Hi all,

We almost have a new cabinet here in the Netherlands. "Almost" because they still need to find the individuals who will take on the roles, including a prime minister, and they must delve into the details. This is a prelude to the European elections and reflects trends in other countries: a shift towards extremes, backlash against sustainability, populism, nostalgia for a past that never existed, and a conservative agenda.

If we examine the policy programme titled " Advocates for global isolationism – a surprising stance for a country that built its fortune on trade! It includes an extreme anti-migration agenda, significant support for the agricultural lobby (particularly powerful in the Netherlands), and reduced climate change ambitions. Additionally, the budget is based on weak foundations, such as plans to cut more than 20% of civil servant positions and reduce contributions to the EU, alongside legally dubious claims, whether under European law or Dutch law. In short, it consists of 26 pages of illusions.

But I think it does not matter for the biggest populist party, PVV. If they cannot execute the policies on migration or agriculture, they will point the finger at Brussels: ‘They are not willing”! A populist doom loop is in the making.

These policies mistakenly put two things at the core: self-interest and a false idea that we can return to the past. If everything were better, then these two things would be so against what we need to do: look at the future and how we can improve our future in times of polycrisis. We need to work together and understand our collective interests and influence, with all we have and what all we are, to achieve a positive future.

Self-interest drives people to do things as well as possible, to create products that people want to buy, leading to prosperity and progress. A society is the sum of all individuals. Thus, according to economists, collective prosperity is also essential. This individualistic view of humanity is seen everywhere: this is our neoliberal meritocracy, the idea that we succeed on our own and can keep everything or face misfortune and must deal with it ourselves. And this is what we see in the overdrive into neoliberal populism.

It has also become crystal clear that pursuing self-interest alone cannibalizes the collective. This article by Dennis Snower and David Sloan Wilson gives an excellent description of the difference between the individual ‘pursuit of happiness’ and collective well-being.

Self-interest is stronger than the collective within a group. Success for the individual insect, mammal, or reptile is a matter of success. However, at the level of society, altruism is needed between groups. Otherwise, self-interest cannibalizes cooperation, collective interests, and nature. This leads to inequality, the collapse of ecosystems, and polarization.

Something happened during the evolution of our species that resulted in a quantum jump of cooperativity. That “something” was in large part social control, meaning the capacity of members to reward the prosocial behaviors and punish the antisocial behaviors of other members. Our distant ancestors found ways of suppressing bullying and other forms of disruptive self-serving behaviors within small groups (Boehm, 1993, 1999, 2011). Increasingly, this is being studied as a form of self-domestication, similar to the domestication of our animal companions

(source: Wilson and Snower, 2024)

We seem to have forgotten this. Humanity's success depends on our ability to cooperate and offer each other something. That's what distinguishes us from other species. Our individual pursuits are embedded in society: sometimes, group norms restrict our aspirations for the group's success. A prosperous society is also embedded in nature: respecting planetary boundaries and regenerating nature—an embedded, restorative economy.

We don’t see that back in policy. While the urgency increases, the effects of Ecosystem Tipping Points might be disastrous—or, at least, huge (more on this paper below).

By now, almost everyone is aware of these collective problems. However, our reflex is to achieve this by seeking an ambitious job or adapting our lifestyle. The individual who ‘must make a difference’, individual morality. Conversely, those who want to make the world more sustainable are held accountable for unsustainable behaviour.

A fundamental misunderstanding. Our society is not made up of just individual 'I's; it consists of us in networks, communities, clubs, and like-minded groups. We are merely the smallest unit of the economic structure, embedded in social networks and based on nature. As fathers or mothers, we are children, citizens, neighbours, employees, entrepreneurs, consumers, employees, and voters. And in all these roles, we can influence others through our choices. But not only from our contributions. It is the shaping of social influence through groups in the different roles we have.

Understanding the difference between the individual and the collective is crucial to understanding what everyone can contribute. We can vote for a party that helps us realize our ideals. We can help others. We can take care of ourselves and our loved ones. We can try to realize dreams with others. And sometimes, we can also make a difference through our work if we have the luxury of choosing a job and not just trying to make ends meet.

That is also how we can solve climate change, for example, by doing things differently in all those roles until a critical mass becomes the new norm: a social tipping point.

We know that this is not going by itself. But the idea is that by ‘social norming’, society changes: you don't have to convince everyone to let, from then on, societal norms (peer effects) do the rest. There is also a tendency to overuse and overstate the idea. Recognizing and avoiding these patterns of “seeing the world through tipping point glasses” is important.

There is evidence that climate action can lead to tipping points (see here a post where I summarise two articles), but it is insufficient to trigger widespread adoption. Other factors, such as technology, infrastructure, and supportive policies, play pivotal roles. Once the tipping point is crossed, peer influences amplify the adoption rates, driving a self-sustaining loop of acceptance and further adoption.

Another question is what part of the population is needed. Of course, there is not one answer. Some people say it is 25% (referring to this research). Still, it depends on what part of the transition, the environment, the effectiveness of peer pressure, sustainable behaviour versus the use of technologies, etc.

It's not about what we do right or wrong as individuals. It's about doing things well together. And that can only happen if we occasionally subordinate our self-interest. And that starts with those who now have the luxury of more than enough.

But the crux is that everyone, in every role, can contribute. By what you buy. How much did you buy? What you vote for. For what you feel responsible in society. Which bank do you use, or how do you go on vacation? And it's certainly not just about individual action. It's about you as part of the system. By changing your consumer behaviour, you inspire others and expand the market for more sustainable products. However, by your voting behaviour or starting a care cooperative with others, you also help change the system, bringing tipping points closer. So it's always an interplay between changing the system, what the government does, the rules, norms, habits, and your behaviour. Only some people must or can lead the way. But everyone can contribute.

I don't think everyone can contribute equally to a better world, and I don't think everyone always makes the right choices. It's a misunderstanding to think everything starts with the individual. I often end up in discussions.

“Selfishness beats altruism within groups. Altruistic groups beat selfish groups. Everything else is commentary."

(source: Wilson and Wilson (2007)

Multilevel paradigm: embedded economy

The article "Rethinking the Theoretical Foundation of Economics I: The Multilevel Paradigm" by David Sloan Wilson and Dennis J. Snower, which I cited before, introduces a new approach to understanding economics called the "multilevel paradigm," which is based on generalized Darwinism. This framework seeks to address the limitations of traditional neoclassical economics by incorporating principles from evolutionary theory to explain better and tackle the complexities of economic systems.

Current economic theory, mainly following neoclassical economics, views the economy similarly to physics, focusing on individuals acting rationally. However, this view often fails to explain and solve many modern economic, political, social, and environmental problems. The multilevel paradigm, in contrast, uses Darwin's theory of evolution—not just in genetic terms but also in cultural contexts—emphasizing the processes of variation, selection, and replication.

One of the key strengths of this new paradigm is its integrative nature. While neoclassical economics typically focuses on the micro (individual) and macro (whole economy) levels, the multilevel paradigm includes a "meso" level, which encompasses groups of various sizes. This makes the approach more comprehensive and better suited to address real-world complexities and also gives more insights into transitions, tipping points, complexities and non-equilibria.

The article highlights how human cooperation has been essential for survival and economic success. Evolutionary theory provides insights into how cooperative behaviours develop and function. Specifically, Multilevel Selection (MLS) theory explains how traits beneficial to groups, not just individuals, can evolve by balancing self-interest with the common good.

A significant application of evolutionary principles in economics is functional organization. Just as biological systems must be organized to function effectively, so too must economic systems. This includes ensuring a fair distribution of resources, inclusive decision-making, and mechanisms to resolve conflicts. The article references Elinor Ostrom’s identification of core design principles (see below) that help groups manage shared resources effectively (polycentric governance), suggesting these principles can also apply to larger economic systems.

From those 8 principles (and their generalised version) they conclude three functions:

Define groups

Ensure effectiveness within groups by balancing individual and collective interests

Appropriate relations with other groups, reflecting the same Core Design Principles

Moving beyond neoclassical economics' limitations, the multilevel paradigm advocates for an embedded economy where economic processes are studied alongside political, social, and environmental processes. This holistic approach allows for a better understanding and more effective addressing issues like inequality, resource management, and sustainability.

If we come back to current politics and these design principles, we see that groups are currently defined differently: not at the level of a nation-state including future generations, but as a homogenous, native current population. Effectiveness within groups is not guarded since individual interests or (sub-) group rights (farmers, fossil fuel industry) are interpreted as absolute, not striking a balance between different interests. Also, regarding (3), there is no balance between various groups. Current politics is not polycentric governance. It is a populist-centric governance.

Ecosystem Tipping Points

Balancing individual and collective interests and having an embedded economy is key to achieving a better society. But how to get there and the urgency of getting there are other matters. I want to highlight one new paper on ecosystem tipping points and their potential consequences.

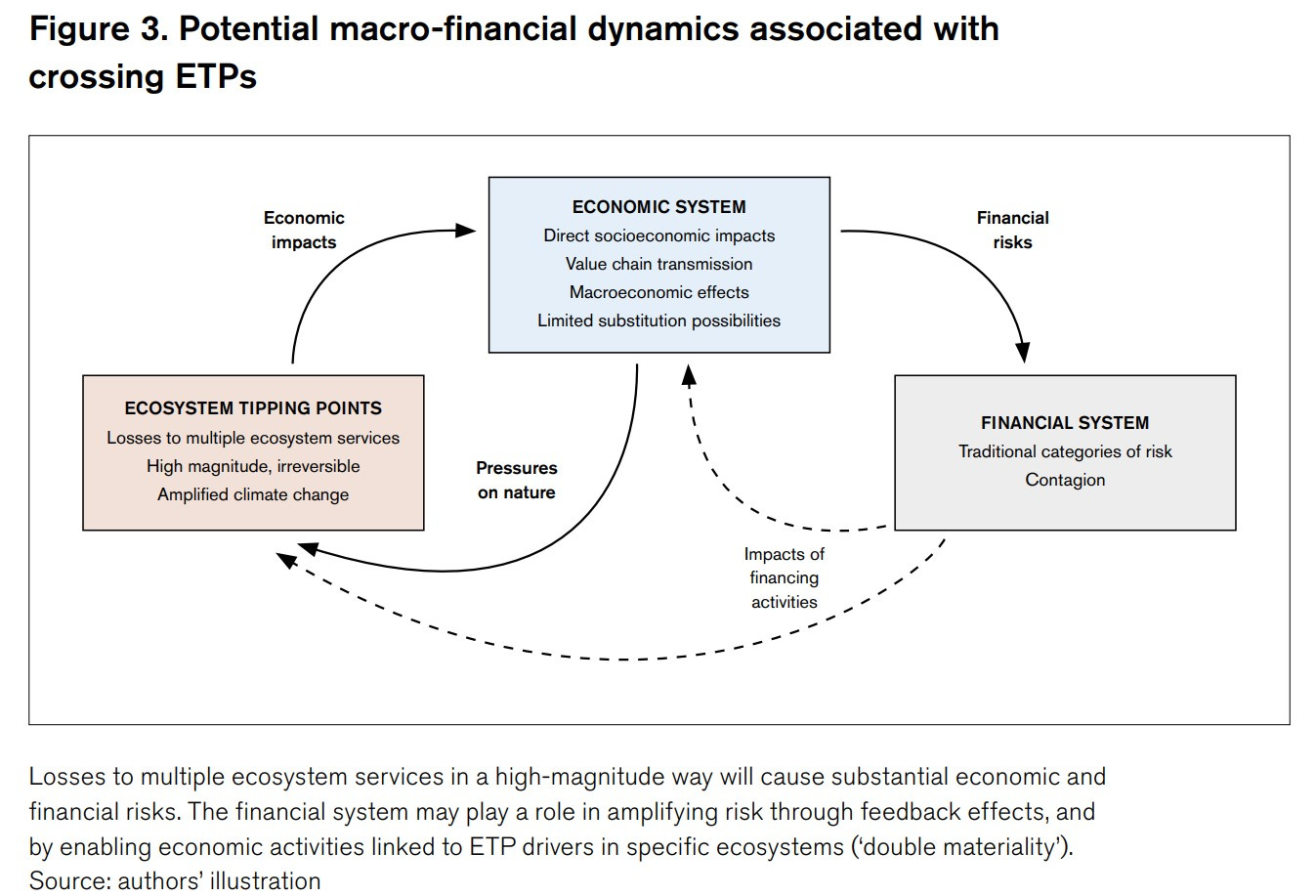

The report "Ecosystem Tipping Points: Understanding Risks to the Economy and Financial System" by Lydia Marsden, Josh Ryan-Collins, Jesse F. Abrams, and Timothy M. Lenton explains how critical changes in ecosystems (ecosystem tipping points, ETPs) can pose significant risks to the global economy and financial systems.

Natural ecosystems are crucial for economic activity. They provide essential resources, regulate the climate, and offer protection against natural disasters. However, human activities such as land use changes, pollution, and climate change are putting immense pressure on these ecosystems, increasing the risk of reaching ETPs. These tipping points represent rapid, large-scale, and often irreversible changes that can drastically alter ecosystems.

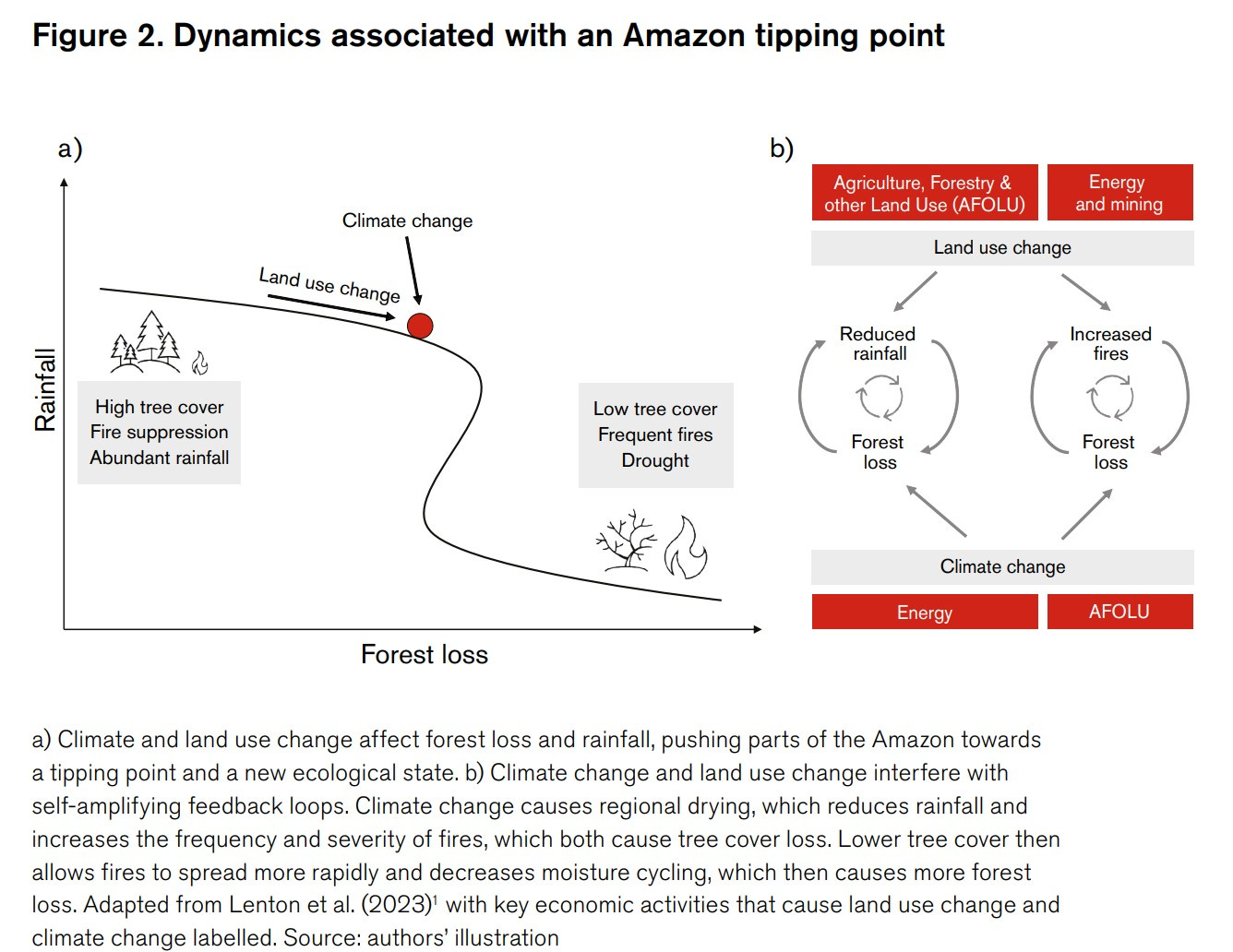

One significant tipping point involves the Amazon Rainforest. If the Amazon reaches a tipping point, large parts could collapse into a non-forested state, significantly reducing rainfall and increasing droughts. This would severely affect agriculture, water supply, and carbon storage (see figure).

Similarly, tropical peatlands in Southeast Asia and the Congo Basin store huge amounts of carbon. If they dry out due to land use changes or climate change, they could decompose rapidly, releasing massive amounts of carbon and becoming prone to fires.

Boreal forests in the northern regions are also vulnerable to rising temperatures. These forests could experience more fires and pest outbreaks, drastically changing their structure and function. Coral reefs face climate change and pollution threats, which can cause them to collapse into non-coral states, affecting marine biodiversity and the fishing industry. Rising sea levels and pollution threaten mangroves, which protect shorelines from storms and support fisheries.

These changes could release massive amounts of stored carbon, exacerbate global warming, and cause widespread damage to our economy through:

🔻 Reduced food and energy security

🔻Losses to real estate and infrastructure

🔻Increased health risks affecting productivity

Financially, the repercussions are systemic (and severely underestimated). They could lead to higher default rates, asset value declines, market volatility, and even inflation shocks, affecting global financial stability. Apart from direct risks (credit risk, market risks, underwriting risk) associated with physical due to ETP, there are transition risks (e.g. policies that protect nature that lead to stranded assets on balance sheets) and systemic economic risks. Feedback effects also exist between the macroeconomy and the financial system. For example, excessive speculation on commodity derivatives – financial products linked to food prices – can amplify food price volatility and become more prevalent during inflationary episodes. Again, it is all embedded.

Financial institutions and policymakers must urgently prioritize the risks associated with ecosystem tipping points. Innovative modelling approaches and a precautionary stance are crucial to prevent crossing these dangerous thresholds. While there is much we don’t know and cannot quantify, these uncertainties could have significant implications for well-being within our interconnected economy.

The potential for severe economic and financial disruptions underscores the necessity for urgent action. Research indicates that traditional economic models often underestimate the impacts of ecosystem degradation, failing to account for the complex interdependencies and nonlinearities inherent in natural systems. Innovative modelling approaches, such as multi-regional input-output models and better-parametrized damage functions, can accurately represent the economic impacts of crossing ecosystem tipping points.

Given the high uncertainty surrounding these tipping points, a precautionary stance is essential. The complex dynamics of ecosystems make precise predictions challenging, and the potential for irreversible changes requires proactive measures. Policymakers should focus on preventing the drivers of ecosystem degradation, such as land use changes and pollution, rather than attempting to predict the timing and outcomes of tipping points.

This approach aligns with sustainable finance principles, emphasizing the need for financial systems to support environmental sustainability and long-term economic stability. However, this is not what current sustainable finance practices are. Financial institutions and policymakers can help mitigate the potentially catastrophic impacts on natural environments and economic systems by prioritising these risks and adopting innovative and precautionary strategies.

That’s all for this week.

Be nice,

Hans