Hi all,

I have travelled extensively over the last few weeks and encountered many inspiring discussions, ideas, and confusions. Two main questions came up: First, how radical is the change we need in society to create an economy that delivers well-being for all now and in the future, and second, why is there still a massive mismatch between societal needs and capital that is allocated to them?

Sometimes, we dove deep into some conceptual ideas. We had a session about “questioning the system” at the sustainability forum Springtij at Terschelling. It turned out to be about questioning what the system is. While this might sound trivial, it is very relevant to have a more in-depth discussion about this occasionally. Of course, you might claim that ‘we’ are the system: every relationship we have, every connection and every action of every human being, living species or living organism determines how a system evolves. However, some properties of a system will only pop up in certain interactions: you can say that we are always a traffic jam, but it only occurs when many of us drive a car during rush hour. We are not in a traffic jam; we are in a traffic jam. And because we are a traffic jam (as an emergent property of the system that can occur under certain circumstances), we are all responsible for those features and can only avoid this property by collective action (of course, you can avoid a traffic jam by going by public transport - but this is not solving the collective problem).

Furthermore, the group unequivocally agreed that a system includes everything relevant to our existence. The economy is a subsystem of that total system, and the financial sector is (again) a subsystem. So, suppose you want to say something about sustainability challenges. In that case, you will always have to discuss the link between economic, social and ecological systems because the economy is embedded in nature and social relationships.

Let’s return to the two huge questions posed in the beginning: How radical is the change we need, and what is wrong with finance? Don’t expect answers, only considerations…

How radical is the change we need?

For the first question, I think the answer lies in first defining the purpose of our system. We must be clear about our collective goals and shape markets and policies to achieve those goals. Much inspiration for this can be found in, for instance, the work of Mariana Mazzucato. In this recent article, she strikes a balance (at least in my opinion) between criticising the market and how to define a common good. In her opinion, the common good can be achieved by setting a collective objective rather than a correction, focusing as much on the “how” as the “what”. In other words, correcting market failures or improving government actions is not defining a common good. Also, she posits that it is not about the growth rate but, maybe more importantly, its direction. Explicitly defining a direction towards which policies may be designed, public-private partnerships formed, and citizens engaged is critical to shaping the economy to serve the common good.

Five pillars can help define a common good (see figure).

I don’t know if it will fully accomplish the task, but it helps define the gap between the (collective) objective and the current state.

After defining the system's purpose, the second step is determining how to achieve it. This can be done through markets (and correcting market failures), government actions, or society. Of course, this highly depends on worldviews and the system's definition (again!). Suppose you take the economic system as your focus of analysis and see social and ecological effects as by-products. In that case, the objective becomes efficient transactions, which can best be achieved if all externalities are priced. However, if you start with ecological or human values, pricing can only be helpful but still insufficient. You might need limits, bans, norms, et cetera.

Most people usually begin with the third step, discussing policies and transitions. Of course, this is important. Only analysis doesn’t lead to any change. But (and that came also up in quite some discussions), it might be useful to take a step back first. Look at what makes sense and what does not. Where are the leverage points in the system? Where do we waste our time? What helps to transition, and what will only lead to new lock-ins? For example, I am afraid our focus on automotive electrification is not a sufficient bridge strategy. As this article states, we might have the problem of ‘scope incumbency’ through which prevailing power arrangements shape ideas about the future.

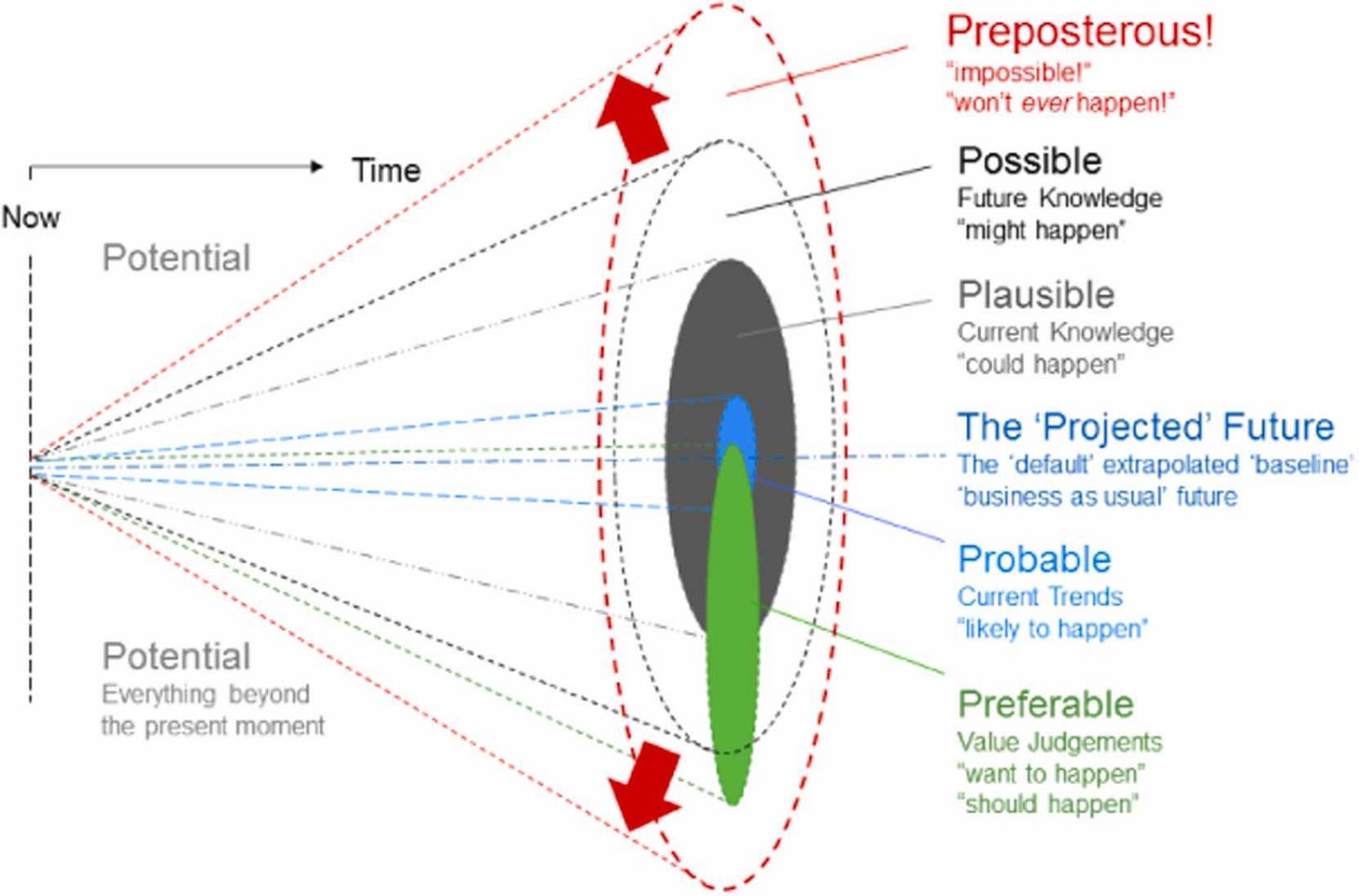

We simply don’t use all possibilities, but foremost, we extrapolate (another case on this for Dutch readers, the new scenarios of the CPB).

After these three steps, we might be able to come up with a proper answer. And, given the latest outcry from scientists (see here), radical action is needed in Perilous times on planet Earth. A quote:

In a world with finite resources, unlimited growth is a perilous illusion. We need bold, transformative change: drastically reducing overconsumption and waste, especially by the affluent, stabilizing and gradually reducing the human population through empowering education and rights for girls and women, reforming food production systems to support more plant-based eating, and adopting an ecological and post-growth economics framework that ensures social justice. Climate change instruction should be integrated into secondary and higher education core curriculums worldwide to raise awareness, improve climate literacy, and empower learners to take action. We also need more immediate efforts to protect, restore, or rewild ecosystems.

Source: Ripple et al. (2024)

So, my answer (of course): We need more radical action than most of us want and more than what is politically feasible; that is why we are so into nitty-gritty non-solutions, making the economy even more complex without having real solutions. Is this a satisfying answer? No. But I said I would only give some consideration here.

What is wrong with finance?

It is clear that finance is doing a lot and is dominant in (many) decisions, but it is not delivering on societal needs.

But where to start?

Maybe with the beautiful artwork of Carlijn Kingma, the Waterworks of Money (see also below). She clearly shows what is wrong with finance. The water stays at the top and is not trickling down.

But maybe more detailed. I now come to five huge failures—and I probably miss some. Because of the current financial system's setup, there is absolutely no incentive, let alone a guarantee, that capital will or can be directed at societal needs.

I will discuss them individually without going too deep (because this is still a blog post, not a dissertation).

#1 A highly leveraged system

Let’s start very simple. There is nothing wrong with leverage. There is nothing wrong with debt. But if it is too high, it might be a problem. I am not discussing the leverage of ‘only’ the banking sector. For that, it can be argued that leverage has gone down given tighter regulations. No, if we simply take the global economy, it is clear that we have a structural upward trend of more debt in terms of GDP. And even more so if we would compare it to our ecological basis. It is a combination of public debt and private debt, the debt of rich and poor countries.

Why is this a problem? Well, it is clear that debt needs to be repaid at some point. And that means extra real economic activity for an economy already in overshoot.

#2 A system that is increasingly disconnected from the real economy

A different way to look at the financial system is to take the global balance sheet: the net worth (of the largest economies) and then divide it by GDP (see figure)

McKinsey did that exercise. Their conclusion:

Around the year 2000, with timing that varied by country, net worth, asset values, and debt began growing significantly faster than GDP. In contrast, productivity growth among G-7 countries has been sluggish, falling from 1.8 percent per year between 1980 and 2000 to 0.8 percent from 2000 to 2018.

In other words, financial wealth became increasingly detached from the real economy (as we take GDP as a proxy for real, which you can also have your opinions on).

Why is that a problem? It means that more and more capital is ultimately not linked to (real) economic activity.

#3 An extractive system

Another way to look at it is to see what part of the real economy is financialised. I use here a graph I made for our investment outlook a few years ago, but the original is from Nate Hagens.

In simple terms, we first used fossil energy to drive the economy. After the oil crisis in the 1970s, we solved the growth problem by 1) using debt to pull consumption forward in time and 2) globalization and outsourcing to the cheapest areas of production. These changes allowed economic growth to continue until it hit a wall with conventional finance in 2008 when central banks and global governments were forced to redesign the entire financial system. This new (ongoing) paradigm involved measures such as too-big-to-fail guarantees, artificially low interest rates (even negative!), quantitative easing, central bank balance sheet expansion and various GDP-friendly rule changes. We are heading towards the point where our global monetary representations of reality continue to decouple from the underlying biophysical reality (see also McKinsey above). As extra sources, finance is now searching for new asset classes, such as nature-based solutions.

I guess I don’t have to explain why this is a problem.

#4 A concentrated and non-diverse system

I have made this point many times before. We have concentration problems and a lack of diversity in all parts of the financial system. This holds for asset managers (who have gained tremendous power in the last decades; see Benjamin Braun’s asset manager capitalism research). Still, the same concentration trends happen in banking, credit cards, rating agencies, consultants, et cetera.

Lack of diversity and too much concentration are also problems in banking. Why? Because we then have (still) the problem of too big to fail. Banks that can not go bankrupt because they then will threaten (national or international) financial systems, including payment systems (is that not a public utility?), household savings, SME loans, et cetera.

#5 A system where normative decisions are made, although participants pretend it is all objective.

A repetition from another post. But it's still essential.

A classic mantra is the triangle of impact-risk-return, also called the investment trilemma. While, as everyone knows, the relationship between risk and return is fixed in terms of how to calculate, what assumption you can make and what evidence you have, it is not related to impact. And although we have many rules to assess return and risk (appetite), it is not to say it is ‘objective’ in any way. It depends (forward-looking) on our assumptions of expected profit growth, risks and discount rates we use. Discounting the future is always a normative exercise.

And where there is (at least ex-ante) a well-known trade-off between risk and return, it is less clear, especially in the longer run, how this relates to impact-risk-return.

Of course, this is not all. Money creation, interest rates, and morality also play a role, to name a few. But as I already told you, these are only considerations…

There is so much more to say and write about this topic. But not for now.

Thanks for reading.

Take care,

Hans

We need a shift towards a well-being economy. Degrowth not only would address a lot of the climate change symptoms, but even the issue itself. And when it comes to human welfare, well, it's even more visible.

Ik ben ervan overtuigd dat we de denkoefening moeten maken over waar we naartoe willen, doelen, normen, waarden en dan een systeem conceptualiseren om daaraan te voldoen.

Het bovenstaande is sowieso geen globale denkoefening want het speelt zich enkel af in de hoofden van de deelnemers.

Waar ik meer heil in zie is onze A. huidige uitdagingen in kaart brengen (is al veel gedaan) en dan de B. overkoepelende en fundamentele oorzaken filteren (is minder gedaan). Deze tegen het licht plaatsen en C. bedenken wat er aan het systeem moet veranderen om deze uitdagingen te tackelen. (zie onder)

Welke normen en waarden kunnen we hiervoor gebruiken met een globaal karakter? Ik zou de universele rechten van de mens nemen en deze dan uitbreiden met een ecologische context. De ecologie als rechtspersoon een evenwaardige zitje aan de onderhandelingstafel geven.

Om de oorzaak van het meest urgente probleem binnen onze poly-crisis te identificeren, moeten we bepalen welke fundamentele driver meerdere crises tegelijkertijd verergert. Een dergelijke overkoepelende oorzaak is de niet-duurzame exploitatie van natuurlijke hulpbronnen, aangestuurd door een 1. combinatie van economische groeimodellen, 2. consumentengedrag en 3. industriële praktijken.

In deze post zal ik mij houden aan B.1:

Het is een geldig en inzichtelijk perspectief om te stellen dat de grondoorzaak van ons economische groeiparadigma ons financiële systeem is. Het financiële systeem, met zijn nadruk op krediet, schuld, winstmaximalisatie en aandeelhouderswaarde, drijft inderdaad de meedogenloze jacht op economische groei aan. De overgang naar een model dat duurzame maatgetallen/metrics voor mensen, planeet en welvaart omvat, kan veel van de meest urgente mondiale problemen aanzienlijk aanpakken.

Grondoorzaak: het financiële systeem

Krediet en schuld:

Het financiële systeem is sterk afhankelijk van krediet en schuld, wat voortdurende economische groei vereist om deze verplichtingen terug te betalen en te onderhouden. Dit creëert een cyclus waarin economische expansie essentieel wordt voor het behoud van financiële stabiliteit.

Winstmaximalisatie:

Bedrijven en financiële instellingen geven prioriteit aan winstmaximalisatie, vaak ten koste van milieu- en sociale overwegingen. Deze korte termijn focus op financiële opbrengsten leidt tot exploitatie van hulpbronnen en aantasting van het milieu.

Shareholder Value:

Beursgenoteerde bedrijven staan onder constante druk om aandeelhouderswaarde te leveren, wat betekent dat ze hun inkomsten en winsten moeten verhogen. Deze druk houdt een op groei gericht economisch model in stand.

Door het financiële systeem te erkennen als een grondoorzaak van het economische groeiparadigma en over te stappen op een model dat duurzame maatgetallen/metrics voor mensen, planeet en welvaart omvat, kunnen we de meest urgente mondiale problemen aanpakken. Deze verschuiving vereist uitgebreide veranderingen in beleid, bedrijfsgedrag, financiële praktijken en maatschappelijke waarden, maar het is een cruciale stap naar een duurzamere en eerlijkere toekomst.