#43 Armed Down to the Last Decimal

On economic rules, stylized facts, and the quest for control in uncertain systems

Hi all,

Holiday season. My holiday starts late tomorrow. But already last week to read, recover and rethink (and reread, rehearse (for swimming) - all the re-’s you can think of).

Many things have kept me busy. Currently (finally!), I have found some time to work on my book for a more extended period (partly based on my PhD), which gives me enormous pleasure. However, reading and writing also lead to many new questions.

I am still pondering the moral and philosophical implications of economics. Things like ‘value’, for instance. It is pretty challenging for an economist to remain detached from the utilitarian perspective on the world. But also, what is the difference between political economics and mainstream economics? You can not judge the current economic environment without understanding the power play. How have economists ignored power for such a long time? They now refer to it as geoeconomics (see, for instance, this paper). Still, it is nothing more (for most economists) than a reality check: the economy does not behave according to the model specifications. It is about people, human relationships, power and affection.

However, I leave that for another time. This time: about economic rules. Or the lack thereof.

Economics is often seen as the science of constraints. We celebrate it for its hard-nosed realism, its grounding in scarcity, and its promise to arbitrate difficult trade-offs. It presents itself as the guardian of discipline in a world of excess—a field that tempers politics with numbers and warns against utopian fantasies. But look closely, and this discipline that claims to be empirical often slides into something much less grounded: ritualised certainty, cloaked in decimals.

Few other domains lean so heavily on numbers that are, at best, stylised tendencies and, at worst, politically chosen anchors. Policymakers and institutions cling to these figures, not necessarily because they are correct, but because they offer the illusion of control. They give technocratic cover to fundamentally political decisions. Why 2% inflation? Why a 3% budget deficit? Why does debt sustainability begin to unravel at precisely 60% of GDP? These are not economic truths. They are conventions, elevated to the status of commandments.

Alongside these numeric targets are economic “laws” dressed up in historical regularities: Kuznets curves, which claim inequality or pollution rise and then fall with growth; Piketty’s r > g inequality dynamics; or the once iron-clad belief that raising minimum wages reduces employment. These began as stylised facts—observed tendencies in specific data at certain times. But through repetition, they became something more: assumptions hard-coded into models, and then into policy. Their original contingency was forgotten. Their context was flattened.

Yet many of these “laws” have crumbled under scrutiny. Kuznets' environmental optimism has not held in the age of climate change; r > g only tells part of the story, contingent on institutional settings and policy structures; the minimum wage-employment trade-off, once sacrosanct, has been revised by newer evidence. These aren't universal truths—they are patterns, observable only under specific configurations.

These numbers persist because credibility in economic discourse is tied not to truth but to consistency. Tweaking the decimal, even for good reason, can be branded irrational—or worse, politically untrustworthy.

Thomas Carlyle anticipated this dynamic in his 19th‑century critique of economics. He accused economists of reducing the moral and social world to machinery—of turning complex societies into predictable engines of inputs and outputs.1 This mechanicalism wasn’t just a method; it became a worldview. s Patrick Welch explores in Thomas Carlyle on the Use of Numbers in Economics, Carlyle was troubled not simply by economics’ dismal outlook, but by its fixation on reducing moral and civic complexity into quantifiable inputs and outputs. In this light, today’s decimal obsessions—2%, 3%, 60%—are extensions of that legacy. They are gears in a model of society that presumes knowable equilibria, fixed relationships, and rule-like behaviour.

Mechanical thinking sustains because it simplifies chaos. It offers a script: follow the rule, maintain credibility. However, every number was invented—for example, New Zealand’s early-1990s experiment with a 2% inflation midpoint, which the European Central Bank and others later adopted. No cosmic truth said inflation must be 2%; policymakers designed it rationally to anchor expectations. Yet now it feels like destiny.

But the world doesn’t operate like a steam engine. Economies evolve, institutions shift, people adapt, and feedback loops multiply. The comfort of mechanical rules becomes a liability in the face of systemic uncertainty.

So what should replace these false certainties?

This blog traces how specific numbers and “laws” became policy totems, how they survived long past their empirical expiration dates, and why they continue to guide governance despite their fragility. We will revisit the 'dismal science' label—not to discard economics, but to ask whether the discipline might be transformed. From a mechanical model of constraint into a narrative science of tendencies, values, and systemic interdependence. Apologies, it is kind of lengthy.

Short message for the time‑poor reader:

There are no universal laws in economics; instead, there are tendencies that emerge in specific institutional configurations. In market-dominated economies, growth dependence and policy predictability matter, but they do not mandate fixed decimals, such as 2% inflation. The endurance of these numbers is a matter of politics, not science.

The core takeaway of this blog is (this is also at the very end):

There are no universal economic laws. Only tendencies that appear in specific configurations (e.g., inequality under unregulated market systems).

Overreliance on fixed decimals—2%, 3%, 60%, r > g—imposes stability at the cost of adaptability.

Many of these rules outlived their evidence—the Kuznets Curve, EKC, Reinhart & Rogoff’s 90% debt cliff—and yet persist in policy.

Economics need not abandon its models, but it must reframe them within principles of justice, ecological sustainability, transparency, and resilience.

Narrative economics means telling systems stories: "Capitalism tends toward inequality—but democracy, framing institutions, and progressive taxes can bend the arc."

In that world, numbers are meaningful again—as tools that serve, not truths that bind.

We need an economics that is narrative-informed, principle-grounded, institutionally alert, and comfortable with uncertainty. One that treats targets as provisional aids, not metaphysical mandates. Because real economies are not steam engines. They are living systems shaped by ideas, power, and ecological limits. And that is the most powerful idea to end with: we live in our narrative, so we can recreate it in the way we want it to be.

It’s time to move from decimal dogma to deliberative direction.

And now it starts…

1. Where Numbers Come From

Many of the most cherished economic thresholds began not in nature, but in negotiation. I have only traced back the 2% inflation target and 60% and 90% public debt level thresholds.

Inflation targeting

The 2% inflation target—enshrined in central banks around the world—originated in New Zealand in the early 1990s, intended as a midpoint, not a divine revelation. It was designed to avoid deflation while anchoring expectations. But once adopted, it spread. The European Central Bank took it on. So did the Bank of England. The number gained an aura of inevitability.

To understand the basis of the 2% target, we look to the academic work that underpins it. Svensson (2010) explains that inflation targeting, including the 2% benchmark, was a response to the inflation volatility of the 1970s and 1980s, providing a clear anchor for expectations and enhancing policy credibility. The target aimed not to eliminate inflation but to strike a balance, ensuring price stability without veering into deflationary risks.

This pragmatic approach influenced the adoption of the 2% target; however, its widespread implementation has raised important questions about its effectiveness and broader economic implications. According to Mishkin, while the target has been successful in maintaining a stable inflation, it may have inadvertently neglected other critical dimensions of economic well-being, such as employment or wage growth.

Moreover, the potential limitations of the 2% target have been highlighted in the context of financial stability. Woodford argues that while inflation targeting helps maintain price stability, it does not necessarily prevent financial bubbles or safeguard broader economic stability, especially in the face of economic shocks.

The global adoption of this inflation target, including by the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, underscores its influence. The Bank for International Settlements examines how inflation targeting in Canada provided a model that was later emulated by other central banks, emphasising the importance of anchoring expectations in a way that avoids both runaway inflation and deflationary spirals.

In conclusion, while the 2% inflation target was not born from immutable natural law, its spread across central banks worldwide suggests its effectiveness in stabilising inflation expectations. Yet, as critics point out, its success in achieving price stability does not guarantee the same success in fostering broader economic health, suggesting that the target’s impact should be continually reassessed in light of evolving economic challenges.

Fiscal rules

Fiscal rules are no different. The Maastricht Treaty’s 3% deficit and 60% debt-to-GDP rules were less about scientific precision than political symmetry. These targets were designed to establish a framework for fiscal stability and prevent excessive deficits across the European Union (EU), with the underlying assumption that stable budgetary policy was essential for economic harmony. The idea was simple: if a country's economy grows at 5% nominal GDP (3% real growth and 2% inflation) and its deficit remains at 3%, debt levels would remain sustainable and converge to 60% of GDP. Simple, elegant, and easy to communicate. But in reality, macroeconomies don’t behave like spreadsheet simulations.

The 3% deficit rule, while designed to promote fiscal discipline, has been critiqued for its rigidity, particularly during economic downturns. Research by Alesina et al. (2015) underscores that the deficit limit, when enforced during recessions, often exacerbates economic instability. Austerity measures, which are usually implemented to meet this target, can deepen recessions, as they reduce government spending and investment in critical sectors. This, in turn, can lead to a cycle of low growth, lower tax revenues, and increased fiscal pressure. Alesina's work highlights the pro-cyclical nature of the 3% rule, which can force governments into a "race to the bottom" when trying to reduce deficits during periods of economic hardship.

Similarly, the 60% debt-to-GDP ratio, which has long been considered a safeguard against unsustainable debt accumulation, has its own set of criticisms. This threshold was initially intended to help maintain fiscal discipline and prevent the untenable accumulation of debt. However, it has been increasingly recognised as a somewhat arbitrary figure. The renowned economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff provided a foundation for debt sustainability arguments with their assertion that economic growth sharply slows when a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio exceeds 90%. Their findings in This Time Is Different (2009) lent weight to the notion that countries should avoid high levels of public debt at all costs. That finding quickly became ammunition for austerity policies worldwide. I remember that moment well—we handed every intern at the Rabobank economics team a copy of the book, believing it captured the urgency of the moment.

Until 2013, a young graduate student, Thomas Herndon, along with Michael Ash and Robert Pollin, attempted to replicate Reinhart and Rogoff’s findings and discovered spreadsheet errors, selective exclusions, and unusual weighting choices. Once corrected, the dramatic 90% “cliff” more or less disappeared in their analysis.

In other words, the whole 90% story, and the fiscal rules built around it, are resting on sand.

Yet the number persisted. Because policy needs anchors, and anchors don’t die easily.

But has the debt-growth relationship held up in broader empirical analysis? Not really. The most comprehensive answer so far comes from Philipp Heimberger’s 2022 meta-analysis, which includes 816 estimates from 47 studies. His conclusions are striking: after correcting for publication bias, the tendency of researchers and journals to highlight “negative” findings, there is no robust evidence that higher debt-to-GDP ratios systematically reduce growth. Moreover, there is no standard threshold, such as 90%, beyond which growth falls off significantly. Any such tipping points are susceptible to model choices, country samples, and econometric assumptions.

In other words, the whole 90% story, and the fiscal rules built around it, are resting on sand.

Heimberger also points out a troubling dynamic: estimates reporting more negative debt effects get more citations, regardless of their methodological strength. Papers published in higher-impact journals are less likely to reveal strong adverse effects. That says something about what we choose to see and celebrate in economics.

So, where does that leave us? Not necessarily in a world where debt doesn’t matter, but in one where context issues far more than the raw number. Countries with low interest rates and monetary sovereignty can sustain higher debt levels without triggering crises. And forcing governments to slash deficits in a downturn (to stay below an arbitrary 3%) can do more harm than good, deepening recessions and delaying recovery.

The European Commission seems to have taken note: recent reform proposals stress “net expenditure paths” and medium-term fiscal planning rather than rigid thresholds. But the ghost of the Maastricht rules still lingers in public debate, budget speeches, and the mind of every finance minister afraid to break them, even when doing so might be the economically rational choice.

Rules can help. But when the rule becomes the goal, economics turns into ritual. And we forget what public finance is actually for.

2. The Myth of Economic Laws

If numeric thresholds emerge from convention, economic “laws” often evolve from correlation. The most famous of these is Simon Kuznets’ hypothesis that inequality first rises, then falls, as economies develop. This “inverted U-curve” helped justify inequality in the name of growth. The second one to discuss is the r > g of Thomas Piketty.

Kuznets curves

Simon Kuznets was unusually candid for an economist. In his 1955 paper proposing the now-famous inverted-U relationship between income inequality and economic development, he ended with a disclaimer that feels almost quaint in today's world of data-driven certainties:

“In concluding this paper, I am acutely conscious of the meagerness of reliable information presented. The paper is perhaps 5 per cent empirical information and 95 per cent speculation, some of it possibly tained with wishful thinking”.

(Kuznets 1955, p 26.)

That admission, so modest, so transparent, should have been a warning. Despite that disclaimer, the inverted-U shape of the so-called Kuznets Curve took hold in economic discourse like gospel. For decades, it offered an elegant storyline: inequality is a temporary affliction on the path to prosperity, a passing discomfort we must tolerate while climbing the development ladder. Yet over time, as datasets expanded and methodologies improved, the curve’s simplicity gave way to deeper complexity and contradiction.

And indeed, as decades of research have shown, there is little empirical foundation to support the sweeping conclusions that later economists, policymakers, and pundits drew from his initial hypothesis. While the Kuznets Curve offered a tidy story—inequality first rises and then falls with economic growth—subsequent studies have painted a far more complex and inconsistent picture.

Larger-scale research using the Deininger & Squire dataset (covering 96 countries) found only limited support for a universal curve. In many cases, the pattern disappeared when region-specific factors were taken into account, notably dummy variables for Latin America and Africa. A global panel study by John Thornton confirmed an inverted‑U only under restrictive assumptions; once broader heterogeneity is controlled, the pattern weakens dramatically. Other comprehensive reviews argue that modern economic theory does not predict a single outcome; growth and inequality interact in various ways, depending on political institutions, social structures, and historical contingencies.

Indeed, studies tracking inequality over extended periods in advanced economies, such as the U.S., U.K., Germany, and France, find N-shaped trajectories—inequality rises, falls, then rises again—rather than a clean inverted U. Economic historians caution that mid-century declines in inequality were profoundly shaped by war, depression, and policy reforms—not inherent to rising income alone.

The Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) is rooted in a provocative analogy: just as Simon Kuznets hypothesised in 1955 that inequality first rises and then falls with economic development, environmental degradation, too, might follow an inverted-U trajectory. This idea, while speculative in its economic origins, found traction in environmental economics in the early 1990s when researchers such as Grossman and Krueger (1991) first empirically suggested that pollutants like sulfur dioxide peaked and then declined as incomes rose. Panayotou later coined the term "Environmental Kuznets Curve" to describe this pattern.

The EKC gained policy appeal. It suggested that pollution, much like inequality, could be a temporary side effect of growth—a phase that wealthy nations would naturally outgrow. By the time the World Bank's 1992 World Development Report popularised the idea, it had become an optimistic counterpoint to the environmental pessimism of The Limits to Growth (1972).

However, this optimism has not aged well. As a recent systematic review reveals, the EKC is far from universally observed, and its empirical foundation remains tenuous. Their meta-study, covering over 100 EKC-focused papers from 1991 to 2023, concludes that EKC findings are highly inconsistent, dependent on the pollutant studied, the model specification, the period, and the geographic scope. While some local pollutants (e.g., SO₂) exhibit an inverted-U pattern in high-income countries, global pollutants such as CO₂ do not reliably follow the curve.

Moreover, the EKC is often misunderstood as a law rather than what it is: a statistical artefact sensitive to variable selection and model structure. Many studies that appear to support the EKC use GDP squared as a regressor, often with questionable assumptions regarding causality. When more complex dynamics and control variables—such as energy mix, urbanisation, and trade openness—are introduced, the curve often flattens or transforms into (again!) N-shaped or monotonic relationships.

Their findings also underscore that sectoral-level studies (as opposed to national-level studies) sometimes validate EKC dynamics more reliably, suggesting that any such curve is contingent and fragmented, rather than general or automatic. Critically, they emphasise that early optimism around the EKC underestimated the time it might take for countries to reach the so-called "turning point"—and whether environmental systems can withstand the damage incurred before that point is ever reached.

Thus, the EKC has shifted from a hopeful hypothesis to a contested terrain. Rather than assume pollution will decline with growth, Guo and Shahbaz urge more caution, more critical modelling, and a rethinking of environmental policy assumptions that rest on passive economic trajectories.

Taken together, the failure of both the Kuznets Curve (inequality version) and the trickle‑down hypothesis underscores a clear lesson: equity is not an emergent property of growth. Rather, equality depends on intentional policy—progressive taxation, redistributive transfers, public investment in healthcare and education, labour rights, and environmental protections.

If there’s one thing to salvage from Kuznets’ caution—that his theory was largely speculative—it’s that we’d be wise to heed it. Growth, left to its own devices, does not guarantee justice—nor does concentration of wealth trickle down to everyone else. Those outcomes must be purposefully designed.

Piketty’s r>G

Thomas Piketty’s simple yet powerful insight (r > g, the notion that the return on capital typically exceeds economic growth) has been hailed as a modern law of capitalist inequality. In Capital in the Twenty‑First Century, he marshals historical data showing that long-run averages for the rate of return on capital (including profits, dividends, interest, and rents) sit around 4–5 percent per year, while GDP growth seldom exceeds 1.5–2 percent. From this emerges a worrisome dynamic: capital accumulates faster than overall output, and crucially, in an economy where capital ownership is highly concentrated, this process deepens inequality.

Piketty’s assertion echoes, of course, Marx’s critique of capitalism, where capital accumulation is an engine of class stratification. While Marx focused on surplus value, Piketty’s r > g repackages the idea for the age of compound returns, arguing that wealth inherited or invested compounds faster than economies can grow. In doing so, Piketty revives a classical-materialist framework in contemporary terms.

Yet, this apparent law is deeply contingent on the frameworks within which economies operate. As Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson argue in The Rise and Decline of General Laws of Capitalism, overarching generalisations like r > g risk overlooking the institutional architecture and social norms that radically mediate outcomes. Drawing on contrasting histories, such as those of Sweden and South Africa, they contend that the dynamics of inequality cannot be understood apart from political regimes, tax systems, property rights, and power relations. In other words, no economic law holds in all contexts—unless it embeds the force of institutions.

Into this institutional critique comes Emiliano Brancaccio and Fabiana De Cristofaro’s rejoinder. They acknowledge Acemoglu’s caution but maintain that certain tendencies, such as wealth concentration and systemic instability, are "gravitational pulls" in capitalist economies. These are not iron-clad predictions but persistent tendencies: the laws don’t force outcomes, but they nudge systems unless institutions intervene. Therefore, while r > g is not fate, it becomes structurally robust in the absence of progressive taxation, inheritance limits, or redistributive policy.

Robert Boyer’s regulation theory offers a helpful middle path. He portrays capitalism as evolving through successive regimes—Fordism, neoliberalism, financialization—each anchored in a specific regime of accumulation and a corresponding mode of regulation. These regimes shape how capital is deployed and returns are realised, and they shift when crises expose contradictions. The tendency of capital to accumulate and the potential for r > g dynamics emerge most clearly in regimes where redistributive feedback loops are weak, a pattern not immutable, but historically contingent.

So, where does that leave us? Piketty’s r > g remains one of the most compelling explanations for long-run inequality. But it is not a universal law. It is a structural tendency, deeply conditioned by institutions, norms, and policy frameworks. As Acemoglu reminds us, historical paths differ because institutions differ. As Brancaccio emphasises, tendencies persist unless countered. And Boyer situates these patterns within cyclical regimes, constrained and reshaped over time.

Ultimately, the truth of r > g isn’t sealed in mathematics. It’s a political-economic question. If societies are to avoid runaway capital growth at the expense of broad shared prosperity, they must consciously design institutional guardrails: progressive taxation, inheritance limits, public investment, and effective regulation. Absent those, the simple arithmetic of growth and returns becomes a self‑fulfilling logic of inequality.

Narratives and Principles: Rethinking Economics Beyond the Decimal Dogma

In place of rigid, decimal-driven policy, we must champion an economics rooted in narratives and guiding principles. This shift is not about abandoning rigour; it’s about reordering our belief that numbers are truths and instead viewing them as instruments embedded in values and institutional context.

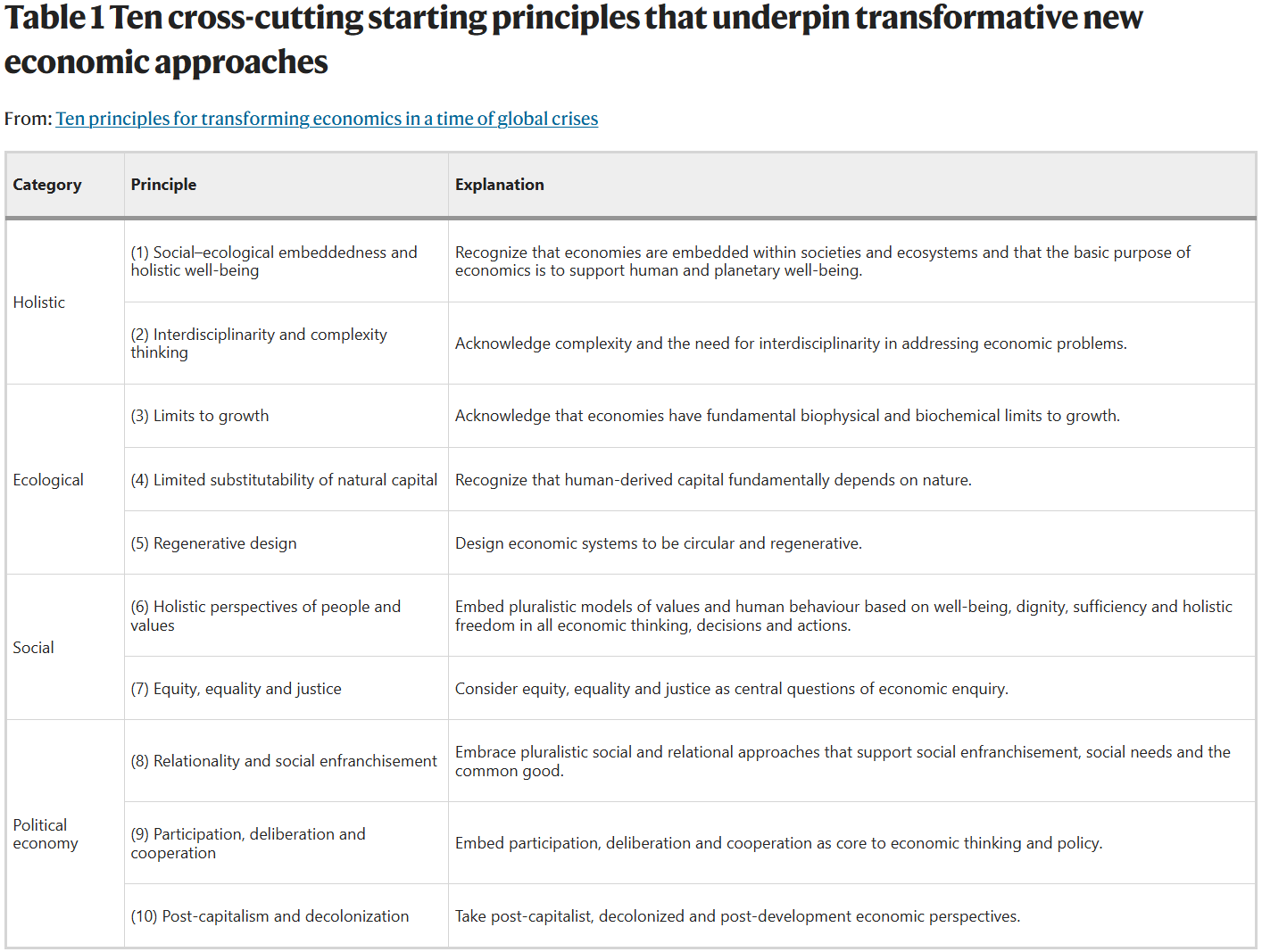

A recent paper in Nature Sustainability by Brand et al. (2025) makes a clear case that sustainability success depends less on mechanical rules than on principles embedded in governance (see below the ten principles). They identify moral and institutional principles, principles of fairness, transparency, precaution, and resilience, that should guide economic policy, especially in ecological and social domains. Their analysis and conclusions are close to those that I found in my PhD thesis. Just as scientific models rely on underlying philosophical assumptions, so too must economic models be paired with normative principles. Otherwise, they risk ossifying into a ritual devoid of meaning.

Building on this, we can reimagine policy not as calibrations to fixed targets, but as expressions of core principles. Imagine inflation policy aligned not just with a 2% figure, but with the principle of expectational credibility and distributive neutrality: it’s not the number itself, but its stability, public trust, and policy transparency that matter. Similarly, rather than defaulting to a strict 3% deficit cap, consider the principle of countercyclical solidarity and fiscal resilience: deficits are permissible during crises when they support social welfare and recovery, provided transparency and democratic accountability are robust.

Narratives provide the lens: “Growth is necessary, but it must align with ecological limits.” Principles provide the guardrails: “Redistribution should address inequality, not undermine productivity.” This aligns with the view that economics should be a storycraft discipline, one that blends material tendencies—like capital accumulation—with ethical clarity, political agency, and ecological awareness.

As Brancaccio and De Cristofaro remind us, macro tendencies—inequality, accumulation, and volatility are not inevitable laws. They are patterns that emerge unless societies intentionally counteract them. So the narrative becomes: “We recognise the tendency of r > g to exacerbate inequality—but we choose principles and institutions that subvert it: inheritance tax regimes, public investment, regulation.” That is far richer than declaring “r > g law always holds.”

Adolfo Figueroa’s Unified Theory of Capitalism presents a structural narrative, comprising eight empirical regularities that describe the relationships among capital, inequality, growth, and the environment. Yet Figueroa himself insists these regularities are contextual tendencies, not iron laws. They coexist alongside institutional design and are shaped by political power. His warning aligns with Brand et al.: models must be anchored in principles, not converted into dogma.

Ultimately, narratives and principles ground economics not in decimal ritual but in purposeful coordination. They help us ask: What kind of society and economy do we want to have? Under what moral and ecological constraints? Then we derive numeric targets—whether inflation, debt levels, or wages—not as commandments but as consistent tools, defensible to public scrutiny, revisable in crisis, and transparent in both process and implication.

From Decimal Dogma to Deliberative Direction

If economics has too often disguised convention as clarity, the alternative is not to discard models or dismiss numbers. Instead, it is to re-secure them in narrative and ethics.

The core takeaway of this blog is:

There are no universal economic laws. only tendencies that appear in specific configurations (e.g., inequality under unregulated market systems).

Overreliance on fixed decimals—2%, 3%, 60%, r > g—imposes stability at the cost of adaptability.

Many of these rules outlived their evidence—the Kuznets Curve, EKC, Reinhart & Rogoff’s 90% debt cliff—and yet persist in policy.

Economics need not abandon its models, but it must reframe them within principles of justice, ecological sustainability, transparency, and resilience.

Narrative economics means telling systems stories: "Capitalism tends toward inequality—but democracy, framing institutions, and progressive taxes can bend the arc."

In that world, numbers are meaningful again—as tools that serve, not truths that bind.

We need an economics that is narrative-informed, principle-grounded, institutionally alert, and comfortable with uncertainty. One that treats targets as provisional aids, not metaphysical mandates. Because real economies are not steam engines. They are living systems shaped by ideas, power, and ecological limits. And maybe that is the most powerful idea to end with: we live in our own narrative, so we can recreate it in the way we want it to be.

It’s time to move from decimal dogma to deliberative direction.

Stay safe.

Hans

And yes, the phrase dismal science first emerged in Carlyle's article "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" (1849), in which he argued slavery should be restored to reestablish productivity to the West Indies. In the work, Carlyle says, "Not a 'gay science,' I should say, like some we have heard of; no, a dreary, desolate and, indeed, quite abject and distressing one; what we might call, by way of eminence, the dismal science."