#23 Holiday, data, patterns and tipping points

...and some reinforcement of holiday time

Hi all,

It's holiday time, so my newsletter will appear (even more) infrequently. Or, better, I will take a break this coming month from my substack to concentrate on longer writing (and, of course, some swimming, including this one).

Holiday time has profound consequences, not only for those on holiday but also for those at work. It is getting more relaxed, and I always feel more productive when everyone is away. What surprises me is that people who are a whole year old and in a specific pattern can abruptly halt that pattern (e.g., stop working), go on holiday with the family, and then return to the old pattern. This holiday break may also be part of the pattern (and holidays often develop according to certain patterns).

That pattern is that everything is mixed: I tend to do work when I am off and the other way around. I am always working. Or you could state that I always find time to spend on hobbies, family and friends (but you would have to ask them). It depends on what works for you and your reinforcing stable pattern. I am curious, so I always check my mail. And I hate to have it piled up after a three-week holiday. It's better to do that part in the early morning when the rest of the family is still asleep. However, patterns differ based on habits, culture, preferences, et cetera. So, this only works for some. And that is a nice bridge to the first point I want to make in this newsletter. About tipping points and the challenges we have. Especially social tipping points (STPs). New research (see here) is very critical of the found evidence in the literature about the critical mass for tipping points. You know, the idea that only a minority of people need to change their behaviour to come to societal change (often referred to as ‘25%’ based on this article, stretching to 40%, based on this paper). I already said before that this is too much of a generalisation.

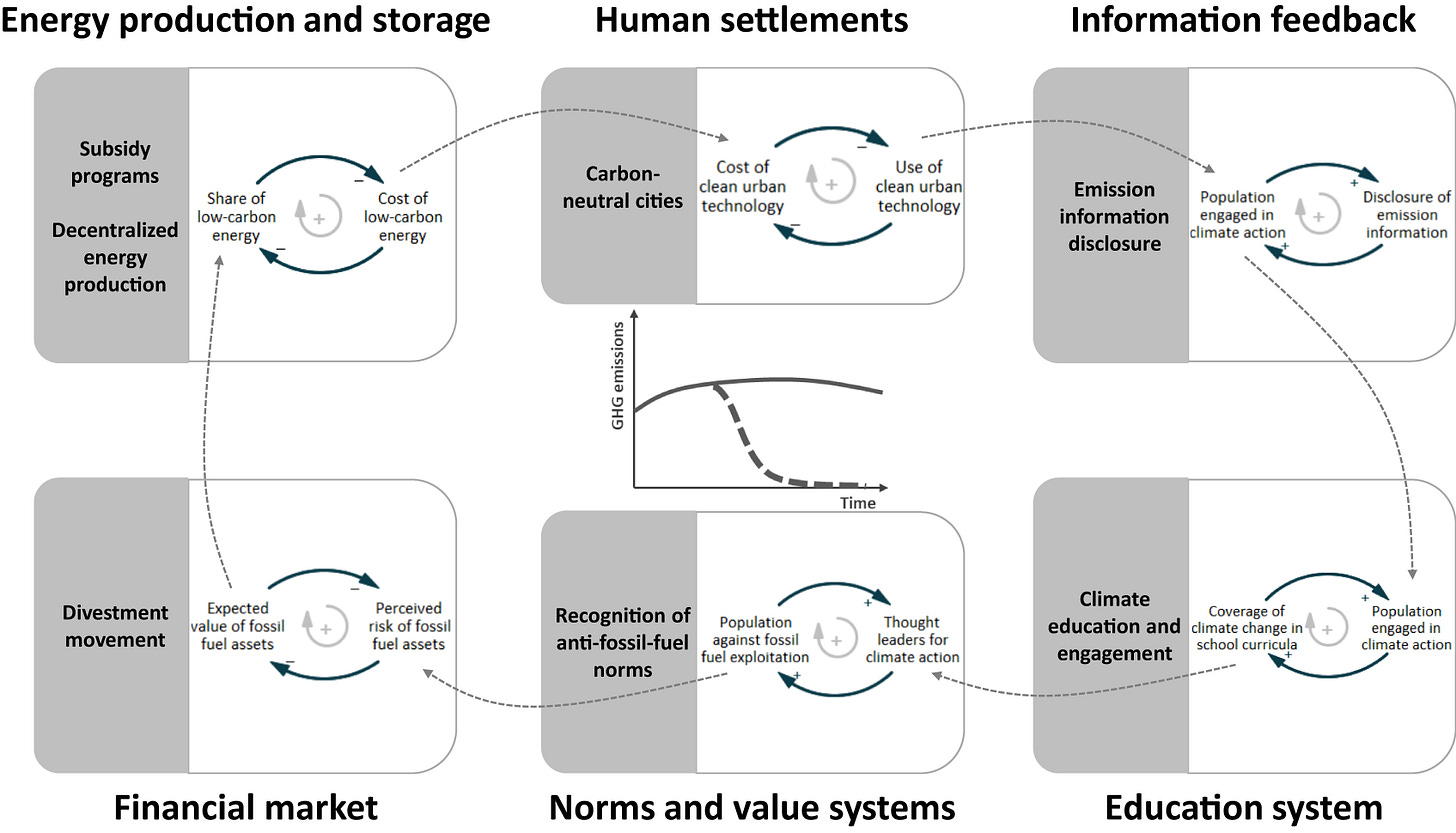

The paper delves (apart from showing that the results on which the findings are based are somewhat meagre) into the interdependencies of systems and the different positive and negative feedback loops (see figure). A systems approach (so, not only looking at one system and isolated interventions) might give a better picture ex ante of what policy interventions can work.

If we translate this back to our holiday time, concentrating only on your longed-for rest during the holiday will work only if you correctly take other variables (family, travel preparation, workload when you come back, and ambitions) into account.

With this in mind, I looked at the UN’s report on the Sustainable Development Agenda and the data dashboard from the System Change Lab.

I also had a reason to look closely at the data. I have been reading Hanna Ritchie's book Not the End of the World. She shows (quite convincingly) some long-term, positive trends. It is not all doom and gloom, I agree. There are fascinating stories about reforestation in Europe, and it is interesting to see the decoupling between economic growth and carbon emissions already happening.

Her long-term data story gives some comfort in the possibility of mankind handling sustainability problems.

However, I am not convinced, at least for four reasons. First, she trusts technological fixes: no words about rebound effects and systems that hinder effective actions. Second, although she starts by saying that degrowth is not the answer, she more or less promotes a lookalike agenda: plant-based diets, less flying, putting a price on carbon and fighting inequality. So, on the one hand she says that system change is not necessary, on the other she gives some proposals that are…system change. How should that be reconciled? Third, I miss the notion of ecosystem and social tipping points. So, even when changes go in the right direction and at a speed we have never seen, it can still be too little or too late. The state of ecosystems is dire, so we need quicker change. I miss that.

The fourth reason is data. It matters quite a lot where you look. Is it long-term, past trends (always a selection), or do you want to say something forward-looking, like the UN report and the System Change Lab’s dashboard? And there, the story is not so optimistic.

The world's getting a ‘failing grade’ on the Global Goals report card was the headline of the press release of the UN report. I don’t know if that is the most mobilising headline these days. But the evidence is quite clear. Only 17% of targets of the Sustainable Development Goals are on track. Nearly half show minimal or moderate progress; over a third have stalled or regressed.

The COVID-19 pandemic, conflicts, and climate crises have exacerbated inequalities, pushing 23 million more people into extreme poverty and leaving over 100 million more hungry.

Developing countries face unprecedented challenges with a worrying economic outlook and skyrocketing debt levels. Of course, there are also some positive trends (reductions in child mortality, HIV infections, the cost of remittances and improvements in access to water, sanitation, energy, and mobile broadband). Still, the report calls it 'glimmers of hope'.

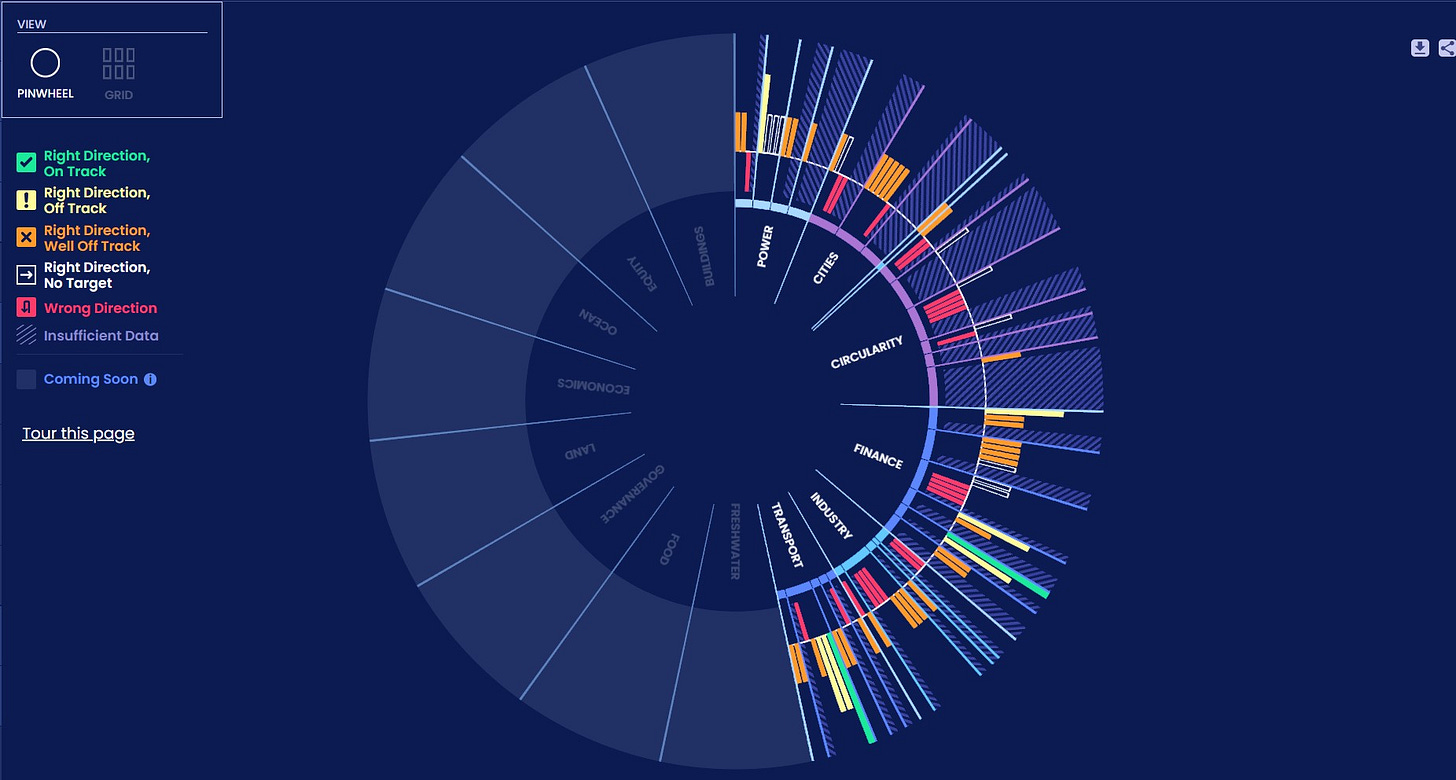

I also looked at the System Change Lab data dashboard. It tries to present the right indicators for system change in one view. For a summary, see the pinwheel below.

Of all the indicators they have (75), 2 (!!) are on track, the rest are off track (6), well off track (34), and in the right direction without a target (10; you can not say anything useful about this), or going in the wrong direction (23).

Optimism based on a more extended time series, as Ritchie does, is great, but it is hard to stay optimistic when you look at the data used to help the system change in the coming decade. The UN outlines that the policy agenda is not about better data or innovation. It is: 🔶 Peace: Conflicts and wars are essential reasons why the SDG agenda stalls (through a lack of international collaboration and the direct effects on the people involved). 🔶 International solidarity. Developing countries urgently require more financial resources and fiscal space. Two root causes are the outdated, dysfunctional, unfair international financial architecture and a lack of capital flows to developing countries based on flawed market logic. That leads to an SDGs investment gap of a staggering $4 trillion annually.

And for me, it is a system change. And that means discussing the fundamental, underlying logic of our economic system. That is not only) because it is my hobby, but also because this data proves it is necessary.

Interconnected tipping points

Of course, I should occasionally discuss tipping points in a newsletter called Tipping Point Economics. New research highlights once again the complexity of tipping points. You can try to enforce them, but they can always be reinforced.

Climate discussions have especially spotlight social tipping points (STPs). To repeat, STPs are crucial leverage points where small changes can lead to significant shifts in societal behaviours, norms, and policies towards, in this case, decarbonization. These points are driven by positive feedback loops that amplify initial changes, propelling the system towards a new state. However, the inherent complexity of social systems means that these feedback loops are not isolated—they are interrelated with other developments, creating a web of interactions that can be difficult to untangle.

Positive feedback loops, while powerful, are often accompanied by negative loops that can dampen or counteract the intended effects. For instance, efforts to shift public opinion towards anti-fossil-fuel norms may be met with resistance from entrenched interests and polarized views, creating a balancing act between progress and pushback. This interplay of reinforcing and counteracting mechanisms adds layers of unpredictability to social tipping processes. It is just like the patterns I started this newsletter with also when you are on holiday, you experience reinforcing and counteracting mechanisms and feedback loops.

Analysing Tipping Points

Studies on STPs often rely on limited empirical evidence and may focus narrowly on specific domains or geographic regions, such as the Global North. This can result in an incomplete picture of the global dynamics of social tipping points and their relevance for diverse socio-economic contexts.

Forecasting social tipping points is tricky, given the interdependencies and feedback loops involved. Traditional models often fail to capture the nonlinear and multi-scale interactions that characterize social systems. For instance, changes in one domain, such as increased climate education, can spill over into other areas, like financial markets and energy consumption, creating cascading effects that are challenging to predict.

Moreover, the timing and intensity of these interactions can vary widely. A small intervention in one context may have a negligible impact, while it could trigger a tipping point in another. The paper's example below shows the interacting systems in the energy transition, which are often not fully considered. This variability underscores the need for a dynamic systems approach that can account for the complexity and interconnectedness of social tipping dynamics.

A Dynamic Systems Approach

To better understand and harness social tipping dynamics, we need a robust framework that integrates both conceptual and empirical aspects. A dynamic systems approach offers a promising pathway. This involves three main components:

Systems Outlook: Mapping out the feedback mechanisms within and across different systems to identify potential tipping points and their interactions helps understand the broader system dynamics and the role of various actors in driving change.

Data Collection and Monitoring: Gather empirical evidence to track the effectiveness of interventions and monitor tipping dynamics in real-time. This requires harmonizing data from multiple sources and scales, ensuring a comprehensive view of the system's behaviour.

Dynamic Simulation Modeling involves using models to simulate potential future scenarios and assess the impact of different interventions. This helps identify high-leverage strategies and anticipate potential counteracting mechanisms.

Policy Implications

Effective policy design is crucial for leveraging social tipping points towards decarbonization. Policymakers need to consider the following:

Holistic Interventions: Policies should target multiple systems and scales, recognizing the interconnected nature of social tipping dynamics. For instance, integrating climate education with financial incentives and technological innovations can create synergistic effects that amplify the overall impact.

Flexibility and Adaptability: Given the inherent uncertainty in forecasting tipping points, policies must be adaptive and responsive to emerging evidence. This involves continuous monitoring and adjusting strategies based on real-time data and feedback.

Engaging Stakeholders: Successful interventions require the active participation of diverse stakeholders, from grassroots activists to industry leaders and policymakers. Collaborative approaches can help align efforts and create a shared vision for change.

Mitigating Adverse Effects: Policymakers must also be mindful of potential negative feedback loops and unintended consequences. This involves identifying and addressing sources of resistance and ensuring that interventions do not exacerbate existing inequalities or create new ones.

In conclusion, social tipping points hold significant promise for accelerating decarbonization, but their complex and interconnected nature makes them challenging to predict and harness. By adopting a dynamic systems approach and designing flexible, multi-faceted policies, we can better navigate the path towards a sustainable and low-carbon future.

Have a lovely holiday; hopefully, you can achieve a personal positive tipping point!

Be nice,

Hans