#7 Cynical finance anti-wokeishness

Why every good seems to turn into something bad

Hi all,

If there's any industry where cynicism runs deep within its culture, it's finance. Here, the paramount concern isn't how returns are generated but whether they're made swiftly. Every discussion about global crises, politics, or sustainability is met with the same refrain: "What's the business case? What does the DCF model suggest?". Everything is calculated and brought back to individual gains. Wider considerations such as impact and risks are routinely reduced to familiar financial metrics, with scant regard for their ethical or moral implications. And if it cannot be measured, it simply does not exist.

Some may perceive this attitude as a relic of a bygone era, but I must dispel that notion—it persists today. Some individuals have seen remarkable success in recent years, often challenging traditional finance with disdain and branding it as "woke". The ESG backlash is cynical finance anti-wokeishness. The dominance of the underlying worldview is dangerous and destroying our future. Therefore, it's crucial to acknowledge the cynical investor, understand their tactics, and recognise their influence.

The use of discount rates and the divestment/engagement debate are two areas where cynicists still have strong positions. It helps to navigate the mindset of the cynical investor. After all, they're not faceless entities but individuals with lives, families, friends. If we all realise that markets are imperfect, influenced by normative investors and outcomes should be judged holistically, we might have a valuable discussion between cynical finance and woke finance. If it is not for a common interest, it is at least their own future life. And let’s not forget the most cynical persons are often disappointed idealists.

In the end, you’ll find some news.

Enjoy

What do you do when you are cynical?

“A cynic is a man who knows the price of everything but the value of nothing”. This famous quote of Oscar Wilde captures the essence of how cynics see finance. Cynicism is a mindset or attitude characterized by distrust, skepticism, and a belief that people are motivated purely by self-interest. Cynical individuals often view human actions and motives with suspicion, doubting the sincerity or altruism behind them. Cynical implies having a sneering disbelief in sincerity or integrity.

A cynical investor can be described as someone who approaches financial markets and investment opportunities with a deeply sceptical and distrustful mindset. Instead of viewing investments as opportunities for growth or contributing to societal benefit, a cynical investor may see them solely as avenues for personal gain, often exploiting loopholes (hey, it is possible and not forbidden), disregarding ethics (again: if it is not forbidden and you can make a return, why not), and prioritizing short-term profits over long-term sustainability.

If you are cynical:

You never divest if it hurts performance: There are good reasons to divest. But they are only financial. So, you come up with

You only engage with companies about topics that are of material interest and if the cost of engagement is lower than the expected return.

You will always concentrate on the short run (that is what matters to your clients most).

You invest in those companies with ‘a moat’: The term “economic moat,” derived from the water-filled trenches that surrounded medieval castles to protect them from invaders, is a key concept in star investor Warren Buffett's investment philosophy. It refers to a business's ability to maintain a competitive edge and protect its market share and profitability from rival firms. Economists would call this monopolies. And too much market power hurts societal well-being.

You will only do sustainable finance if it is a separate client group, helps diversify (uncorrelated returns), or has superior (expected!!!) risk-return profiles.

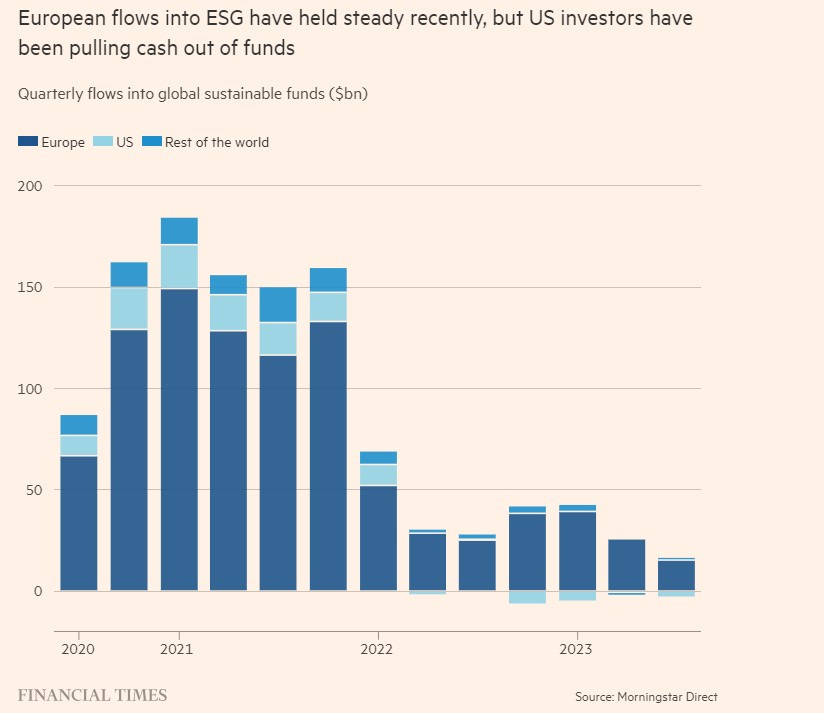

But you will never, never give up any returns. That is why we see ESG investments having lower inflows and meeting less enthusiasm: since the Ukraine war, weapons, fossil fuels and other non-sustainable stuff simply have higher short-term returns. There are more cynical investors than you think.

You will never, never, never make ethical choices. Morality is for those who think there are other considerations than self-interest. And that is a different world than the world of the cynical investor.

The role of discounting the future

This ethical perspective starts, and people tend to forget it, with choosing the appropriate discount rate.

I was reading the (great and also depressing) book ‘Ministry for the Future’ by Kim Stanley Robinson. He has an excellent discussion among his characters in the Ministry about the discount rate. This is more or less as he also answers in this interview:

“The discount rate is simply picked out of a hat, but it has enormous consequences. Even your standard economists will admit the higher the discount rate, the less you value the people of the future, the lower the discount rate, which could go right to zero, the more the future generations are treated equally to us in economic calculation. The reason that economics doesn’t have a zero discount rate is that there’s going to be many billions of future humans. So, if their rights to our behavior are the equal to our own, then we should be doing everything for them and nothing for ourselves. So a discount rate gets applied. Famously, Nordhaus won the pseudo Nobel Prize for suggesting a four percent discount rate, which is really way too high if you want to treat the future generations as worthy of our consideration and action in the real world now.

I don’t know how he defended it but I suspect it gets technical in ways that I couldn’t follow. There are many economists that would say a discount rate of zero is perfectly appropriate. There’s also the case that it doesn’t have to be linear forever. I’ve heard it both ways. This is a very interesting economic debate that I can’t enter into. Should the discount rate be zero for the seven generations to come and then rise and get sharper so that you reduce the infinity effect? Or, should the discount rate be kind of high now and bell curve off into zero after seven generations? The seven generations is just a term out of Indian philosophy and ethics, saying that the way to treat the intergenerational issues is to consider the seven generations before and after you as being like sacred ancestors and descendants who have to be treated as if they were your immediate family. That runs it off a couple of hundred years in each direction.”

This is not the discussion of (cynical) investors. Just apply the (current) market rates for current futures because Mr. Market is right! It is another way of taking responsibility away from a person who makes the decision and hides between abstract notions and real-world consequences.

Because what you discount and how you discount matter a lot, for some investments, a high discount rate might be excellent: when depreciation rates are high, and there are no longer-term consequences for society, why not? In other cases, e.g. when ecological changes are irreversible and damaging, discount rates might even have to be negative: it will cost extra money in the future to restore society as it was before.

There is absolutely no consensus among policymakers and economists on the best or optimal discount rate (see also this post by my colleague Ernst about the social costs of carbon).

The consequences are enormous. Not considering the ‘time value of money’ is often inconsistent with sustainability. No problem for the cynical investor.

The divesting/engagement/voting arguments

Another example pertains to the debate surrounding the efficacy of engagement versus divestment as strategies to expedite the transition toward a more sustainable world. Advocates of engagement, who advocate for remaining invested in a company rather than divesting shares and instead pushing for change from within, consistently present familiar arguments. They argue that divestment merely results in another party acquiring the shares, thus having no impact on the cost of capital. Conversely, staying invested allows for the exertion of influence through avenues such as voting and engagement. Therefore, proponents argue that divestment or exclusion yields no tangible outcomes, while engagement stands as the preferred course of action.

This literature review of Auke Plantinga and Bert Scholtens shows rather straightforward that:

🔷 Justification for divestment is readily apparent, primarily grounded in moral and ethical considerations.

🔷 The financial impact of divestment is generally limited at the company, industry, and macro levels. So far, divestment has not significantly curbed carbon emissions.

🔷 In addition to divestment, investors can wield their voting rights to steer fossil fuel firms in a different direction or engage with the firm's leaders. Yet, there's no evidence proving the effectiveness of these actions in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

So, divesting can not easily be justified based on superior (short-term) returns. Although the debate is going on.

Furthermore, demonstrating tangible results from company engagement poses a challenge (as evidenced by this kind of research). Establishing causality is complex (as an investor, you may engage on an issue, but you may not be the sole investor or stakeholder exerting pressure on a firm regarding that issue), and effecting meaningful change can span years, extending beyond the horizon of cynical investors. In particular, engagement aimed at altering the core of a business model (e.g., fossil fuel companies, fast fashion) proves difficult and often unsuccessful.

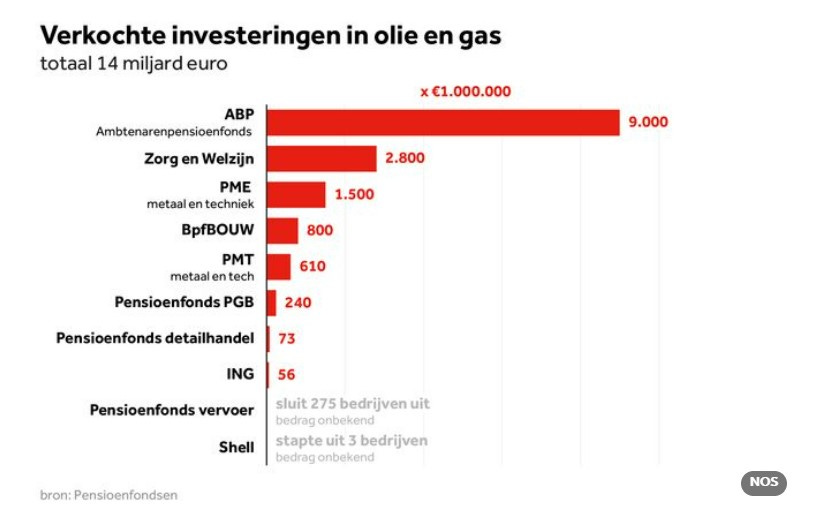

Consequently, many Dutch pension funds have reached a decision: They have divested from fossil fuel companies.

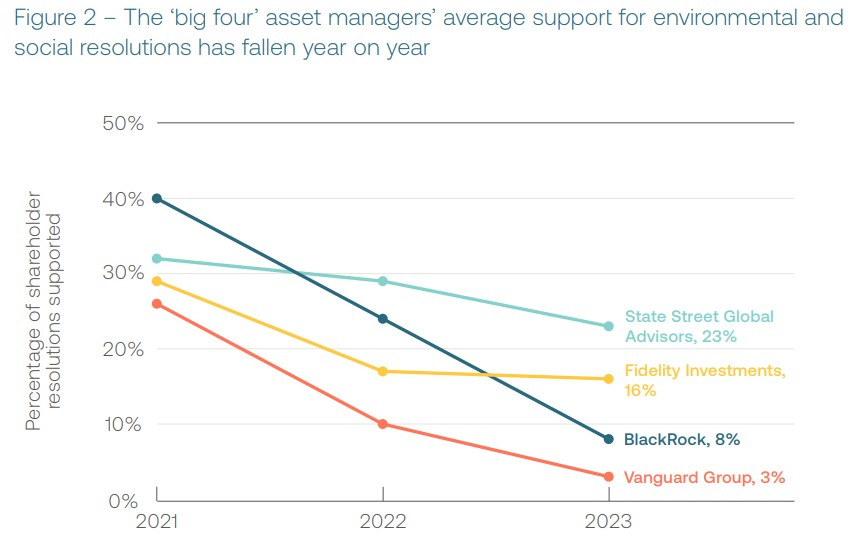

So, what about that voting behaviour? Not so much to be enthusiastic about, as this he ShareAction report clearly showed. Shareholders do not powerfully bring sustainable change to companies. The support for shareholder resolutions peaked in 2021 but took a nosedive in 2022 and 2023 (hurray cynicists!). In the latter year, a meagre 3% of evaluated resolutions saw the light of approval, with only eight out of 257 resolutions cutting. This marks a significant decline from the 21% approval rate observed in 2021. The heavyweight champions of the financial realm, the 'big four' asset managers (BlackRock, Vanguard, Fidelity Investments, and State Street Global Advisors), bear the brunt of blame for this backslide. In 2023, on average, they threw their support behind a mere one-eighth of the proposed resolutions—starkly contrasting their more generous backing in 2021. The performance of US asset managers, in particular, is nothing to write home about. On average, they lent their support to just a quarter of resolutions. Amidst all this, the shadow of greenwashing persists in lofty promises but little action.

That's the global scenario. Thanks to legislation, European asset managers boast a better score, with an impressive 88% of resolutions passing. But also there, given Exxon's actions to bring investors to the court that are trying to vote for more sustainable policies, “wokeishners” are losing from cynicism.

However, the genuine concern lies in the reluctance of US asset managers to tackle ESG issues in their voting practices. Unsurprisingly, the largest asset managers perform like is expected from ‘standard’ investors: fiduciary duty, right? Foremost defined in risk-return language with mandates a little sustainability sauce to silence people who care about the future. This poses a threat to the sustainable trajectory of companies. With upcoming elections globally, the likelihood of regulatory forces steering capital toward a more sustainable path seems dim.

In the short term, within the parameters set by the rules set by what we think is normal in finance (encompassing discount rates, risk assessment methodologies, and interpretations of fiduciary duties), the stance of the cynical investor mirrors that of the average investor. Speaking of cynicism...

One potential solution is altering the rules. However, the pervasive influence of anti-wokeness, exemplified in this column by my colleague Joeri, presents a formidable obstacle to amending regulations supporting more sustainable outcomes. This represents the massive lobbying efforts of vested interests, contending that financial markets ought not to be normative. Yet, this argument holds water only if markets are truly neutral, which, in reality, they are not.

The solution: Address the disappointed idealist

Regardless of their level of cynicism, investors often fall into similar error patterns: they are reductionist, confuse market outcomes with market neutrality and assume efficient markets.

First, they adopt a reductionist viewpoint, failing to acknowledge systemic risks and issues.They only consider outside-in and not inside-out risks.1 Consider, for example, the discourse surrounding ESG risks prompted by regulators and central banks: it predominantly revolves around the impact of external forces on investments, neglecting the reciprocal relationship. While this approach may sidestep ethical debates, it also serves to disregard systemic issues—a classic misstep. To adequately address systemic risks within one's portfolio, it's essential to adopt a holistic perspective on climate, biodiversity, and social risks, while also scrutinizing one's own role. For the cynical investor, it should be immaterial whether the threat arises from climate change-induced disruptions in the supply chain of an agricultural company or from internal mismanagement or competition. Both scenarios demand action or reaction.

Secondly, most investors pretend that they are apolitical. They are not. Their political views colour investors’ economic outlook, as this paper shows. They showed that likely-Republicans increased the equity share and market beta of their portfolios following the 2016 presidential election, while likely-Democrats rebalanced into safe assets. They have also found that their willingness to take on financial risk depends on how their views align with the government's. The composition of investors’ stock holdings differs according to political opinions according to this paper. Researchers found evidence for a causal effect of political differences and showed that the effect of political differences on portfolio differences operates mainly through diverging political views on social and environmental issues rather than differences in economic expectations.

Conclusion: all ‘rational’ choices of financial markets are based on their own normative assumption. Self-interest is a normative assumption which is definitely not neutral.

This brings us logically to the last point: markets are not efficient. Every investor knows that. There was no room for (excess) profits if they were perfectly efficient. There wasn't a need for analysts. There was no use in doing any research. Hence, since markets are imperfect, outcomes are also not neutral but depend on the norms and assumptions of all actors.

And here is the bridge between our cynical investors and woke, sustainable investors (like myself). If you acknowledge that you are normative, that reductionism is not in your own interest and understand that markets are not perfect, it might be easier to see that there is only one difference between the value-driven, normative, woke-ish investor and the cynical one: the first one has hope for a better world, the other not.

That might be a valuable discussion.

“Scratch any cynic and you will find a disappointed idealist.”

― George Carlin

In the news

Carbon Dioxide Removal as a reductionist problem: In this article, (behind paywall), the authors highlight the persistence of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) as a crucial component to achieve the Paris Agreement goals, entrenched in nearly all IPCC mitigation pathways. However, the predominant focus on land-based CDR in many IPCC pathways raises concerns regarding sustainability, potentially jeopardizing human livelihoods and food security. The IPCC report lacks a comprehensive evaluation of these scenarios' environmental feasibility and associated sustainability risks. Moreover, it fails to quantify the scale of deployable CDR without triggering significant impacts.

According to this study, nature-based solutions emerge as the least risky option, yet the allowable risk budget is smaller than assumed by the IPCC report.Is AI really the biggest threat when our world is guided more by human stupidity: column for Nouriel Roubini (not the most optimistic guy of course). It's crucial to remember that human ignorance often outweighs the influence of AI in our world.

That’s all for this week.

Take care.

Hans

Inside-out risks are those effects that are caused by investments to the outside world, and outside-in risks are those that appear in the outside world and are (materially) influencing the (financial) value of an investment.

How can we leverage the acknowledgment of these normative assumptions, the recognition of market inefficiencies you’ve mentioned, and the imperative for holistic risk assessment to redefine investment paradigms in the energy transition space so as to drive de-growth towards a steady state economy?