#22 Different ways to look at Bullshit (jobs)

When an economy becomes too complex, useful work drowns in bullshit

Hi all,

I had a column last week in the Dutch Magazine Vrij Nederland about bullshit tasks (in Dutch). Some people were offended by my claim that some tasks, and sometimes jobs, did not add any value. I can understand that. But it is not the fault of anyone in particular. Bullshit tasks or jobs are part of the system! Especially bullshit tasks. You can have a meaningful job but still have things to do that do not add value. I also have bullshit tasks. Or, even more so, you could discuss the true value added of writing and researching. It is (as always) what angle you take at how to define the bullshit there is.

Of course, my column was a short version of the longer-run argument you can make about useless jobs. The point I made was that, due to the increased complexity of organisations, functions and the need to control everything (in a bureaucratic sense), every job includes more administrative, process and coordination tasks that do not deliver any value to the client or customer. It only helps organisations stay in control of different aspects. It is part of increasing complexity. In general, you can distinguish three kinds of bull-shit work:

(1) The David Graeber-type bullshit jobs: Based on his book (and essay), he was the one that introduced the term bullshit jobs to a broader audience. In his definition, jobs are where even the worker cannot justify what he or she is doing. The people who occupy that job are generally less satisfied with it or at least doubt the added value. According to Graeber:

“a form of paid employment that is so completely pointless, unnecessary, or pernicious that even the employee cannot justify its existence even though, as part of the conditions of employment, the employee feels obliged to pretend that this is not the case” (source: Graeber, 2018)

In the book, he proposed an answer that accused the financialization of social and economic relationships as a form of unjustified power. This question has been addressed, to some extent, by social science research, finding mixed results in terms of what should be reckoned as bullshit jobs and how people view their jobs. The Graeber claim of 40% bullshit is not completely underpinned.

(2) Jobs that are located in firms that don’t add societal value: You could also call these bullshit firms. These are firms where you could question if the products and services they produce add any societal value. Two things can be distinguished here: (1) firms that, if we measure correctly, do not add any societal value and (2) normative judgment if it fills any societal needs.

The first point relates to a previous post, where I discussed the sustainability of businesses and what profits they would make if we considered all the negative side effects of production. Or, in other words, if the integrated value (Financial value + Social value + ecological value) is negative, the job can be called (from a societal perspective) bullshit. Whatever the people do.

It can also be the other way around. A job in a company that creates societal value can be useful there (for instance, a management assistant or a janitor), while this is not the case in a destructive company. There is a well-known story about President John F. Kennedy, who encountered a janitor during a visit to NASA. When asked what he did for NASA, the man replied: "I’m helping put a man on the moon." This story beautifully illustrates that if a company's mission is valuable, everyone within that organization can contribute. It then matters less whether you're an administrative worker or a manager; your work makes sense because it contributes to the whole.

The second point can be related to the degrowth and post-growth literature. What jobs (or economic activity) are needed in society? Essentially, the answer to this question in the post-growth literature is that jobs that produce basic needs (food, public services) and jobs with a low ecological footprint. As we have said in our outlook:

The supply shift involves producing and consuming products with a diminished environmental footprint, employing circular economy practices centred on product durability, reusability, and more efficient resource cycles. Instead of buy-and-dispose, it emphasises using sturdy, locally sourced products, encouraging repairs, and fostering sharing. This shift could impact productivity and employment, particularly enhancing production methods and repair services. Decreased resource demands will prompt employment shifts away from sectors involved in resource extraction. Overall, this shift would result in fewer products sold due to enhanced durability and repairability and increased reuse or sharing, thus potentially impacting economic growth.

Source: Triodos Bank, 2024

This gives a more nuanced perspective on the point before: it is not only about integrated value but also about the (normative) question of whether a person's job adds something to society.

You can also take the COVID-19 ‘essential workers’ list. I did it for the Netherlands, and then the share of non-essential jobs is 64% (that is not to say that the rest is bullshit, but still….)

Or, as Molesworth et al. (2024) “find a parallel in bullshit consumption at work, to work, and because of work.” They propose that much of our work-and-spend lives might be bullshit: routines that promise status, virtue, freedom, and pleasure but feel meaningless while displacing satisfying experiences of care.

(3) Bull-shit tasks that link to increasing complexity. So, even in firms that do the ‘right’ stuff and people that have fulfilling jobs, more bullshit tasks or overhead tasks come in. This is a general feature of many jobs, where all have more administrative and coordinating tasks besides their primary job. Even new IT tools that should make communication, planning and work more efficient seem unable to do that job properly. Another set of KPIs to fill in, more meetings about streamlining processes, and stand-up about the progress of the latest project. Many office workers will surely recognize this. It sometimes feels like we’re doing our work not to achieve something but to maintain the illusion of productivity.

The problem, therefore, lies not so much with the jobs themselves but with the tasks people perform. Not all the work of a nurse is valuable, and not all the work of a manager is bullshit. But all those meetings, the paperwork, and the red tape detract from the primary process: providing services to people and clients. The more complex the organization and the more rules there are, the more significant the portion of our working time spent answering various internal emails and 'alignment meetings.' A kind of law of more bullshit. And this becomes dangerous when people see that as the goal of their work. I understand that things need to be kept under control a bit. But no matter how well-intentioned, it distracts from the primary task. Bullshit tasks that, like a slowly dripping faucet, soak your entire day with mini functions that distract from the meaningful work.

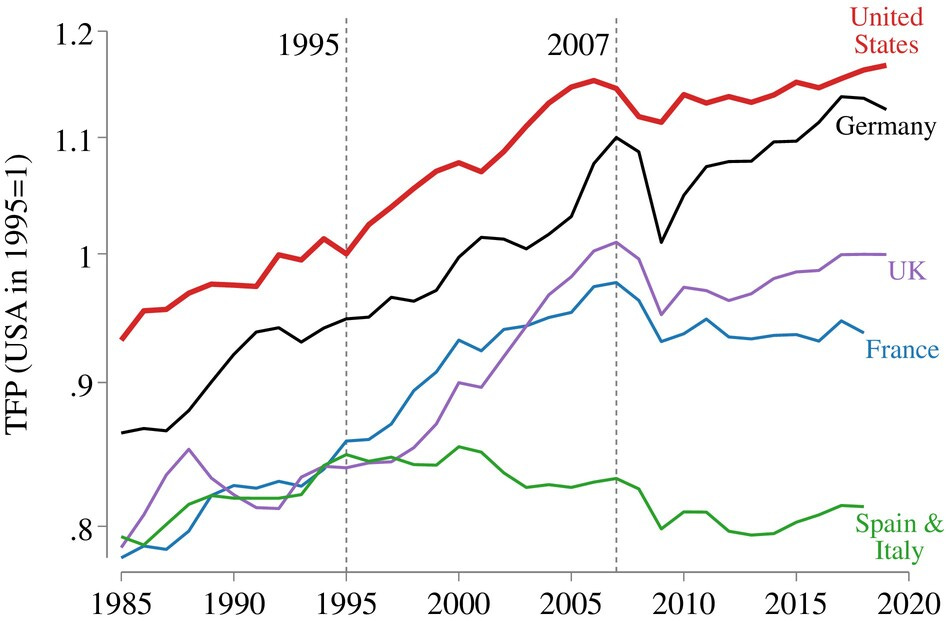

This might also be one of the main reasons why labour productivity in many Western countries is barely increasing. Technology not only ensures that we communicate with each other in even more ways, but it also causes organizations to become ever larger without contributing to something that makes customers happy.

So, there are different ways to look at bullshit jobs. What is, however, clear is that all point in the same direction:

We have the luxury of doing (in rich Western economies) jobs that deliver little financial value. It serves status (from someone), while the value added is questionable.

We do not consider all the value created by jobs (and companies). Value added to a job includes financial value and social and ecological value.

Increased societal complexity increases bullshit tasks.

Hence, the bullshit discussion is an ethical discussion about job satisfaction, job-added value, and complexity. This discussion will become more critical in the coming years. If complexity increases further, how big a part of all jobs can be attributed to handling that part?

Bullshit Graeber style

A lot has been written about the Bullshit Jobs that David Graeber introduced in 2013, and his book in 2018. I am not going to summarise all the theory here. But it is important to note here that the reasoning from Graeber comes from the fact that all productivity gains did not end up in us working less (also referring to Keynes's letter to his grandchildren; see also my previous post on that topic).

Graeber’s notion of bullshit jobs effectively considers some jobs to be created due to some hidden intention, distinct from the positive discourse in which the jobs exist. Graeber proposes a taxonomy of bullshit jobs along five categories:

1. Flunkies, who serve to make their superiors feel important, “Flunky jobs are those that exist only or primarily to make someone else look or feel important” and are compared with feudal retainers;

2. Goons who act to harm or deceive others on behalf of their employer or to prevent other goons from doing so, e.g., lobbyists, corporate lawyers, telemarketers, and public relations specialists . “People whose jobs have an aggressive element, but, crucially, who exist only because other people employ them”;

3. Duct Tapers temporarily fix problems that could be fixed permanently, e.g., programmers repairing shoddy code, and airline desk staff who calm passengers with lost luggage. “Duct tapers are employees whose job exists only because of a glitch or fault in the organization; who are there to solve a problem that ought not to exist”;

4. Box Tickers, who create the appearance that something useful is being done when it is not, e.g., survey administrators, in-house magazine journalists, and corporate compliance officers: “Employees who exist only or primarily to allow an organization to be able to claim it is doing something that it is not doing”;

5. Taskmasters, who create extra work for those who do not need it, e.g., middle management and leadership professionals. “Taskmasters fall into two subcategories. Type 1 contains those whose role consists entirely of assigning work to others. This job can be considered bullshit if the taskmaster herself believes that there is not need for her intervention, and that if she were not there, underlings would be perfectly capable of carrying on by themselves [. . . ]. [Type 2] are taskmasters whose primary role is to create bullshit tasks for others to do, to supervise bullshit, or even to create entirely new bullshit jobs”.

Graeber indicated that among all the categories of workers, the least likely to report that their jobs were bullshit were business owners and everyone else in charge of hiring or firing.

Numerous papers go into the claims that are bullshit jobs after all, if not all, work with poor well-being is useless, classifications, taxonomies, et cetera.

I liked the recent paper by Gauthier that builds an economic model to explain bullshit jobs. His paper, "The Economics of Bullshit Jobs," seeks to provide an economic model to understand the existence and persistence of these jobs. Gauthier builds on Graeber's foundation, acknowledging the substantial empirical evidence suggesting that a notable percentage of jobs could be classified as bullshit. Studies show that anywhere from 10% to 40% of jobs may fall into this category, reflecting widespread dissatisfaction and perceived social uselessness among workers.

Gauthier's approach introduces a model that combines high- and low-skill labour dynamics with the specific incentives of middle management. The model proposes a scenario where middle managers, who play a crucial role in large organizations, may create or maintain bullshit jobs to expand their control and justify their positions. This results in a situation where high-skill, well-paid jobs contribute little to actual productivity and might even be detrimental, while low-skill jobs compensate for this inefficiency.

The paper highlights several key points about the nature of bullshit jobs. First, these jobs often require significant education and are well-compensated, which paradoxically contributes to the dissatisfaction of those holding them. Workers in these roles frequently feel their work is pointless and detrimental to the organization. Moreover, the prevalence of bullshit jobs suggests that the issue is not due to the incompetence of workers but rather systemic issues within organizational structures driven by the self-serving interests of middle management.

Further, Gauthier’s analysis aligns with Graeber's theory that the financialization of labour relations contributes to the proliferation of bullshit jobs. Financial incentives lead managers to create unnecessary roles, reinforcing their power and control within the corporate hierarchy. This situation creates a paradox where efficiency is ostensibly a goal, yet many roles exist solely to serve the interests of those in power.

Although tempting, I think there is more to it.

Useful activities

As I said before, judging the usefulness of workers’ activities is also a type of bullshit alerting. On the internet, you can find numerous lists of completely useless products you can buy. One of my favourites is handerpants (underwear for your hand), but I also like the goldfishwalker, banana slicer or the shoe umbrella.

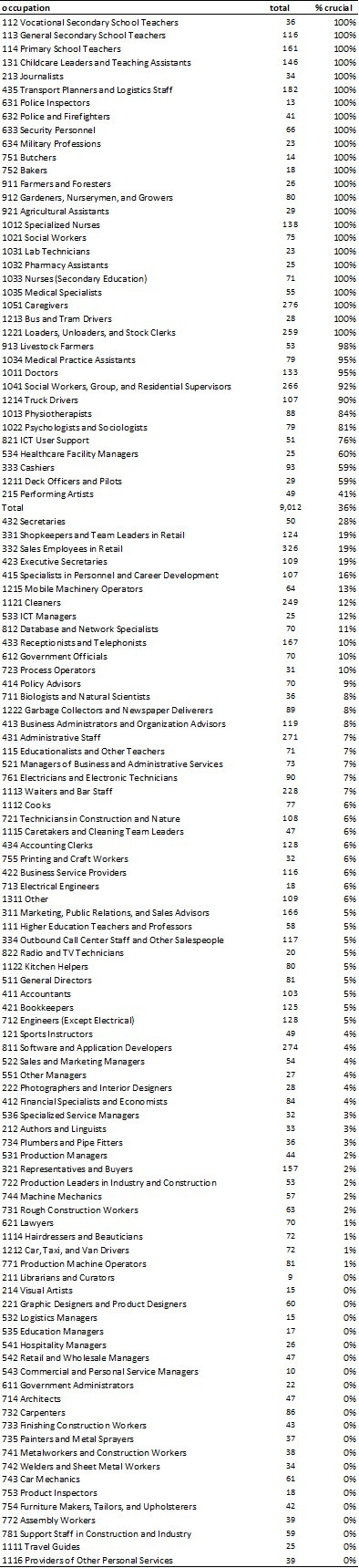

Remember the lockdown days when the government told us only to buy "essential" goods and do "essential" work? In the Netherlands, it led to some interesting realizations about what we need and could easily do without. Below is the list that was published by Statistics Netherlands in 2020. It is interesting to see that, on average, 36% of jobs are seen as crucial (total), but it differs quite a lot per sector (see below). That means that 64% is non-essential. Is that all bullshit, then? Not per se. This list is not what we think adds value to society but what is necessary to keep an economy running during a pandemic. A different perspective.

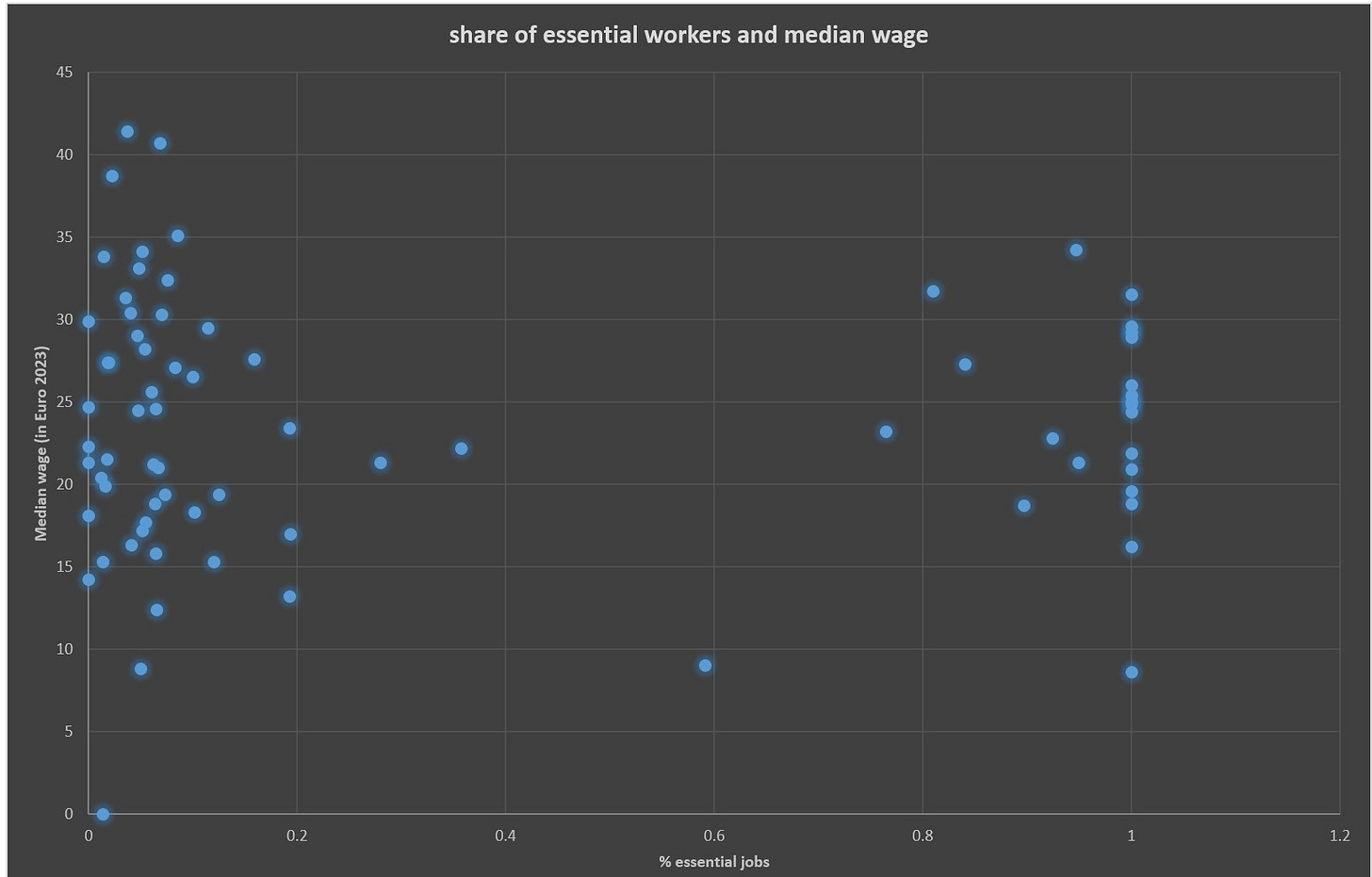

I also used the average wage data for these different occupations if I could see any link. Because in (simple) economic terms, you might expect that more crucial jobs should be paid more. The answer is (as expected): there is no clear connection. Of course, these data should be corrected for differences in age, educational attainment, etc. But even then, I doubt whether we could see a connection.

Of course, this was crucial in COVID-19 times, not applying the abovementioned lens about degrowth or societal value creation. I don’t want to go into all the degrowth stuff about useful jobs. I came across the paper of Molesworth et al (2024) discussing the relationship between bullshit jobs and bullshit consumption.

They begin arguing that during the lockdown, many of us discovered that a lot of what we considered essential was just "bullshit"—things that we spend time and money on but don't need or enjoy. Before the lockdown, we were caught in a work-and-spend cycle. We worked hard to earn money, which we then spent on things we thought would improve our lives. But, as it turns out, a lot of this consumption is just a way to cope with the stresses of work. For example, many realized they didn't miss buying coffee or snacks during their workday. Without the routine of going to the office, these purchases seemed pointless.

During the lockdown, people had more time to think about their lives and their needs. They found that they had more time and money without the daily grind of commuting and office life. They didn't need to buy as much and could focus on things that truly mattered to them. Some examples from the study include:

Cooking at Home: Instead of relying on ready meals or eating out, people started cooking more at home and enjoyed it.

DIY Projects: With more time, people took on DIY projects and found satisfaction in caring for their homes.

Quality Time: People spent more time with their families and discovered they didn't need expensive vacations or outings to enjoy life.

The lockdown highlighted the importance of care—both for ourselves and others. Without the distraction of bullshit consumption, people engage in more meaningful activities like reading, exercising, and learning new skills. They also became more thoughtful in their consumption, buying things that genuinely brought them joy or served a practical purpose.

The big takeaway from the lockdown is that much of our work-and-spend lifestyle is bullshit. When we're not caught up in the rush, we realize we need less than we thought. This leads to a more fulfilling life focused on meaningful activities and caring for ourselves and others. The authors suggest that by "cutting the bullshit," we can create a society that's not only more satisfying but also more sustainable.

So, next time you mindlessly buy something or feel stressed about work, remember the lessons from the lockdown. Focus on what's truly important, and don't be afraid to cut the bullshit from your life.

Complexity and jobs

A last lens on bullshit that I want to use is on the relationship between societal complexity and jobs. The relationship between complexity in society, complexity in work tasks, and productivity is multifaceted and interdependent. Understanding this relationship requires examining how each element influences and is influenced by the others. Complexity in society refers to the diverse, interconnected, and often unpredictable nature of social structures, systems, and interactions. Technological advancements, globalization, cultural diversity, economic systems, and regulatory frameworks contribute to this complexity. As society becomes more complex, work tasks often require specialized knowledge, adaptability, and coordination among various stakeholders. Of course, in my world, it relates to the polycrisis narrative.

Of course, you could argue: hey, is that not almost the same as the Graeber argument that technological advancement leads to more bullshit in jobs instead of job displacement? This has also been observed in recent economic research: technological advancement leads to job displacement, but that is more than offset by creating new jobs (see, for instance, this overview paper).

But this is not what I mean. My argument here is that the fraction of time all workers spend on “bullshit” tasks (duct-taping, box-ticking and task mastering) to at least get something done. This might explain the slowdown of productivity growth in rich countries, which is now widely documented (see here).

We simply don’t know what causes it. So, this is also only a new hypothesis rather than an empirical fact.

So, a few suggestions.

The first is the policy/regulation perspective. It is tempting to think that increasing regulations and policies that are well-documented in political sciences (see, e.g., here) leads to more complexity and less efficiency. This is labelled as policy growth. Policy growth leads to red tape and more bullshit, also (or specifically) in jobs classified as essential. More policy growth (for whatever reason - internally or externally driven), can be an explanation for poor performance by bureaucracies and increasing bullshit tasks. This restricts itself to civil servants and all confronted with new regulations (good for box tickers!).

The second option is an innovation perspective, which is related to limits to innovation (see this paper). There are three reasons for an Upper Limit to Technological Development: Fewer benefits from complexity, higher maintenance costs, and catastrophes that disrupt progress. This boils down to jobs: if more in what you have to do is maintenance or dealing with complexity, it is less about doing things smarter or better. This means more (kind of) bullshit, less serving clients.

There is more to think of. But that there is some relationship between societal developments (complexity, technology) and bullshitting seems obvious.

That’s all, thanks for reading.

Be nice,

Hans

“if the integrated value (Financial value + Social value + ecological value) is negative, the job can be called (from a societal perspective) bullshit.”

This point really resonates, to consider the true externalities of a business but apply it to the job itself!