#8 The commons, the nation state and rivalry

How to govern the commons if we only think about individual interests?

Last week, I indulged in cycling, navigating the mountain bike trails close to my home. Like many enthusiasts of this pursuit, I maintain a Strava account to monitor my performance meticulously. Curiously, I often find myself compelled to juxtapose my current efforts against my personal best and the achievements of fellow cyclists. Naturally, while traversing the trails, the prospect of being overtaken, particularly by electric mountain bikes, is something I'm keen to avoid. It may seem trivial, but such inclinations are inherently human. Engaging in healthy competition is nothing to be ashamed of, especially when it pertains solely to self-improvement. After all, indulging in trivial pursuits is an integral aspect of the human experience.

Competition, a fundamental tenet of economics, catalyzes advancement and self-improvement. However, it veers into dangerous territory when it transforms into a relentless pursuit of one-upmanship, disregarding the broader societal good. This tendency is all too prevalent in economics, where the pursuit of individual utility often supersedes considerations of the common welfare—an egregious oversight.

Another pitfall arises when the concept of 'excellence' is construed in a relative context, with success measured solely in comparison to others, irrespective of the means employed. Regrettably, this myopic approach appears pervasive in the global economy, leading us down a path of mutual detriment—a lose-lose world scenario where everyone stands to lose due to cutthroat competition.

Competition can yield positive outcomes. However, the repercussions can be dire when it descends into unhealthy rivalry. The challenge lies in balancing fostering healthy competition and preventing its degeneration into destructive rivalry. I read three things this week on geopolitical stress, moral motives and well-being and the governance of the commons that got me thinking about all of this when doing my riding tours.

Ensuring the optimal governance structures are in place to safeguard collective interests, the planetary commons is one of the most pressing concerns, forming the focal point of this week's newsletter.

As always, at the end, some (other) news.

Enjoy.

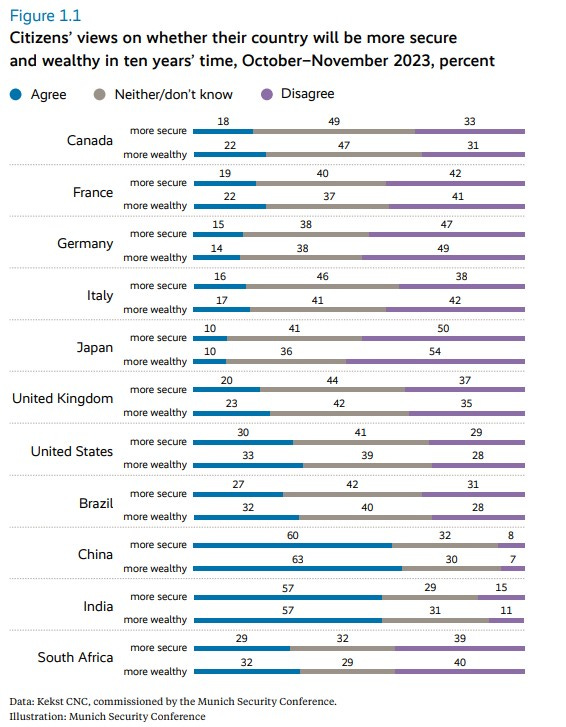

Disappointing National rivalry

According to the Munich Security Report 2024, we are entering a 𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐞-𝐥𝐨𝐬𝐞 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐥𝐝. Success is no longer measured in what you gain but if you lose less than others. It equals entering a different political era. The once bright outlook of the post-Cold War era, filled with geopolitical and economic optimism, has faded away. Citizens (especially in the wealthiest Western countries) are less optimistic about the future. Europeans are incredibly pessimistic, but American citizens no longer believe in the economic dream. Moreover, they expect China and other powers from the Global South to become much more potent in the next ten years while they see their own countries stagnate or decline.

In the face of escalating geopolitical tensions and economic uncertainties, influential players in the West, powerful autocracies, and nations in the Global South are increasingly concerned about their relative positions. Although these actions may seem logical given the shifting geopolitical landscape, they come at a cost, threatening the hard-won absolute gains achieved through global cooperation and risking a zero-sum world.

Greater economic security can mitigate conflict risks, but succumbing to relative gain thinking risks costly economic fragmentation, especially for Global South countries. This approach could remove mutual interdependencies, a key deterrent to aggression. The multilateral trade order is also at risk of becoming collateral damage.

In terms of risks, we see the same as in the Global Risk Report of WEF (see also my earlier newsletter on this)—a perception of increasing systemic risks from collapsing ecosystems and uncontrolled technology.

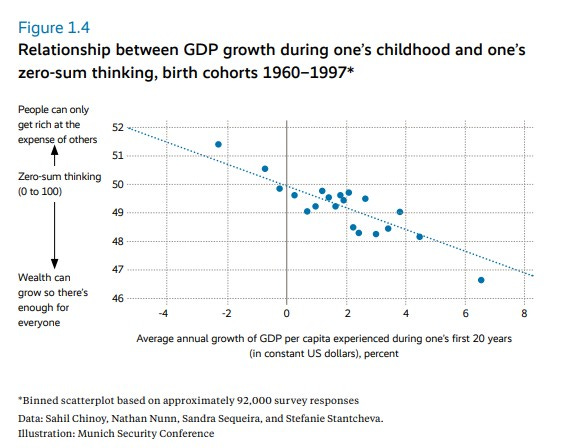

However, the prevailing emphasis on relative gains threatens the absolute gains achieved through global cooperation. But, if everyone is solely fixated on their portion of the pie instead of collaboratively baking a larger one, the overall size of the pie diminishes. Unfortunately, this mindset risks initiating a destructive cycle that could erode prosperity gains in numerous regions across the globe. The anticipated economic setbacks stemming from a "dangerous spiral into protectionism" will exacerbate internal trade-offs among various policy objectives. As national budgets contract, it becomes increasingly challenging to offset globalisation's adverse effects on those perceived as "losers," thereby making governments more attuned to relative gains. Moreover, the prolonged experience of sluggish economic growth among citizens fosters a zero-sum mentality. In its extreme manifestation, an obsession with relative gains could pave the way for a world governed by zero-sum beliefs – the erroneous belief that another party's gains inevitably translate into losses for oneself.

An ever-growing emphasis on relative gains in the economic field will likely also contribute to more significant geopolitical tensions and distrust. The risks are most evident in the military domain.

Since Trump threatened that if NATO members did not spend 2% of GDP on defence, they would not be protected from the US, defence spending will be an even bigger part of the budget of many countries from now on. This is relative gains par excellence...

What does this mean? First, we have entered an era of global fragmentation. That is what we see everywhere. Second, we need help with a shared understanding of well-being. Global or collective well-being is misunderstood as aggregating micro or nationwide interests—a sheer misunderstanding.

A wrong assessment of optimising wellbeing

The standard approach in economics is ‘micro-founded’ when we start with optimising well-being. Simply aggregating individual preferences will generate a collective preference and lead to optimisation once confronted with scarce resources. That is how macro models are built; we use macro figures like Gross Domestic Product or average household consumption as proxies for well-being. Theoretically elegant if you make the right (or the wrong) assumptions.

There is a lot to say about those assumptions, but only one for today: the belief that the sum of individual preferences yields optimal collective or societal well-being. It is utterly flawed if you ask scientists other than economists.

It is a well-known insight from anthropology, sociology and evolutionary science: one of the main drivers of human evolutionary success has been our capacity to cooperate beyond enlightened self-interest. This capacity has been shaped by moral motives throughout human development.

This idea aligns with multilevel cultural evolution, where rational self-interest can benefit within-group behaviour (as studied by economists). Still, prosocial behaviour (‘sacrificing’ one's interest) might be more beneficial for outcomes at higher social aggregation levels (as studied by sociologists). This effect is mediated through institutional setups, embedding social control mechanisms and symbolic thought (culture).

The current challenge is to accept that there are different moral approaches to well-being. Economists take a consequentialist approach (utilitarianism), where only outcomes count (how fast did I ride my MTB track). Another approach is deontological, where you do not look at outcomes, but the intent (did I enjoy my ride, no matter how fast or slow I drove and was it the right thing to do). Getting to a broader context of well-being, with room for other interests and different perceptions of what is important, requires a different moral mindset, similar to virtue ethics. One is meant to pursue multiple virtues, and the relevant virtues depend on our physical and cultural settings and our social roles within our social hierarchies. In my MTB riding example, it might have been better not to spend time on riding at all, but visit my mum or spend time with my kids (or do the laundry). The appropriate combination of moral principles can be learnt only through practice, following in the footsteps of moral exemplars. The recent paper of Fleurbaey et al. shows that it comes with a lot of moral dilemmas. From their conclusions:

It is commonly observed that economic and social decisions in our daily lives are riddled with moral dilemmas and it is common to feel the tug of conflicting moral demands. For example, should people be supported in accordance with their need or rewarded in accordance with their merit? How should we weigh the rights of individuals and communities in decisions on public infrastructure? To what degree should income be redistributed when redistribution hurts economic efficiency? Is theft condonable if the needs of the perpetrators are substantially greater than those of the victims? What are the moral limits of markets? Should we be able to sell our organs, pay mercenaries to fight our wars, transact pollution rights, sell citizenship to immigrants, pay for basic health care, and so on?

Mmm. This is a lot like the questions that you would like to be solved by politics. However, polarised political arenas are currently not the best place to solve these issues…

However, it is crucial to engage in this dialogue. With prevailing worldviews often leaning towards individualism and materialism, we tend to assess all actions – whether of individuals, groups, or nations – solely based on their immediate consequences. This narrow perspective leaves little room for recognizing common interests, let alone devising solutions for pressing global challenges like climate change, biodiversity loss, or the glaring disparities between the affluent global North and the impoverished global South. Instead of fostering a collective pursuit of well-being, this mindset perpetuates a downward spiral of relative rivalry. It's time to shift our focus towards uplifting collective well-being rather than getting caught up in individualistic pursuits.

Solutions for common Tragedy

There the last paper that I read this week comes in. This paper “The planetary commons: A new paradigm for safeguarding Earth- regulating systems in the Anthropocene”, essentially tries to come to solutions to the two challenges mentioned above: the lose-lose world and the absence of common interests. It challenges conventional notions of the global commons and advocates for a more expansive framework termed the "Planetary Commons", which confronts barriers of state sovereignty, self-determination, vested corporate interests, global power inequalities, and the complexities of demarcation that diverge from existing global commons and state borders.

The concept originates from the understanding that the current global commons—comprising the high seas, deep seabed, outer space, Antarctica, and, to a lesser extent, the atmosphere—have been negotiated by states within the context of the Holocene epoch. This negotiation primarily aimed to regulate resource access and usage, geopolitical interests, and environmental protection. These efforts were based on assumptions of a continuously stable Earth system, abundant resources capable of indefinitely sustaining life, and predictable and relatively minor environmental disruptions that humans could easily adapt to through incremental governance interventions.

However, the governance structures and the scope of what is governed must be revised. Consequently, the proposal advocates for a comprehensive approach encompassing all global commons and their tipping elements.

There a

re three challenges outlined in the paper:

The influence of entrenched interests and rivalry among nation-states.

It is overcoming the entrenched political trajectories, prioritising short-term national security and interests over a shared commitment to long-term planetary resilience.

It is establishing a moral value orientation that recognises 'commoning' as the most effective approach to achieving well-being for current and future generations.

The proposed solution involves adopting a nested earth system governance approach. At the highest level, there is a need for a comprehensive global institution tasked with overseeing the entire Earth system. This institution would be founded upon high-level principles and equipped with broad oversight and reporting mechanisms. The United Nations General Assembly, or a more specialised body mandated by the Assembly, could serve as the starting point for such an overarching body.

Furthermore, specific governance structures would be required for each key Earth system domain, including the atmosphere, hydrosphere, oceans, and cryosphere. While some of these structures may be based on existing frameworks, others would need to be developed anew to address the unique challenges of each sphere.

A quote:

The planetary commons will require moving away from global commons as a means of governing resource use of natural resources beyond national borders, to universal rules of how to collectively secure critical biophysical Earth system functions that regulate livability on Earth for everyone, irrespective of where these functions are located. We believe that the planetary commons framework has the potential to initiate the long overdue paradigm shift that we urgently need to safeguard the Earth system as we move deeper into the Anthropocene.

It will be a challenge. Not (only) politics but also mindsets. To end with good news, there are more people than we might think that are willing to pay for the environment. Willingness to pay is maybe a first step to accepting that global interests sometimes offer from individuals…

In the news

Tipping points: Atlantic Ocean circulation nearing ‘devastating’ tipping point, and up to half of the Amazon rainforest could hit a tipping point by 2050.

Trust in science is relatively high:People worldwide have high levels of trust in scientists, and most want researchers to get more involved in policymaking. However, trust levels are influenced by political orientation and differ among nations. And this relationship is not straightforward. In some countries, right-wing parties are sceptical about science. In others, left-wing parties.

Insurance market doom loop: A surge in losses and soaring costs of reinsuring property. And when risks become too high, homeowners can find themselves uninsurable (see also here my post on it.

Recessions have a positive effect on life expectancy: An NBER shows that economic growth and recessions have more nuanced effects than commonly portrayed. Recession-induced mortality declines are driven primarily by external effects of reduced aggregate economic activity on mortality, and recession-induced reductions in air pollution appear to be a quantitatively important mechanism.This can be broadened. When economic growth is at the cost of already overstressed ecosystems, it can hardly be called beneficial.

That’s all for this week.

Take care.

Hans

Hans,

I've only read a few of your posts as I'm new to this blog. So far there has been no mention of the biological scale of our species compared to the rest of life and the finite resources on the planet. We grow ~ 200,000 daily, and have doubled in your lifetime, tripled in mine, and quadrupled in my mother's 97 years. Why do you focus on attempting to alter behavior of individuals as the best approach to reaching sustainability?

The vast majority of scientists and philosophers are determinists, with our embodied physical history including heredity (not just genes) and the present circumstance the drivers of behavior. Voluntary simplicity is a tiny tail on the Bell Curve. Techno-optimism seeks design solutions. Cultural change can help. But in overshoot, treating the symptoms can't cure the disease.