#6 Why and how would you accelerate when already sprinting at your maximum speed?

Still thinking we need growth is denying progress (and ageing)

Hi all,

One of the challenges of advancing in age is that participating in your favourite sports becomes... different.

I used to engage in triathlon, but I ceased doing so several years ago due to permanent injuries that have rendered running impossible. What remains are cycling and swimming. At present, I am rebuilding my swimming fitness for the first time in years through group training. After each session, I am reminded that achieving greater speed is now more challenging than ever. I've also accepted that comparing myself with much younger swimmers is futile. While maintaining long-term training and endurance remains feasible, recovery takes longer.

Nevertheless, the silver lining is that I derive more enjoyment from it. I've come to realize that the pursuit of greater speed is no longer my top priority. Finding pleasure in the exercise, maintaining a sense of fitness, and sharing these activities with others have become the true sources of joy.

This lengthy preamble draws a parallel with the state of most Western economies. They are not only ageing demographically but are also growing older in terms of economic vitality. Despite this, we expect them to perform as if they were in their prime and measure that as their health. However, how can one accelerate when sprinting (or swimming) at full speed? Are we not denying all our progress (just like I do once in a while)? And why do we keep thinking that more economic growth says something about the health of our economy? I think that clinging to the growth model says more about our inability to live up to our adult phase. It is like me, that still wants to compete with others that are twenty years younger.

What brought me to this consideration? One is a research paper about 90 years after Keynes’ letter to his grandchildren. Two: the fact that, while as our economy operates at full throttle, we see meagre growth. Three: the report on Dutch demographic development as published a few weeks ago.

In all this, the realization that we must begin contemplating a stationary, post-growth economy as a new reality. Growing old prompts us to adjust to a new reality rather than attempting to outpace the younger generations. Don’t count on the speed; enjoy the complacency.

In the end, you’ll find some news.

Enjoy

90 years after Keynes

A lot has been written about Keynes’ letter to his grandchildren 90 years ago (Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren). In this letter, he delved extensively into the potential transformation of the economy once the foundational struggle for subsistence had been conquered. Keynes astutely identified three overarching trends that he anticipated would come to define the socio-economic evolution of advanced countries within the framework of individualistic capitalism:

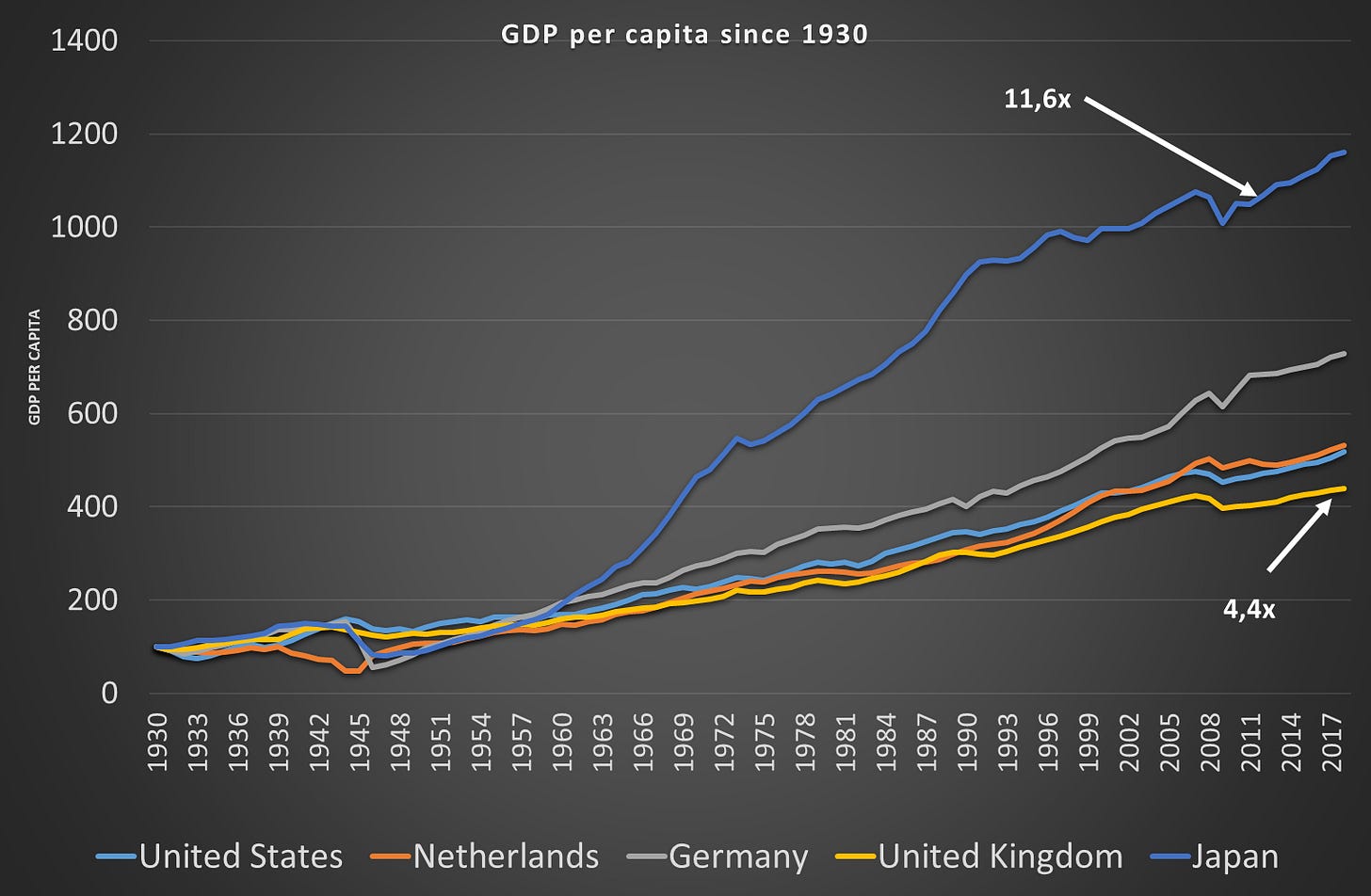

Persistent Technological Advancements and Capital Accumulation: Keynes foresaw these as the primary catalysts behind exponential growth in economic possibilities, continually propelling the economy forward. He expected material prosperity to increase 4 to 8-fold.

Gradual Shift in Life Choices: He also predicted a gradual, widespread shift in life choices, moving away from an overemphasis on work as society progressed. This transition would enable individuals to explore a more balanced and multifaceted approach to life.

Evolution of Societal Morality: Keynes envisioned a transformation in the prevailing code of morals in societies nearing a stationary state of zero-net capital accumulation. Here, the economic problem would have been solved, and people would predominantly embrace a lifestyle centred around leisure rather than being compelled to engage in disutility-yielding work (sounds familiar right, when you read post growth literature).

Keynes's insights offer a profound perspective on the potential evolution of economies and societies beyond the immediate struggles of subsistence.

Keynes proposed that society should reimagine its pursuits and suggested that a reduced workweek of 15 hours could suffice for individuals to achieve contentment. Therefore, he acknowledged that societal values could transition alongside economic change.

Keynes’s optimism has proved correct regarding today’s material possibilities in rich countries as the “advanced guard” of mankind, which is certainly not true for humanity. In the UK, GDP per capita has increased 4.4 times, in Japan 11.6 times (see figure).

The enduring prevalence of unchecked materialism in the lives of most workers, despite Keynes's expectations and aspirations to the contrary, should be understood within the broader context of path-dependent social evolution and prevailing individualistic and materialistic worldviews. Even geopolitical factors appear to encourage the influential interests of highly concentrated financial power in perpetuating the relentless demands of labour.

Financialisation and escalating debt levels serve as one explanation for the ever-increasing pursuit of more. Additionally, insatiable relative needs and ratchet effects drive this phenomenon, as does society's pervasive and widening inequality. While there are individuals for whom working more remains a source of pleasure and a chosen way of life, they constitute only a minority.

Hence, we are still in a growth mindset.

Stagnant pain

But this growth mindset is increasingly posing a problem. And I think people nowadays quite often miss that point. Take central bankers and the inflation discussion.

Central banks hiked interest rates more aggressively than ever before. Due to the higher interest rates, borrowing and saving decisions will take a different course. In theory, higher interest rates will lead consumers to save more and borrow less. For investments, the credit channel operates through the user cost of capital, representing business capital costs. Higher interest rates, with some delay, increase capital costs. These higher capital costs negatively impact investment decisions. The resulting decrease in demand for capital goods subsequently leads to reduced production, resulting in lower employee demand. This, in turn, results in higher unemployment, leading to lower (real) wage growth. Consequently, available household income decreases, and private consumption declines. Private consumption is also negatively affected by diminishing capital gains and losses (the asset price channel). These are the first-round effects.

Reduced consumption and investment lead to declining employment (and possibly lower profits) and reduced economic activity, a decrease in demand for goods and services, and fewer opportunities for producers to pass on cost increases. All this would lead to lower inflation rates.

That is theory. Practice (up till now, at least) is completely different. Unemployment is still very low in many economies, and the US and European Union economies are producing above their long-term potential (see figures).

This situation contradicts the theoretical framework mentioned earlier, highlighting that policymakers are still grappling with the fact that sustained economic growth is no longer the norm. Despite economies operating at full potential, Europe is on the brink of stagnation. Consequently, if interest rates decreased in Europe, the anticipated impact on overall economic activity would be modest at best. Attempting to stimulate an economy already operating at full capacity would primarily result in wealth redistribution and escalating asset prices. One might argue that the motivation for such a move could be to prolong the credit (super-)cycle, concealing the unsettling truth that beneath a significant amount of debt lies no genuine claim on current or future economic activity. (Shh, let's keep this between us.)

While we can certainly hope for a miracle, such as a sudden surge in productivity growth, such developments are unlikely to materialize instantly. What appears to be working, though not welcome news, is that interest rate hikes are causing further investment declines. Given that we require more investments, particularly in research and development (R&D), to foster productivity growth, this presents a considerable challenge. There is much more to delve into on this topic, but I'll save that for another occasion. Now, let's shift our focus to demographics.

A new demographic reality

A few weeks ago, there was a report in the Netherlands about demographic development until 2050. The title ‘moderate growth’ says it all. It says that we need growth, but should not expect too much.

What struck me most was the quote (translated):

“Economic growth is necessary to maintain overall prosperity. This understanding applies not only to households but also to the affordability of public services such as healthcare, education, and security, as well as the preservation of social insurance programs that mitigate income inequality. To sustain or even enhance overall prosperity, the public system must withstand a prolonged period of population aging. These services need to be funded through taxes or contributions, and the broader the base of support (income from capital or labour), the lower the burden per capita. Sustainable economic growth, which takes into account environmental and climate impacts, is closely tied to expanding this support base.” (page 199)

A typical within-system argumentation: The economy must grow since our system is based upon growth to pay for public services and ageing. A circle-reasoning is presented as a scientific fact. Based on this, the commission concludes that it is better to have some population growth (in the case of the Netherlands migration). I have nothing against migration. But I have something against this reasoning. As stated by Keynes more than 90 years ago, we have a choice.

It is a choice: keep struggling upstream or reimagine.

I did, on purpose, not touch upon the ecological impossibilities of having continued economic expansion (of course, it is impossible; I will come back to that later, but see, for instance, the physics’ take on it here). This newsletter is foremost stressing the fact that we need to get used to a new economic reality AND that continued economic growth is not going to happen simply because we want to. It is like trying to swim upstream on a waterfall (and getting older). A reality where growth is no longer easy to get and also not necessary for the well-being of many people. Like myself, growing older and still training, progress gets a different meaning. It requires different behaviour. Another quote in Keynes’ letter on this:

“The pace at which we can reach our destination of economic bliss will be governed by four things-our power to control population, our determination to avoid wars and civil dissensions, our willingness to entrust to science the direction of those matters which are properly the concern of science, and the rate of accumulation as fixed by the margin between our production and our consumption; of which the last will easily look after itself, given the first three.”

It's quite straightforward. We continue to consume excessively, produce in excess, engage in too much conflict, and only population growth appears to be tapering off.

For those of us residing in affluent Western nations that have witnessed significant advancements over the past ninety years, it's high time we begin reimagining the concept of progress. Drawing a parallel with my swimming experience, perhaps we should derive more enjoyment from maintaining a steady state when we can no longer push for greater speed. I acknowledge that this necessitates a certain degree of reimagining, beginning with our capabilities and aspirations.

In the news

Farmers protesting: Farmers are being burdened by debt, squeezed by powerful retailers and agrochemical companies, battered by extreme weather, and undercut by cheap foreign imports, for years now — all while relying on a subsidy system that favors the big players. However, it's evident that we confront a more profound systemic problem. There's a pressing issue of lobbying by influential entities that manipulate regulations to their advantage, often leaving farmers, who genuinely face challenges, to carry out their bidding. This issue is intertwined with climate change, a crisis partially triggered by our current agricultural practices, which are projected to inflict even more severe consequences in the future. Furthermore, we face a global food system that imposes an environmental cost of $3 trillion annually, alongside additional health expenses of at least $11 trillion

A comprehensive report by the Food System Economics Commission to solve the F&A problem:

Shifting consumption patterns towards healthier diets

Repurposing government support for agriculture

Allocating revenue from new taxes to support food system transformation

Innovating to enhance labor productivity and livelihoods, particularly for vulnerable food system workers

Expanding safety nets to ensure food affordability for the poorest

Carbon brief analysis on how China works on the energy transition:

China made massive investments in solar power, electric vehicles (EVs), and batteries in 2023, with clean-energy investment increasing by 40% to 6.3tn yuan ($890bn), driving all of the country's investment growth.

China's $890bn investment in clean energy rivals global investments in fossil fuels, contributing significantly to the economy, and accounting for 40% of GDP growth in 2023.

Clean-energy sectors in China have become the largest driver of economic growth, helping the country exceed its GDP target.

This demonstrates that, with public funding and commitment, an energy transition can replace fossil fuels and serve as an example for other nations.

Ambitious agenda from European Central Bank:

1️⃣ Assessing the impact and risks of transitioning to a green economy.

2️⃣ Examining the increasing physical impact of climate change.

3️⃣ Analyzing risks from nature loss and degradation.

This last point is especially important to avoid carbon tunnel vision.

These efforts aim better to understand the changes in our economy and financial system and support the green transition.

That’s all for this week.

Take care.

Hans