#5 Can business be sustainable?

A core question about the system with a complicated answer

Hi all,

There are various perspectives on businesses. One, as frequently portrayed in the news, depicts them as the source of all evil—profit-maximising, society-destroying machines that perpetuate inequality, manipulate politics, and exploit employees. Undoubtedly, this view has some truth, although some may argue that society and consumers also share responsibility.

However, the moral question is not our primary focus this weekend. Instead, I aim to explore whether businesses can adopt a more sustainable, positive role—a catalyst for change, regenerative, and operating within planetary boundaries. And if so, under what circumstances is this most likely? Is having a sustainability report and a net-zero pledge sufficient, or does obtaining B Corp certification make a difference? To distil it down to one of the central questions: can sustainable business coexist with the profit motive? These are fundamental inquiries, and I hope my tentative answers assist you in forming your own conclusions.

To wrap up this edition, here are some links and highlights from the past week.

Please stay in the loop by subscribing directly or joining us on Substack.

Enjoy

Detrimental business

The question of who bears responsibility for causing harm is a matter of attribution in a society that is detrimental to nature and a significant portion of its members. If the system is detrimental in itself, it is not the system that is guilty, but some parts of it, or their interaction. In a very superficial analysis, one could argue that the end-consumer contributes to pollution. That implies us—those who drive cars, purchase clothing, and consume food. If we persist in acquiring environmentally harmful products, it is our error. Therefore, we should refrain from blaming businesses or attributing responsibility solely to the most polluting sectors, such as fossil fuel production and heavy industry.

This is the viewpoint of for instance oil company Exxon Mobil, who sues Follow this to block a vote on a climate resolution brought by the green activists, in move that will be watched closely by fossil fuel companies worldwide.

The company hopes to stop investors voting on a motion by Follow This, which called for Exxon to accelerate its attempts to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

You could also follow the classic Friedman doctrine published in 1970, where Milton Friedman explains why:

“There is one and only one social responsibility of business--to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it stays within the rules of the game, which is to say, engages in open and free competition without deception or fraud”

In other words, consumers nor companies are to blame if the system does not deliver sustainability, it depends on the ‘rules of the game’. If they allow companies to behave unsustainably, it is a political responsibility.

This is, luckily, not consensus. Most companies agree that they should produce things more sustainable. Therefore, many have climate pledges, sustainability reports and programs to produce the negative effects of business.

So, let’s for a moment conclude that, although clients buy stuff that is not sustainably produced, it are companies who do the action, have the best insights into the detrimental effects of production and, that is the most important aspect, also make profit at the expense of environment or human rights.

And the figures are not so positive. For instance, if companies had to pay for the problems their carbon emissions cause, their profits would plunge, possibly wiping out trillions in financial gains. These results, spelled out in a recent study in the journal Science, are based on analysis of almost 15,000 publicly-traded companies around the world.

For all of those companies combined, the damage would run into the trillions of dollar. The researchers only included direct emissions from companies, not “downstream” emissions related to the products they sell. (So emissions from the operations needed to build cars would count; the pollution that comes out of its tailpipe wouldn’t.)

They found that the cost of damage surpassed profits for highly polluting industries, including energy, utilities, transportation, and materials manufacturers — a group that accounted for 89 percent of the total. On average, it would mean that 44% of their profits would be wiped out.

But this is only carbon. Taking other ‘externalities’ (non-priced effects of economic actions) into account, the effects would be even bigger. A study from the Dutch Central Bank, calculating the effects of 30 environmental externalities, showed that total environmental damage costs associated with the Dutch economy amount to EUR 50 Bn or 7.3% of Dutch GDP in 2015. They also demonstrate that some sectors (energy production, waste and sewage treatment, manufacturing, transport and agriculture) do not generate sufficient profit to cover their natural resource use and pollution costs. And then we haven’t seen all negative side-effects, because we simply do not have the accurate data.

The implementation of new regulation, like the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) will give more insights in the detrimental effects of economic activities in Europe, and will help to show the damage done.

Better business

Okay, as a first step we know that business is, in general, not sustainable. In other words, probably a lot of companies destroy societal value instead of creating it. And, as a interim conclusion, if that is the case, it is impossible to speak about ‘sustainable business’. So oil companies with a promise to become net zero are currently still destroying livelihoods; agricultural or manufacturing companies that at the moment are ‘net’negative, can never be called sustainable.

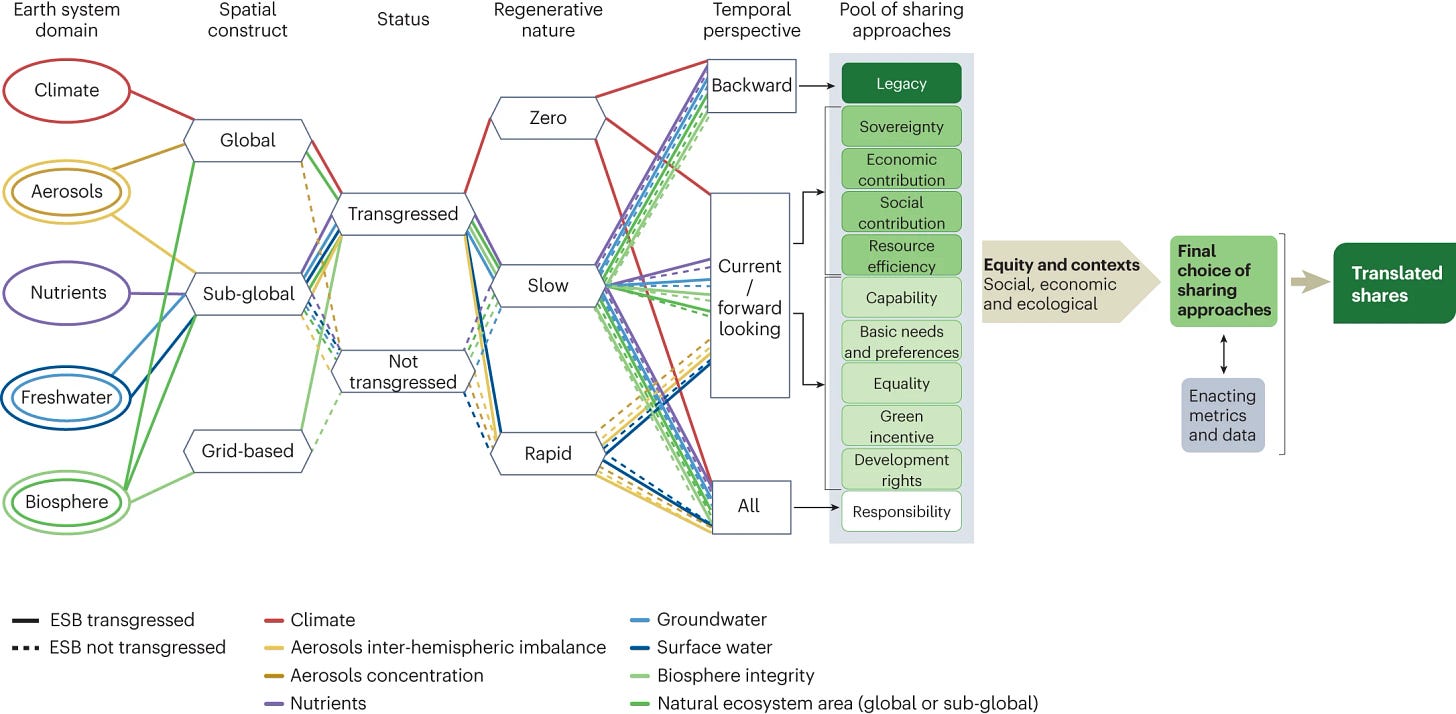

Especially on the ecological side, this discussion is getting on an interesting path. For example, the recent research on translating Earth system boundaries (ESB) for cities and businesses, shows the way forward, but also the complexities related to that.

Look for example at a figure from their text below. Key decision points in ESB cross-scale translation pertaining to the Earth system domain, spatial construct of the boundary, the current status of the boundary, the regenerative nature of the boundary on policy-relevant timescales and applicable temporal perspective for sharing. These aspects can guide towards a pool of sharing approaches (shown in different green shades) from which an actor can choose followed by considerations of equity and actor’s specific contexts, as well as choice of enacting metrics informed by available data, before arriving at the final choice of sharing approaches. Applying the final set of sharing approaches would produce allocated shares for the respective Earth system domains.

A more responsible approach to business should consider all these aspects. However, before diving into the discussion: who is responsible for taking all of this into account? Is it still something that only policymakers should impose on businesses? And how on earth is that achievable? Simply pricing externalities and setting norms might not be sufficient; it is a more intricate matter.

Consider the green area on the spectrum of sharing approaches: this involves a values-based discussion at the company level. It becomes significant whether the share allocated to a company is based on legacy (shares proportionate to current or historical entitlements, ecological impacts, or environmental footprints generated by the entity - also referred to as grandfathering), implying that the most polluting companies bear the most responsibility to reduce. Alternatively, it could be based on a social contribution (shares allocated in proportion to the current contribution of the sector, industry, or company to communities and wider society, for example, measured in numbers of people employed). The article discusses 11 such sharing approaches. This is an ethical, some might call it political, but certainly a subjective matter. In other words, determining a 'fair share' on a company level is challenging.

Governing better business.

Is it then impossible to say something about better, sustainable or restorative business? Of course there is. But hardly to do at the outcome level. We must restrict ourselves to governance and intentions. And then we end up with numerous ideas. New business models have emerged that attempt to place business on an ecologically healthy footing. The doughnut economy, the economy for the common good, restorative business, sufficiency enterprises, B corps and postgrowth and degrowth businesses: These and other experiments represent ways of doing business that not only create customer and firm value, but address social and environmental needs as well, where the question remains open if it is good enough. In a context of scarce resources and the necessity to get smaller fair share (in whatever way calculated), such experiments are excellent vehicles for providing the goods and services people need, within boundaries set by nature.

The image below summarises some of the ideas (from this paper) in terms of business models: sustainable, circular and regenerative businesses.

Although it shows the myriad of approaches taken, it does not define if all these approaches will help to make our world better. I still think it is in the main structures of businesses in terms of governance, not only in their product design, supply chain management or production. I see three main elements determining sustainable outcomes: relationship with profits, ownership structures and responsibility to all stakeholders.

The relationship with profit is crucial, as Jennifer Hinton succinctly points out. The more profit required to satisfy the owners, the stronger the incentive for businesses to expand their operations, increase turnover, and maximise their profits. This connection is closely tied to the company's purpose, as defined in its articles of association.

For instance, certified B-corps typically excel in their objectives, as do businesses that have joined the Economy for the Common Good initiative. Some argue that the only way to prioritise circularity or sustainability genuinely is through not-for-profit businesses. In contrast, others contend that profit can still play a role, even as the primary objective, as long as the business is committed to resource reduction and profits result from genuine economic value creation.

Ownership structures facilitate: Not-for-profit enterprises naturally lack a profit imperative. Consequently, many scholars advocate for various ownership structures or incorporation models to mitigate the profit incentive. Not-for-profit businesses, including state-owned enterprises, foundations, consumer cooperatives, and not-for-profit corporations, can generate more sustainable value, depending on their purpose and strategy, as they are not constrained by market-driven logic.

However, the specific institutional arrangements, determined by their setup, can also lead to sustainable outcomes. This may encompass worker or producer cooperatives, social enterprises, or even private companies, depending on the precise governance structure and the owner(s) involved.

Responsible to all stakeholders: Another pivotal aspect in ensuring that businesses contribute to an overall reduction in resource consumption is the deliberate preservation, restoration, and enhancement of ecosystems. Equally important is transparency regarding the consequences of business activities, including those within supply chains, engagement with stakeholders, and throughout the product lifecycle. Only if this responsibility is genuinely embedded in the business will decisions become different.

In my view, the conclusion is that it is indeed possible to establish a sustainable business, and it can coexist with profitability. But it is hard to get there. This conclusion differs significantly from what is referred to as "sustainable business" in finance. According to this definition, most companies that score high on ESG or even impact and are part of sustainability indices cannot be categorised as truly sustainable. I would use a different label for such entities: less unsustainable companies. That might be a good topic for an upcoming newsletter: is green finance green finance, or green air around brown assets?

In the news

Degrowth as a next step in stakeholder governance: God piece by Harvard Law School (and not only because we figure in this). “Investors that include a degrowth lens in their analysis are focusing on companies that will benefit from a resource-constrained world. This includes companies that move to a model of less resource use, reusing materials, more efficient energy use, and more efficient manufacturing processes”

Autobesity: Newly-sold passenger vehicles (i.e., cars) are widening by one centimetre every 2 years in Europe. All signs suggest this trend will persist unless European law-makers take regulatory action. The current EU maximum width, set at 255 cm, was initially introduced in the mid-1990s to restrict the expansion of buses and trucks – it was never truly meant for cars. The limit falls short in curbing the proliferation of ever-wider SUVs (including pick-up trucks), and there's a strong argument for its review.

Lower emissions in Europe: The good news is that EU’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels drop 8% to reach lowest levels in 60 years. New analysis from CREA finds that the EU’s CO2 emissions have dropped to levels not seen since the 1960s. More than half of the 2023 reduction stems from a cleaner electricity mix. The bad news: it has to go faster to stay on track to be Paris-aligned.

That’s all for this week.

Take care.

Hans

The scale of the human enterprise isn't compared to population levels in this analysis. 8 billion Homo rapacious-superstitious create 800% the demand of 1 billion of a mere 200 years ago. Fine tuning technologies, and hoping for voluntary degrowth are not answers. Humans are not exempted from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maximum_power_principle

Nature will put us back into balance. The most humane way to do this are pre-pregnancy, pre-birth. Empowering women to control this is fought by patriarchal religions and societies. Indebted governments need more taxpayers, so resist shrinkage. Most businesses are addicted to growth.

Lastly, ~87% of humans live in Asia, Africa, and the Latin-Caribbean, most with values much different than the developed west/north. (N. America, Europe, AU/NZ)

Good luck treating the symptoms of overshoot while the drivers are in plague phase according to ecologists like Bill Rees (developer of Ecological Footprint analysis).

I am exploring secondary data to study the role ownership and governance play in making a firm an eco-sensitive organization. These views align with my initial hypotheses. Thank you for sharing.