ecosystems and preserve long-term prosperity, keeping global temperatures closer to 1.7°C rather than 2.7°C, and drastically reducing the financial fallout. The economic case for climate action has never been more straightforward or urgent.

Happiness and Benevolence

But, despite this unravelling, good news is always and everywhere to be found. In this case, the World Happiness Report is always intriguing (see for more on the content, see below).

In a world that often feels fractured and distrustful, one of the quietest yet most profound findings in the World Happiness Report 2025 is that we consistently underestimate the benevolence of others. This misjudgment doesn’t just distort our worldview—it makes us less happy.

Take the “wallet test,” a fascinating experiment cited in the report. When asked how likely it is that a lost wallet would be returned if found by a stranger, most assume the chances are slim. But real-world experiments tell a different story: wallets are returned far more often than expected in many countries, especially the Nordic region. In some cases, actual return rates are nearly twice as high as what people believe. Our pessimism about others' kindness is misplaced—and measurable.

This gap between expectation and reality matters. The report finds that simply believing others would return a lost wallet is a stronger predictor of happiness than even the absence of harm. Our perceptions of social trust and kindness carry as much emotional weight as tangible safety or wealth. And when those perceptions are overly bleak, our well-being suffers.

Benevolence doesn’t just help the recipient; it boosts the giver’s happiness, too. But perhaps most overlooked is how witnessing or even believing in everyday acts of kindness creates a powerful feedback loop—nurturing trust, reinforcing social bonds, and reducing the emotional burden of isolation or fear.

This insight is more than feel-good fluff. It’s a call to challenge our assumptions, to see the quiet good in others not as an exception, but as part of the social fabric. If we want happier societies, we don’t just need better institutions—we need better expectations of each other.

So, if there’s one clear takeaway, it’s this: benevolence, solidarity, and care aren’t just feel-good values—they’re fuel. They drive happiness, spark transitions, and help us reach social tipping points. They give people hope—as I saw firsthand during last week's presentation when a simple exercise revealed how deeply connection matters. So, let’s not wait. Let’s connect.

Below, for the very interested reader, the longer stories about social tipping points and benevolence.

How Do We Create Change When We Don’t Listen to Each Other?

Even in dark times, there’s hope for positive change. Major societal shifts often start slowly, almost imperceptibly—until they reach a tipping point and become irreversible. Technological breakthroughs such as renewable energy, artificial intelligence, or vaccines are frequently met with scepticism initially, only to reshape society in fundamental ways eventually. The same is true for social patterns. What begins as a fringe idea can swiftly become mainstream. Consider the Black Pete (Zwarte Piet) debate in the Netherlands: a once marginalised discussion is now largely resolved in the public sphere (we don’t have Black Pete anymore; we have Soot-Smudge Pete, which fits the story of coming down the chimney).

This phenomenon is known as a social tipping point. The concept originally comes from the natural sciences: coral reefs die off from pollution, and penguins migrate as the ice melts. Once a certain threshold is crossed, returning to the previous state is no longer possible. The same logic applies to societies. Think of #MeToo, smoking bans in public places, or the sudden social norm shift around "flight shame" in some circles. Change rarely moves in a straight line—it unfolds like a line of dominoes, where nothing seems to happen for a long time until everything collapses at once.

How Social Tipping Points Work

Social science research shows that change emerges from the interplay between behavioural choices and social norms. Behaviours that were once marginal gain traction as they become more affordable, accessible, or socially accepted. Take electric vehicles: once seen as a niche, hippie luxury, they’ve become a symbol of future mobility thanks to subsidies and rapid technological improvements.

These shifts are contagious. You're more likely to follow suit if you’re in a social group where vegetarianism is common. Social norm change is a kind of herd behaviour—not irrational, but an adaptation to evolving realities. The more cohesive the social group, the faster this behavioural tipping can occur. Surprisingly, most people aren't needed for this kind of shift: studies suggest that when about 25% of a population adopts a new behaviour or belief, a tipping point can be reached. The Pareto principle also seems to apply here: 80% of the effects may stem from 20% of the causes.

The contagion depends on the ties and the structure of the network

Recent research using hypergraph models, which capture complex interactions among groups, reveals that such contagion doesn't occur uniformly. Instead, it can exhibit multistability—situations where groups maintain multiple stable states simultaneously—or intermittency, where groups oscillate between low and high activity states. These phenomena occur particularly within community structures where interactions between groups (bridges) can trigger sudden widespread changes or maintain distinct pockets of resistance. Consequently, new ideas can spread rapidly through networked communities, creating cascading effects or remaining localised, causing competing norms to coexist and potentially prolong societal transitions. Understanding these dynamics provides critical insights for anticipating and managing rapid societal shifts or encouraging the adoption of beneficial norms.

Counterforces and Echo Chambers

This is the academic way of saying that every movement can unlock a countermovement, and successful norm change depends on interactions, strengths of ties, and rivalry in ideas. Entrenched interests fight back, especially when changes like Europe's green legislation become tangible. Polluting industries feel threatened, lobby intensively, and sow doubt. The paradox of transition is that success often provokes backlash: only once change begins to make a real impact does the resistance intensify.

This dynamic also helps explain the rise of negative social tipping points—regressive shifts where norms move backwards instead of forward. The Trump administration, for example, served as a political tipping point in the United States, not only reversing environmental regulations but also normalizing misinformation, polarization, and overt racism in public discourse. What was once fringe became part of the mainstream conversation. Similarly, the rise of far-right parties across Europe and anti-climate movements are symptoms of social contagion—but in a different direction. Norms do not inherently shift toward justice or sustainability; they can just as easily slide toward exclusion and regression when amplified within isolated bubbles.

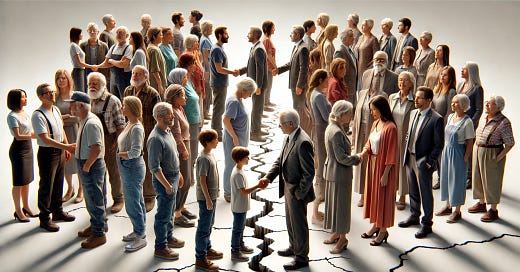

And herein lies another obstacle: social tipping only works when people encounter each other and engage in conversation. But our society is increasingly fragmented into digital and physical bubbles. Echo chambers reinforce one’s truths while economic segregation grows. According to the Netherlands Institute for Social Research (SCP), the contact between rich and poor steadily declines. Those who never leave their bubble will never be "infected" with new ideas.

Steering Tipping Points in the Right Direction

So, how do we ensure that social tipping points bend toward justice, sustainability, and solidarity? It starts with recognizing that most people want to change but often hesitates to take the first step. Climate change is widely acknowledged, yet habits and the perceived costs of adaptation remain barriers.

That’s why a subtle but powerful strategy is to make the sustainable choice easy. People tend to follow the path of least resistance. When sustainable options become the default—think of less packaging waste in supermarkets or trains being cheaper than flights—behavior shifts naturally. This is not coercion but design. Just as no one is forced to pay with a debit card, yet cash is disappearing from the streets.

Changing norms also requires inspiration. Transitions become tangible when role models and companies embrace the new normal. It helps when celebrities stop flaunting private jets and start celebrating night trains to Berlin instead.

Finally, we must actively seek connection during transitions. A small group can lead the way, but transformation only happens when ideas spread throughout society. So talk to the person next to you at your kid’s sports game, the gym, your neighbour, and especially those you randomly encounter walking the dog or doing groceries. And don’t just talk about the weather. We have to reweave the social fabric if we want to move forward together. That means talking about the hard stuff—the economy, the environment, and the future we want.

A social tipping point is like an avalanche: it seems insignificant initially, but once it starts rolling, it’s unstoppable. The real question is not if change will happen—but whether we’ll manage to steer it in the right direction.

Happiness and benevolence

Although the ranking is pretty stable, this year’s analysis added a lot to the social drivers of happiness.

A few noteworthy stories:

(1) Some rich countries (such as the US, Canada, and Switzerland) saw a significant drop in happiness over the last few years. The US dropped from place 11 to 24, with a .5 decline in overall happiness—quite significant. As former number 1, Switzerland saw its happiness decline even more (0.6), and Canada also saw a 0.6 drop.

(2) The familiar narratives often center on Western countries. But look a bit further down the rankings, and different, equally significant stories emerge. In 2013, Togo was the least happy country in the world. Since then, it has climbed 20 places, with its average life evaluation rising by nearly 1.4 points—one of the most remarkable improvements recorded. This upward shift reflects notable progress in governance and basic living conditions, offering a powerful counterpoint to narratives of stagnation in lower-income nations.

(3) In stark contrast, Afghanistan has seen the most severe decline in happiness over the same period. Its average life evaluation has plummeted by almost 2.7 points to just 1.36—the lowest score ever reported. The crisis is particularly acute for Afghan women, whose average life evaluation has dropped to an astonishingly low 1.16.

These two trajectories exemplify the more profound shifts within the global happiness landscape: a growing convergence in well-being across Europe, particularly with gains in Central and Eastern Europe, alongside steep declines in regions engulfed by conflict—and tentative gains where peace and stability have returned.

Each year, the World Happiness Report mirrors our collective well-being. The 2025 edition, however, feels particularly poignant not merely because it reiterates that the Nordic countries remain atop the happiness ladder but because of its thematic pivot: a deep dive into the social fabric that undergirds well-being—benevolence, solidarity, and connection.

This relates to the point I made above. Only connections can improve society, and benevolence—or the common good—is essential to individual happiness.

Benevolence is not just a moral nicety, the report insists. It is measurable, consequential, and—critically—unevenly distributed. Helping others, sharing meals, supporting family, and expecting kindness from strangers correlate strongly with happiness. But what stood out most was that our expectations of others’ kindness can shape our well-being more than actual harm or misfortune. This isn’t just a psychological quirk. It’s a systemic revelation.

Take the story of lost wallets. In experiments where researchers dropped wallets in the streets of various countries, the actual return rate was significantly higher than people had predicted. In other words, we systematically underestimate the benevolence of others. According to the report, this misjudgment has tangible effects: expecting kindness is nearly twice as predictive of happiness as the actual frequency of kind acts. Our cynicism makes us needlessly unhappy.

In Blog 19, I questioned the supremacy of GDP as a metric of societal success. In Blog 24 the message was that optimising well-being is not maximising the sum of each individual’s welfare, but to have a collective well-being, we also need to sacrifice something for the common good. Something we seemed to have forgotten. The World Happiness Report now affirms what many of us have long sensed: we thrive not alone, not through accumulation, but through mutual care. And yet, our economic models remain stubbornly rooted in individual utility maximization, blind to the dynamics of interdependence.

This is where Wilson and Snower’s multilevel paradigm becomes indispensable. They argue for an economics that integrates multiple levels of human behaviour—biological, psychological, social, and institutional—into its foundations. Instead of treating individuals as isolated agents, this paradigm recognizes us as embedded selves, shaped by our cultures, communities, and collective narratives.

From this lens, the findings of the Happiness Report are not marginal feel-good stories—they are core economic data. If prosocial behaviour reduces deaths of despair (as Chapter 6 shows), and if shared meals can rival income in predicting happiness (Chapter 3), policies that foster community and trust are not luxuries. They are growth strategies—though not of the GDP kind.

Perhaps it’s time to measure policy not by the speed of transactions or the scale of output but by its capacity to increase reciprocal trust, reduce loneliness, and elevate expectations of kindness. Perhaps our future depends not on how fast we grow but on how deeply we connect. Not coincidentally, this is also the best way to steer society towards a better, more inclusive, and sustainable state—to reach positive social tipping points.

Thanks for reading.

Take care and have hope,

Hans

Hans, I am so pleased I had the opportunity to read this nuanced, honest, and thoughtful contribution. I feel very affirmed: it is always wonderful to have one's sensemaking reinforced and, happily, deepened and extended. I have followed the Triodos bank for over 20 years and elevated it as a model where I can.

My writing and work have turned towards 'Islands of Coherence', motivated by reflecting on the collapse underway and conceptualizing how to think more coherently about responding to our predicament. Solutionism not only does not cut it; it is a false narrative. I am a practitioner and have been active (for 50 years) in community economic development, solidarity economy, resilience, resource management, and sustainable development spaces. I have written much over the years on these themes.

For the last 20 years, I have been reframing my thinking, work and perspectives. It is challenging, emotionally and spiritually. Today, the cascading impacts we talk about as the metacrisis make clear a humbling fact: human agency is irrelevant; the laws of physics are in play. What does this mean concerning where we put our energies? What is a strategic approach to consider this question, where we are living in a predicament without solutions, only responses?

If you are interested, I will happily share where my thinking is at. I think it might be a mutually interesting exchange. More about me at www.synergiainstitute.org

Thanks again for all you are doing.