#21 The Externalization of Internalities

Growth can be good, but enoughness is better

I am on the journey to the degrowth and ecological economics conference in Pontevedra, Spain. I was preparing (two days in the train for the conference (a panel on investing in degrowth and presenting a paper in post-growth finance), and I was thinking about the underlying assumptions that differentiate ecological economics and degrowth from neoclassical economics.

It seems reasonable to think about it. Not to polarise but to be aware of the difference between underlying and standard economic assumptions.

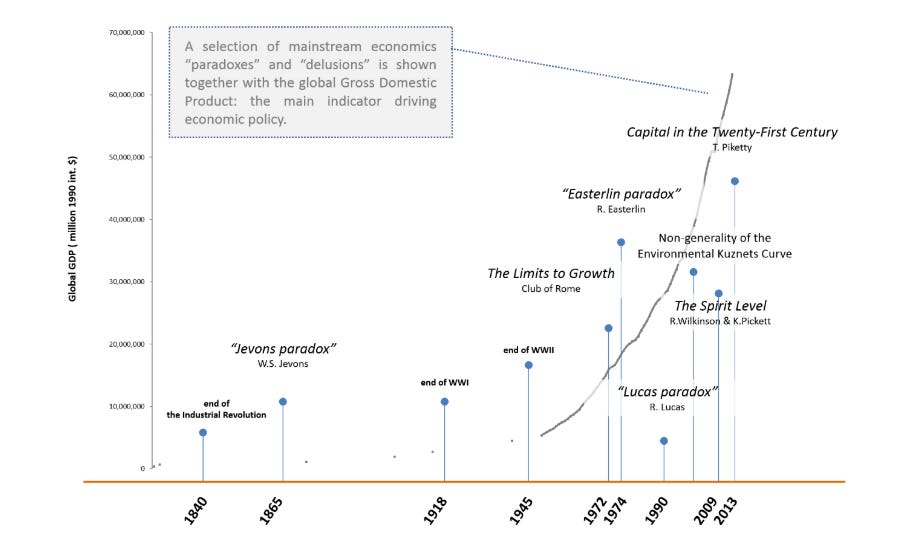

Some core myths and paradoxes in economics are overlooked or ignored. I like Coscieme’s et al (2019) representation, with some paradoxes and delusions.

On a slightly different abstraction level, I want to add a few:

Markets tend, through trade and price adjustments, to an equilibrium

Substitution between capital, labour and nature is (to some extent) always possible. Consequently, there is no limit to growth

Outcomes of market interaction are neutral, (re-)distribution is up to politics

By aggregating micro preferences and actions, we get macro preferences and optimal wellbeing

A market-based economy is based on firms making profits and competing. Hence, more is always better

And, maybe the biggest assumption of all: we should concentrate our efforts on reducing ‘externalities’.

I will not go into detail now on all of these assumptions. Today is externalities day.

Economists often discuss externalities, referring to all non-priced effects of production and consumption. Essentially, these are all the impacts you experience for free due to the actions of others. This can range from enjoying beautiful graffiti without paying for it to dealing with harmful PFAS in your broccoli. According to market logic, the solution to eliminating adverse external effects is straightforward: ensure that all unintended adverse side effects are priced. This makes harmful actions more expensive and less harmful actions cheaper, leading to more sustainable production. This logic is flawless.

However, despite economists advocating for this policy of internalizing externalities for decades, its success has been limited. Only about a quarter of the largest external effect, CO2 emissions, is priced, and even then, the price is far too low. The most significant success in environmental policy – the phasing out of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) to close the ozone hole via the Montreal Protocol – was achieved through a phased ban on products containing these gases. In other words, it is done by limiting markets and not internalising externalities.

Another assumption remains unchallenged in pricing: maximizing market transactions at the lowest cost and with the highest revenue might reduce adverse effects, but it still doesn't explain why we should pursue this. The link between more profit, more production, and happier people has long been untenable in most wealthy countries.

It took me years to realize this despite it being so obvious. How can we discuss the negative side effects of a system (externalities) when the flaws are inherent in the system itself and in ignoring empirical truths that are now called paradoxes and delusions (for neoclassical economists)? Perhaps we should not talk about internalizing externalities but about externalizing internalities.1

These internalities are part of the current economic paradigm. There is a whole bunch of research discussing their flaws and trying to attack the growth paradigm (for instance this article). Let’s call it the growth paradigm. Growth is the basic underlying assumption underlying assumptions and, based on those assumptions, economic structures lead to the conclusion that economies need to grow. Growth is good, which is essentially the same as Greed is Good…

“There is a primary cause of the Continuous Critical Problems: It is growth. Exponential growth of energy use, material flows, and population against the earth’s physical limits. That which all the world sees as the solution to its problems is in fact a cause of those problems.”

(Source: Meadows and Meadows, 2007)

Internalities can be explained as the theories' underlying ‘preanalytic’ assumptions. Because they are presented as facts, these assumptions are somewhat unquestionable for economists.

The fundamental problem with market thinking is that 'the market' is seen as the central point where wealth is continuously generated, and everything else is 'external'. This leads to pricing everything because market efficiency is the most critical criterion. As a result, we aim to produce as much as possible, assuming it makes everyone happier.

What if we reversed this perspective? Would that be possible? We would not ditch everything that is marketing but concentrate on the underlying assumptions to analyse once again whether this serves our objectives as a society: well-being for all.

Please start with the basics: the nature we depend on, which has intrinsic value and which we are a part of. If we want to maintain (or restore) this, it cannot be an external effect; it must be the starting point of the analysis. It's not hard to imagine that banning further destruction is wiser than setting a price.

Does this mean there should be no market? Is efficiency a dirty word? Not at all. But first, we need to acknowledge which underlying assumptions don't always hold. 'The market' will never solve an ecological crisis. Therefore, stricter boundaries are needed than just pricing. Even if this comes at the expense of economic growth, within those boundaries, growth is fine. Beyond them, it is life-threatening.

A recent article precisely depicts that. A corridor of sustainable outcomes, of ‘enoughness’, relates different elements of society and also shows the complexity of individual (and collective) actions on individual outcomes. Relations of enoughness can be connected to sustainability by expanding them into chains of enoughness, which serve as a conceptual foundation for the sustainable consumption corridor approach (see below).

Essentially, this means setting limits which contradict the current paradigm. However, it is likely the only way to achieve an economy that serves everyone and addresses the core assumptions that impede overall well-being.

By establishing boundaries, collective objectives are prioritised over individual utility. These boundaries acknowledge the limits of substitution: nature and solidarity have thresholds below which they cease to function effectively. Moreover, setting boundaries mitigates rebound effects, which obstruct the path to sustainable outcomes.

The concept of "enoughness" underpins the establishment of these boundaries and is the key to creating a more beautiful world that can thrive for future generations. Setting boundaries is the way forward to externalising internalities.

Overrepresentation of rebounds

In a recent blog, Blair Fix shows how energy and resource efficiency often lead to increased resource use, a phenomenon known as the Jevons Paradox. This isn't just true under capitalism but also holds in the natural world. Whether it's increased efficiency in energy use (coal, natural gas, oil), bitcoin mining, computational speed, or animal biomass efficiency, it all leads to more energy consumption.

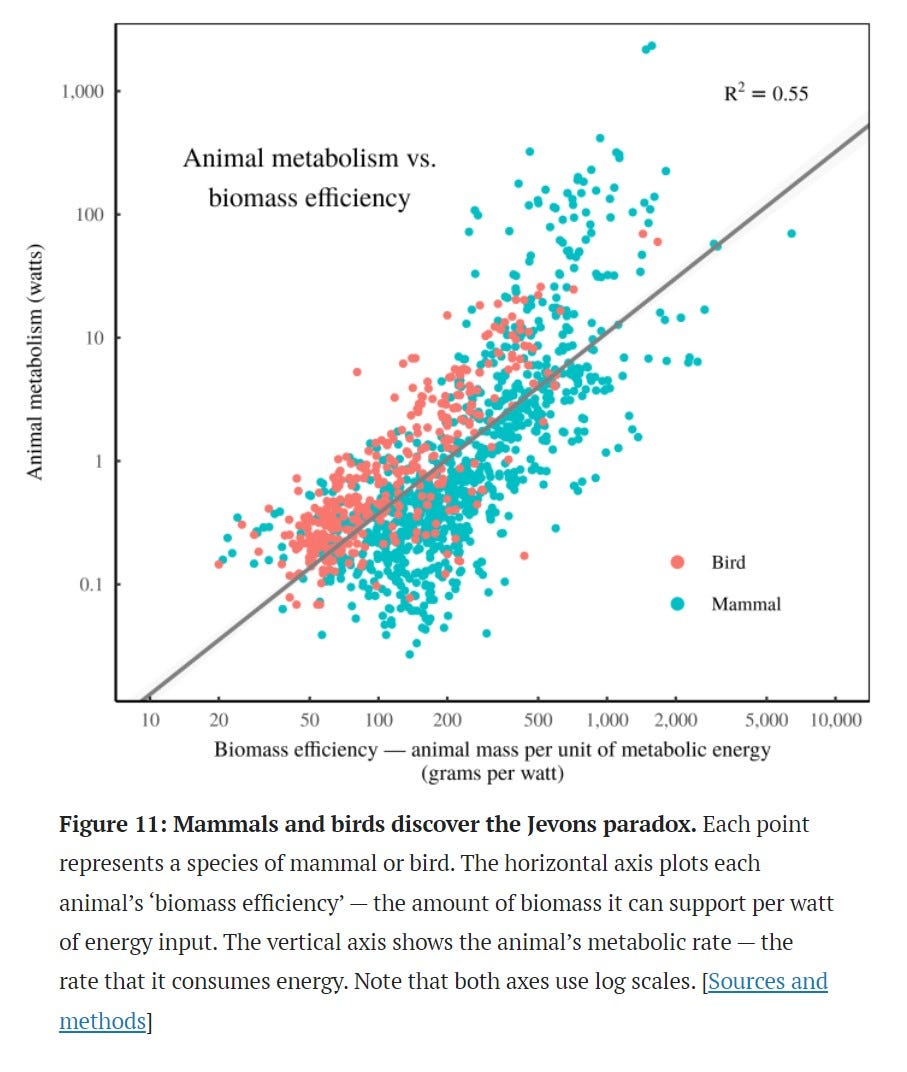

I especially liked his section about rebound effects in nature. Based on a measure of biomass efficiency2, he calculates whether more efficient animals also use less (overall) energy.

To quote:

Now to our question. Is life immune from the Jevons paradox?

The answer is unequivocally no.

Let’s look first at mammals and birds — the warm-blooded species with whom we’re most closely related. Across this group of animals, biomass efficiency varies from a low of 20 grams per watt to a high of 5,000 grams per watt. So if greater efficiency got parlayed into energy conservation, the most efficient animals should consume about 250 times less energy than the least efficient animals. But that is not what we find. Instead, more efficient birds and mammals tend to consume more energy.

His conclusion is that resource efficiency always leads to more energy use without constraints.

This has severe implications for sustainability policies. Even if we are very optimistic about technological development and resource efficiency, without constraining demand, we will not achieve sustainable outcomes. Given the growth paradigm, more will always result because that drives profits. It will lead to expansion, and it will never lead to a natural equilibrium.

We can learn from bacteria, where there is evidence that more efficiency leads to less energy use. Not because they want to but because they are constrained.

What to do, then?

First, impose constraints: To avoid the Jevons Paradox, we must impose constraints on technological expansion. Innovation will not help! It will only lead to more rebounds without constraints. Proactive policies are preferable to reactive measures imposed by disasters.

Second, drastic social changes are required, focusing on expanding public goods, reducing inequality, and limiting conspicuous consumption.

Third, we all know that technological progress and innovation are not neutral (the direction is profit-driven, as I explain here). Shift technological growth towards renewable energy. Although efficiency improvements can still lead to increased consumption, renewables are limited by the sun's energy budget.

The transition to renewables often leads to increased energy consumption, as renewable sources add to rather than replace fossil fuels. Addressing this requires strict policies against fossil fuel efficiency improvements. Stop funding fossil fuel efficiency projects and redirect investments to renewable energy development to combat the paradox. This may seem extreme, but it's necessary to prevent efficiency gains from backfiring.

Enoughness

When it comes to sustainable development, a buzzword you'll often hear is "sufficiency". In this paper, it is related to enoughness. But what does that mean? Let's break it down in a way that’s easy to grasp yet insightful enough (talking about enoughness…).

The Big Idea: Enough is Enough

The concept of sufficiency revolves around the idea of "enoughness." It’s about figuring out what amount of resources or consumption is just right—not too much, not too little. Think of it as the Goldilocks principle applied to sustainability.

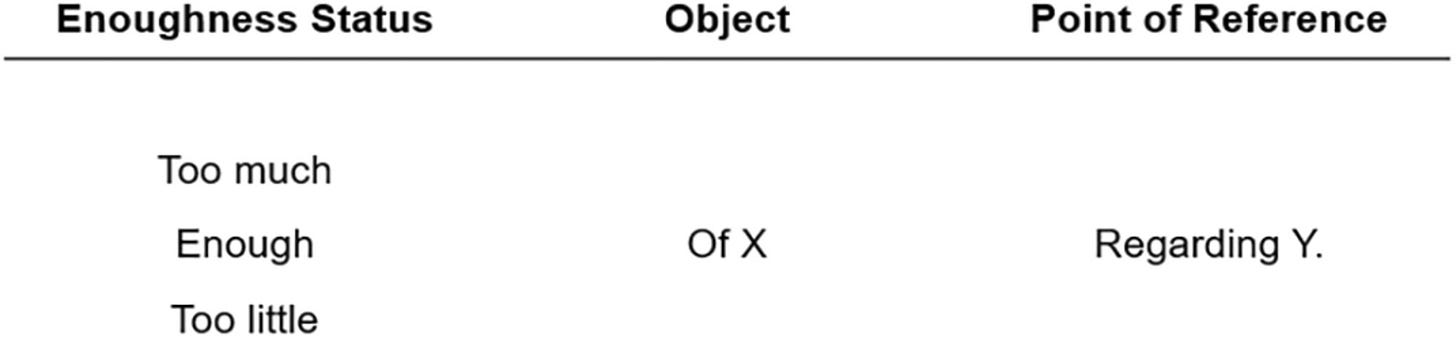

Eric Hartmann’s research paper introduces "relations of enoughness," a framework to make the abstract idea of sufficiency more concrete. By defining what is enough regarding specific needs or impacts, this framework helps us understand and apply sufficiency practically. To externalise internalities and progress on sustainability.

Why Does It Matter?

The world has been on a mission for sustainable development for over three decades, starting with critical milestones like the Brundtland Report, the Earth Summit in Rio and, of course, the Paris Agreement. Despite this, recent reports show we still fall short on many Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). For instance, about half of the 140 targets measured are off track, and over 30% have seen no progress or regressed. I won’t tell you anything new. The typical approach has been green growth—trying to reduce environmental impacts while continuing economic growth. Typically ‘within system’ solutions are within the growth paradigm. Empirical evidence is not enough, and ask a physicist, ecologist or climate scientist if green growth is possible…their answer will be an unequivocal no on a global level. This is where sufficiency comes in, advocating for a balanced consumption and resource use approach.

The Framework: Relations of Enoughness

Hartmann’s framework posits that sufficiency can be boiled down to a simple structure: "enough/too much/too little of X regarding Y." For example, enough energy for a community means not using too much that it leads to environmental chaos and not too little that it hampers growth and development.

By mapping out these relationships, we can identify sustainable consumption corridors—guidelines for what consumption levels are sustainable and equitable. This helps create policies and practices that ensure we don’t overuse or underuse resources.

Let's take a concrete example: carbon emissions. Many countries, especially in the global north, have carbon footprints way above sustainable levels. For instance, the average carbon footprint per person in the US is 17.6 tons of CO2 per year, while the target is 2.5 tons by 2030. Reducing this footprint is crucial to tackling climate change effectively.

Hartmann’s framework suggests we look at individual consumption patterns and adjust them to fit within the "enoughness" corridor. This means finding practical ways to live and consume that significantly reduce emissions—like reducing air travel or improving home energy efficiency.

Broader Implications

Sufficiency isn’t just about environmental limits; it also addresses social equity. For example, ensuring everyone has enough food, shelter, and healthcare to meet their basic needs aligns with the concept of sufficiency. It's about striking a balance where all humans can live decent lives without exceeding the planet's capacity to support us.

In conclusion, enoughness might be a way to externalise internalities: to eliminate the growth paradigm we are stuck in. By focusing on what is "enough," we can develop more holistic and practical approaches to sustainable development, ensuring environmental protection and social equity. So, as we strive for a sustainable future, let's remember that sometimes, less is more.

Thanks for reading!

Take Care,

Hans

I don’t refer here to internalities as sometimes used in the economic literature as (allocative) inefficiencies resulting from public action to account for the reduction of external effects, see e.g. Ellingsen (1998)

biomass efficiency=organism metabolism/organism mass

Mooi stuk, dank!