#26 In search of our natural state

It is more about radical change that being for or against economic growth

Hi all,

The summer is almost over, many people are back to work, and the discussion on progress and sustainability is heating up once again. We have the debate about green growth and degrowth in a new episode, new research on decoupling carbon emissions from economic growth and the latest research on alternatives for GDP. Not all of this is controversial, but at least for me, it leads to the same conclusion: We need a discussion about the underlying paradigm (not about the symptoms) and more radical change. We need to define our natural state.

Let me explain. First is the debate about green growth versus degrowth. I must admit that I often also contribute to this debate over whether economic growth can continue in light of our sustainability challenges—from biodiversity loss to resource scarcity.

This week was marked by another stage in this discussion: an article in Ecological Economics claiming that most Degrowth studies report opinions rather than analysis, that there is ample empirical proof, that there is a lack of methodologically sound research on the topic and that most studies offer ad hoc and subjective policy advice, lacking thorough policy evaluation and integration with critical insights of the broad literature on environmental/climate policies.

Oof, you think. Say goodbye to degrowth. And that is what happened: some people heralded this as being ‘finally’ shown that degrowth is a bad idea, that all research that talks about limits and demand policies is bullshit and that this discussion is over.

They seem to forget (or don’t know) that the same journal, with the same peer review process, has many papers that come to different conclusions, also in overview articles (like this one).

What is my opinion on this? Criticism of methodology and assumptions should be part of the regular academic debate. However, I think this one gets derailed by egos and interests. And that distracts from a genuine discussion.

But, more importantly, the discussion on degrowth, green growth, or whatever is not that interesting. We can have a fitty between people with the same objective (a more sustainable economy), and they don’t agree on the instruments or the order of their use. But the honest discussion is in what you think is the natural state: is an economy always possible to grow?

Also, a Nature article reported on the relationship between economic growth and carbon emissions this week. Their results were clear: although in some (wealthy) countries, we see absolute decoupling (decrease of carbon emissions while GDP rises) happening, but not in most of the world’s nations. So, their conclusions:

For most countries, the evidence shows that economic growth is still associated with more carbon emissions, which indicates that the decoupling of economic growth and CO2 has not yet been achieved on a global scale. Even assuming that the general observed trend of decreasing elasticities over time could eventually lead to turning points in the future in which emissions would start decreasing with economic growth, there would still be positive emissions for most countries. This makes current climate targets, like the Paris Agreement’s target of limiting temperature increase to 1.5ºC or 2ºC above pre-industrial levels, difficult to achieve.

Focusing on the results obtained in this study, it has worrying implications for both regions and individual countries regarding the climate policies carried out over the last decades, considering the urgency required to mitigate climate change. Only in wealthy regions have a majority of countries already decoupled GDP per capita from CO2 emissions. However, this represents a small part of the world, and economic growth in most regions will still be associated with higher emissions, leading to greater emissions at the global level. So, the first and most important general implication of these results is that countries must effectively implement, accelerate or rethink this kind of policies, as they may not be working as fast as needed. Given the global nature of the effect of carbon emissions, individual countries have lower incentives than regions or the whole world —many countries have decoupling shapes—. This is why is so important a coordinated and effective action.

Source: Freire-Gonzalez et al. (2024)

So, another oof in one week: no evidence exists that carbon emissions can be decoupled from economic growth. And whatever the research tells about the feasibility of degrowth proposals, we have a problem.

Again, concentrating only on degrowth versus green growth does not work. I suppose both green growth advocates and degrowth proponents agree that the long-term functioning of the economy should ensure our planet remains somewhat livable. In that case, it doesn’t matter whether this happens with or without growth. After all, very few in this debate argue that economic growth is an end in itself. I think there is another, more difficult discussion behind it—growth belief. The belief is that economic growth is the natural state. But is it?

Growth belief

Most of us have grown up believing growth is the standard, natural state. We have witnessed it in our lifetimes and also observed that stagnation or declining activity results in problems: unemployment, bankruptcies, austerity policies, etc.

Interestingly, in this regard, is that after the widely quoted definition of sustainable development in the Brundtland report1 , the paragraph after that reads as follows: "The concept of sustainable development does imply limits - not absolute limits but limitations imposed by the present state of technology and social organisation on environmental resources and by the ability of the biosphere to absorb the effects of human activities. But technology and social organisation can be both managed and improved to make way for a new era of economic growth." (WCED, 1987, p. 16). It is clear from this statement that the hegemony of economic growth as the primary economic objective was not changed with the UN agenda on sustainable development and neither by all indicators that followed.

That is the underlying growth dependency of our economy. People don’t seem to notice. But this dependency, inherently and by humans, is the problem—and maybe a solution. If we understand that it is a belief, a worldview that can (and maybe) must be changed, much more can be feasible. In essence, growth dependency encompasses "Those conditions that require the continuation of growth in order to avoid significant physical, psychological, social, and/or economic harms." (Corlet Walker et al., 2024).

Growth dependence can be seen as an emergent property of a system: non-existent at a micro level but appearing at the macro level. This is also why growth dependence is irrelevant from a microeconomic, individual perspective: the (economic) question of utility maximisation under scarcity will never lead to the conclusion that growth is necessary at a personal level.

So, let’s discuss growth belief. We’ve created a volatile, growth-addicted society. There are numerous reasons why our current society needs growth to avoid collapse.

The first is the market economy. Markets operate efficiently when there’s competition; companies profit most when they outperform and innovate more than their competitors. The greater the profits they seek, the stronger the drive for efficiency and the desire for a growing economy. After all, growth means more revenue, with a bigger pie for everyone.

As companies produce more efficiently, fewer workers are needed. Workers are also interested in a growing economy, which creates new jobs. This growth pressure intensifies when companies pocket a large share of the profits. Capital accumulation is a growth drain.

The design of the financial system also contributes to growth addiction. Banks create money by issuing loans. The bank doesn’t care much about what happens with the loan as long as the money and interest are paid back. But this debt must ultimately be backed by economic activity. Debt is a claim on future growth.

Finally, the government also relies on growth. After all, growth benefits budget balance. Growth leads to rising tax revenues because tax bases (income, profit, revenue) increase with growth. With upward pressure on government expenses (from ageing, health care, and politics), growth helps ease many discussions. Distributional conflicts can be avoided through growth.

There is much more to say about this (and many more academic references), but I think these are the main points about our growth imperative.

So, given how our system is structured, the desire for growth is perfectly understandable. But these are our own rules. Growth pressure creates a belief in growth. As long as there’s growth, that’s not a problem.

And that is precisely the issue in many wealthy countries. We’re ageing and don’t want to admit more people, so the workforce isn’t growing or is even shrinking. Labour productivity hasn’t increased significantly for decades, either. It seems to be the case that economic growth for the coming decades will not be enough to satisfy our growth needs.

So what do we do? Do we allow ourselves to have the real conversation about how to make our system design more sustainable, inclusive, and future-proof so that a system can endure even without growth? Or do we insist that perpetual economic growth is a natural phenomenon and believe it can be green? Growth or progress belief is the debate we need to have.

Alternatives

I think (that should be clear by now) that this deserves a thorough discussion: an agenda to reduce growth imperatives, a policy agenda not solely directed at more growth. This is a (subtle) difference with a degrowth agenda that proposes an alternative. It is a transition agenda: from the current place that the world economy is in towards a different place we do not yet know, that we must discover. Therefore, I agree that some degrowth proposals are unimplementable in our current economy. But this also has much to do with our ‘growth mindset’: the underlying worldview that markets deliver prosperity and that individualism is good and always better.

A part of the search for alternatives is determining which indicators can help us steer that transition. A new article tries to bring all the beyond-growth literature (concentrating on metrics) together (see below) and proposes an integrated approach.

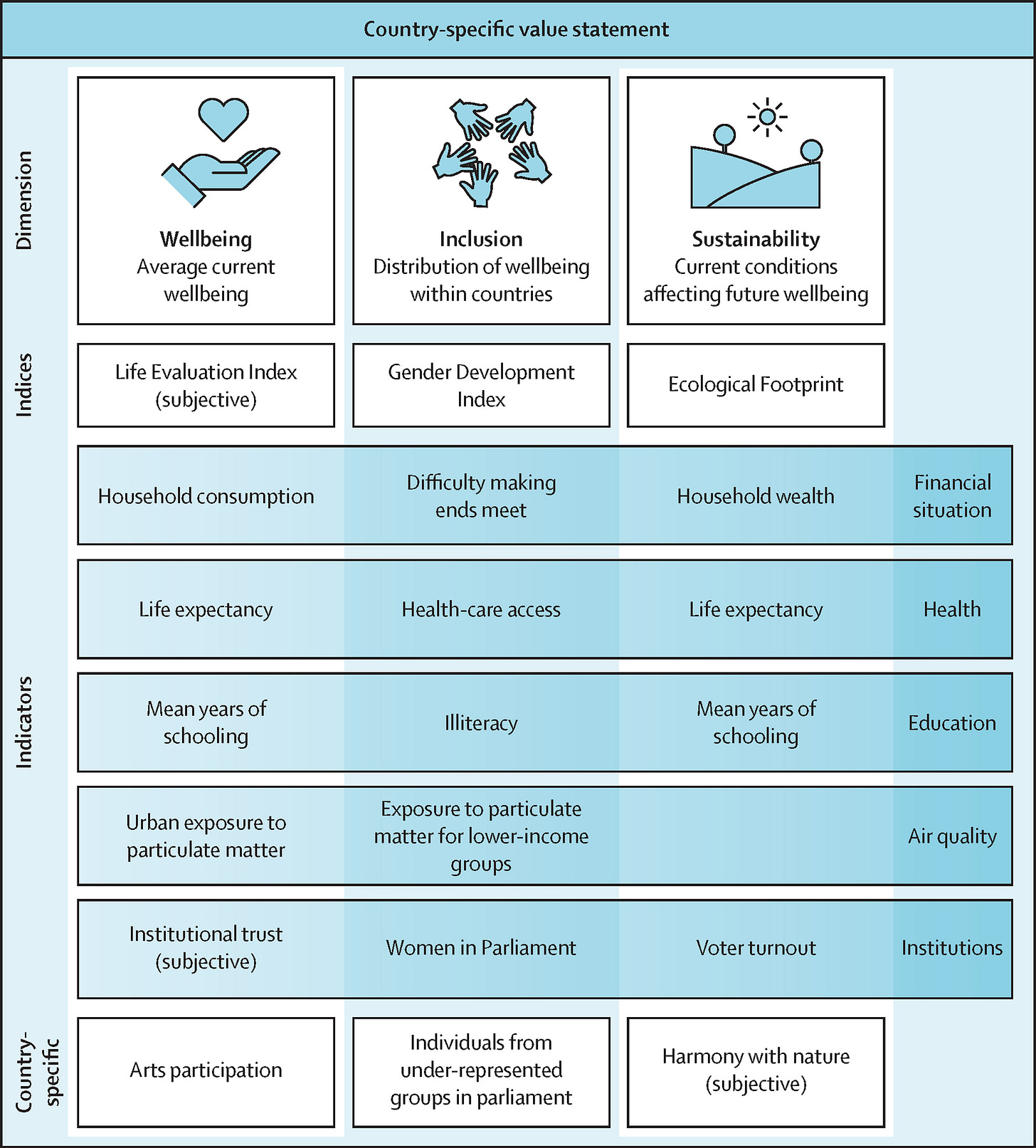

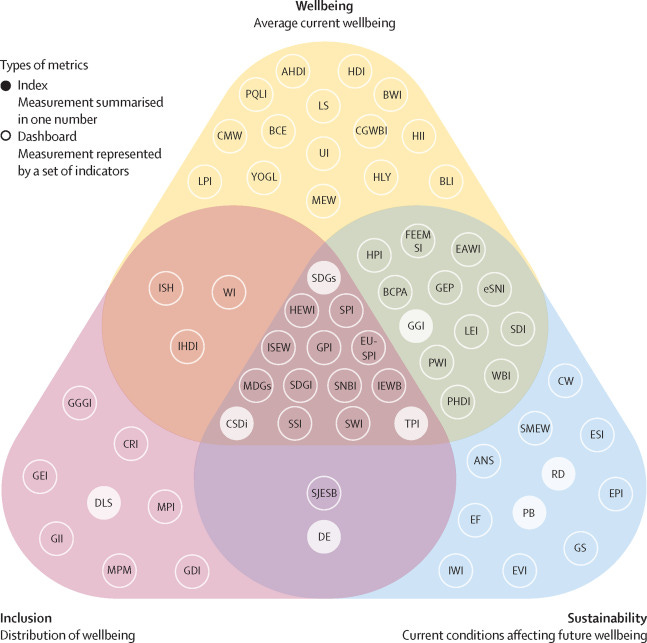

The triangle shows an overview of 65 Beyond GDP metrics plotted based on well-being, inclusion, sustainability, or a combination of two or three dimensions.

They come up with a proposal to align all those different indicators:

Based on the review of existing metrics, we created a structured dashboard to embed the headline indicators to be considered at the UN's 2024 Summit of the Future (figure 4). This framework addresses the core challenges for a successful Beyond GDP transition. First, it enables an interdisciplinary approach by embedding three dimensions (wellbeing, inclusion, and sustainability), as well as objective and subjective indicators to measure development within these dimensions. Second, the framework allows for the inclusion of existing metrics, again structured according to the three dimensions to elucidate the measurement objective of specific metrics. Last, the dashboard balances the requirements for a standardised and interdisciplinary measurement framework with flexibility to account for country-specific circumstances.

I think it is a practical and highly needed attempt to integrate all the good thinking, align it and help to get (in a statistical way) beyond GDP.

However, such a new approach would only help if it is (1) embedded in policy agendas, (2) gets a central place in the world’s governance and statistics, and (3) if we can assess the growth imperatives in our economies.

If we fail to do the latter, these new statistics will never surpass GDP but will only serve some goals beneath GDP.

This week's conclusion is that a more sustainable economy can only be achieved through more radical, integrated thinking.

That’s all for this week.

Be nice

Hans

“humanity has the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987, p. 16).