Hi all,

As my regular readers know by now, I like to do sports. Currently, my objective (or, as my housemates would call it, obsession) is swimming long(er) distances. This means that I try to train three times a week and also do some exercise. When I sport regularly, I feel healthier and better in shape. And sharper at work. Although my objective (some swims in August) is, as I know, completely unimportant, it helps me to have a target and discipline. It does not matter to anyone how fast I swim except for myself.

But with a job and family, it is a struggle to find the time. But it is also a luxury struggle: I have the means to eat healthy, sleep well, and have the mental space to occupy myself with individual (inherently useless) exercise.

As an economist, I conclude from experience that doing sports and living healthy are luxury goods.

And that seems accurate: higher-income groups tend to have better health, a ‘stylised fact’.

However, at least three things complicate the relationship between health and economic progress (see, for instance, this classic article in the Journal of Economic Literature by Angus Deaton or this one from Picket and Wilkinson). Between countries, it matters how rich countries are (as measured by GDP per capita), the quality of institutions, socio-economic inequality, and the quality of healthcare and access to it. Within countries, differences can be explained by income inequality (which determines a large part of lifestyle), access to

I don’t want to discuss all these facets here. I want to restrict myself to a simpler question. What is the relationship between obesity and economic progress in rich countries?

But first, I would like to give you some background on the relationship between economic growth and health in general. The recent, long-run evidence is pretty straightforward. In the long run, higher incomes correlate with a higher life expectancy on average between countries. However, these long-run life expectancy improvements depended on advancing medical knowledge as much as on economic growth that facilitated better nutrition and the provision of health services. Therefore, these health transitions (the effects of medical breakthroughs) also go in waves around the Globe, starting in the rich part and ending up improving life expectancies in poorer countries. So, there is no guarantee that ongoing economic growth will lead to better health.

And this relates to the obesity topic. The overall conclusion on the relationship between economic growth and obesity is clear: Economic growth and obesity correlate. According to this research, over the 40 years 1975–2014, adult obesity prevalence increased at a declining rate with GDPPC across the 147 countries.

Moreover, there is no indication that this trend reverses for higher-income countries (although for some groups, like me, people tend to have the luxury of being less overweight).

The conclusion is, however, necessary. In wealthier countries, people seem to be more overweight, which increases with increased GDP. For instance, in the Netherlands, the correlation between economic growth and obesity is .98, while the correlation between economic growth and (self-reported) happiness is…..-.06 (see also the figure below). In other words, we probably overeat (on average), leading to all kinds of things but not happiness (on average).

This is important. It is a sign of a society entirely out of balance.

As Tim Jackson argues in his book Post growth:

Calorie counting, believe it or not, works through one of the most fundamental laws of physics: the first law of thermodynamics. Carolies are a measure of energy.. Thermodynamics is the study of energy transformations. The calories we consume are transformed in physical processes within our body. but the energy is always conserved along the way. […] Whatever is left from the calories we consume will be stored in the body as fat (a form of chemical energy). This is where the first law comes in. If your calorie intake exceeds the basic maintenance energy needed to keep you alive plus the energy you exert through physical activity, the excess energy is stored in the body, usually as fat.

Source: Tim Jackson (2021), p 70.

The link with economic metabolism is so apparent. As long as there is a lack of calories (or the fulfilment of basic needs), growth is good for the financial system (as long as it fits within its natural environment). It derails when basic needs are fulfilled, and growth becomes a goal. To quote Tim Jackson again: More is only better when not enough (Jackson, 2021, p. 71). However, the economic system is not built in such a way. We are seduced to consume more fat, salt, and sweet food, which we like most. Ultra-processed food helps societies become more obese and helps the food industry earn money.

There is no easy way to stop this. An economic system wants to expand; that is its natural state. And for humans within that system, it is difficult to resist that. We all know from ourselves that balance, not growth, is the essence of personal and societal prosperity.

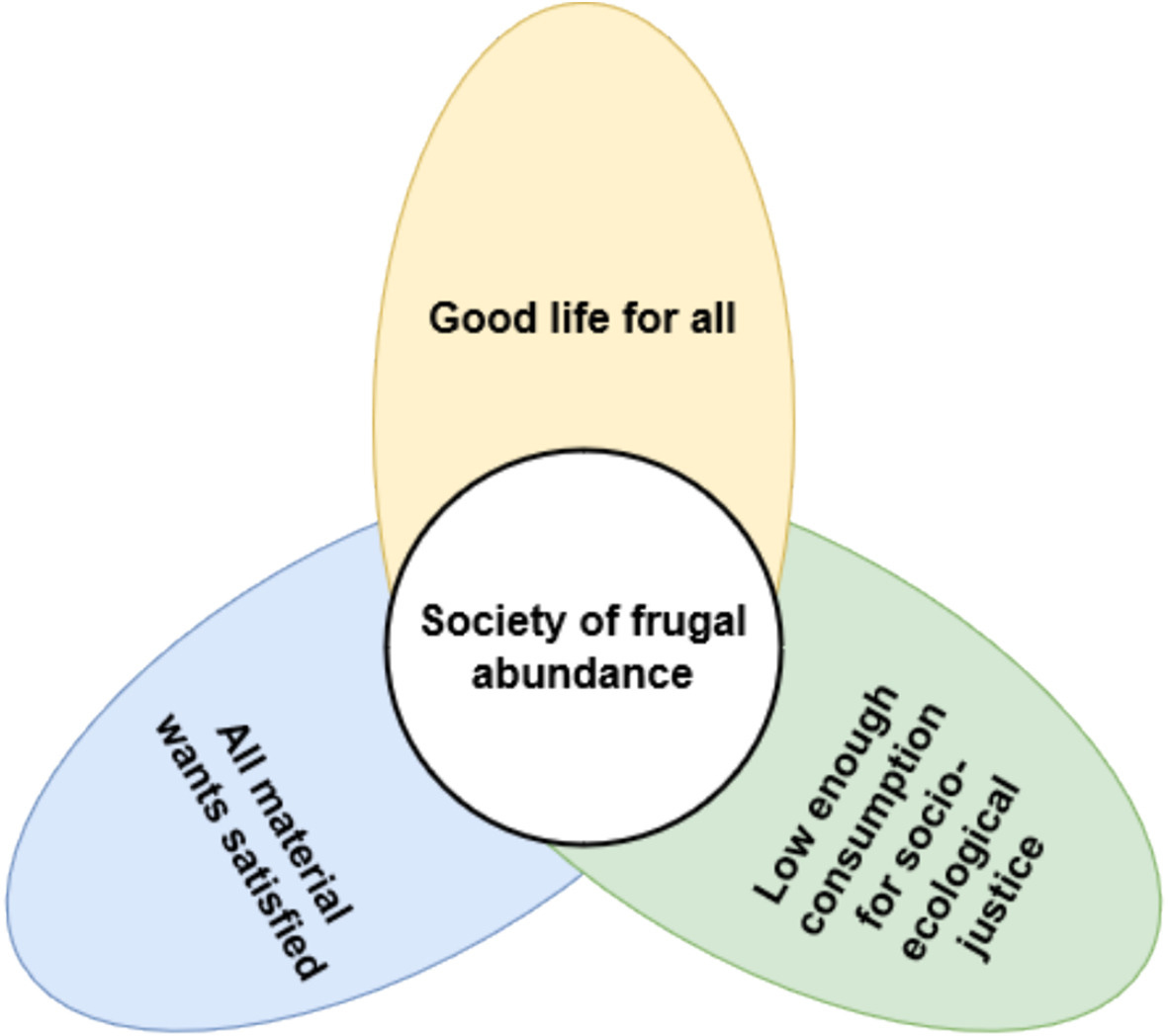

One option is to think more about the concept of frugal abundance. In a society where everyone has a good life, consumption is low enough to achieve global ecological and social justice, and everyone's material wants are satisfied, this is where obesity could decline. Also, from this research, it is clear that materially wealthy people do not tend to be more happy than (materially) poorer people.

As we all know from our personal lives, proper growth lies in finding balance. Living a healthy, fulfilling life requires us to be mindful of having enough rather than constantly seeking more. This means recognizing when we have eaten sufficient instead of overindulging and appreciating what we have instead of wanting it all. We strive for balance through adequate sleep, physical exercise, meaningful social relationships, and fulfilling work. This is the essence of a good life.

If we understand this as individuals, we can apply it to society.

He who knows that enough is enough will always have enough.

(Lao Tzu)

Obesity and growth

Obesity is a growing global health concern that has significant implications for economic growth. The relationship between obesity and economic growth is multifaceted, involving direct and indirect effects on productivity, healthcare costs, and overall economic stability. I won’t go into all of it. Of course, you can imagine that obesity leads to higher healthcare costs,1 productivity losses (see here), and disability and earlier retirements (see here). If these factors dominate, high-obese societies should perform worse than low-obese societies. Effectively, these factors lead to societies that spend more time and money on negative side-effects than on creating well-being.

I want to concentrate more on the effects of material wellbeing that lead to higher obesity:

Income Levels and Food Choices: As economies grow and incomes rise, dietary patterns often shift towards higher-calorie, processed foods. This phenomenon, the nutrition transition, can contribute to rising obesity rates (see here). Increased disposable income may also lead to more sedentary lifestyles, exacerbating obesity.

Urbanization and Lifestyle Changes: Economic growth often leads to urbanization, which can reduce physical activity levels. Urban areas may offer fewer opportunities for physical exercise and increased access to unhealthy food options, contributing to higher obesity rates.

Healthcare Access and Preventive Measures: On the positive side, economic growth can improve access to healthcare and preventive measures, potentially mitigating some of the adverse health effects of obesity. Investments in public health campaigns, nutrition education, and physical activity programs can help address obesity at the population level (see here).

A study (2019) dives into this question by analyzing 40 years of data from 147 countries. The key takeaways:

Higher Income, Higher Obesity: The study found that as a country's income increases, so does its obesity rate. This trend slows down but remains positive even at higher income levels.

Globalization's Role: Countries more integrated into global political systems see a stronger link between income and obesity. This is likely due to increased access to processed foods and changing dietary habits.

Urbanization and Agriculture: Surprisingly, urbanization and a larger share of agriculture in the GDP tend to weaken the income-obesity link. Urban areas might offer better access to healthy food options and exercise facilities, while agricultural economies might have lower processed food consumption.

Future Predictions: Obesity is expected to rise, especially in low- and middle-income countries, with an average annual growth rate of 2.47% from 2019 to 2024.

This study highlights the urgent need for targeted health policies to manage obesity as countries grow wealthier. If we don't act, the rising tide of obesity could pose significant health challenges worldwide.

It is not the only study. This article highlights that economic growth is the underlying probable systemic driver for childhood obesity in South Africa. Some studies show the existence of an Obesity Kuznets Curve (obesity first rises with income and later declines), such as this one. Results seem to depend on samples, period and focus (individual versus macro data). This theoretical paper shows that outcomes might differ dramatically, depending on the trade-off between consumption and exercise (again, it is simply the first law of entropy…).

Returning to my own experience, I can understand the existence of an Obesity Kuznets Curve. I am an example of it. However, this might be the case within countries, while we only see a rising (expanding) trend between countries.

Frugal Abundance is the answer to obesity

In the face of global ecological and social crises, "frugal abundance" has emerged as a pivotal framework within the degrowth movement. This idea challenges the traditional notions of wealth and consumption, proposing a radical shift towards a society where abundance is achieved through frugality rather than excess.

Imagine a society where everyone enjoys a good quality of life without constantly consuming more stuff. That’s frugal abundance in a nutshell. It’s not about being poor or denying yourself pleasures but about finding joy and satisfaction with fewer resources. This idea comes (of course) from the degrowth movement, which advocates reducing our consumption to live within the planet’s ecological limits.

This concept ties into the topic here—obesity. In our modern world, obesity is often linked to overconsumption, not just of food but also of resources. We’re bombarded with advertisements pushing us to buy and consume more, leading to unhealthy lifestyles and unsustainable habits.

Frugal abundance flips this script. We can improve our health and well-being by focusing on what we truly need and valuing quality over quantity. Instead of indulging in fast food and endless snacks, we can savour nutritious meals that nourish our bodies and the planet.

Practical Steps to Embrace Frugal Abundance (from article)

Simplify Your Life: Cut down on unnecessary purchases. Do you need that extra gadget or the latest fashion trend?

Eat Mindfully: Choose whole, nutritious foods over processed options. It’s better for your waistline and the planet.

Value Experiences Over Things: Spend time with loved ones, enjoy nature, and engage in activities that bring genuine joy.

Support Local Economies: Buy from local farmers and artisans. This reduces your carbon footprint and supports community resilience.

By adopting the principles of frugal abundance, we can tackle issues like obesity and environmental degradation simultaneously. It’s about finding a balance where our needs are met without compromising our planet's or ourselves's health.

So, let’s embrace this fresh perspective. Living with less doesn’t mean less happiness—it can lead to a more prosperous, more fulfilling life where we all thrive within our means.

And, by the way, losing weight makes any balancing act easier.

That’s all.

Take care,

Hans