#16 Forget wishful thinking; it is about realism and hope

...and graffiti

I've had a rather delightful week on the island of Terschelling, preparing for the Springtij sustainability forum. I am now in Berlin after delivering a presentation for Triodos Bank Germany.

As my late grandmother used to say, "One moment you're here, the next you're there."

Being in vastly different environments can profoundly affect one’s mind (certainly mine). I've been reflecting deeply on whether I've been overly pessimistic about environmental issues or on possibilities for sudden changes, especially considering the tendency to dismiss those discussing degrowth or talking about ecosystem crises as too gloomy. When you are in Berlin, especially at the weekend when Iran attacks Israel, and you walk in the DDR museum, you realise history was never a straight line.

But I also realise that, although it is never a straight line, pressure builds in every system, and then it comes to an outburst. And during that pressure building, those in power tend to do wishful thinking. Look at the history of Germany. Until the last day, the leaders of the Communist Party clung to their seats, wishfully (or wistfully?), thinking that the demonstrations would fade.

The conclusion of my reflection: I think I am not excessively pessimistic. I think there is a lot of wishful thinking. A recent article in the American Economic Review, which highlights how people often succumb to wishful thinking, supports this. I have solid reasons to maintain my belief that we should radically change our economic system to have a future for humanity. Moreover, after reviewing the UN's report on financing for Sustainable Development, one would need considerable wishful thinking to remain optimistic about achieving the Sustainable Development Goals by 2050.

During my travels, I've become increasingly observant of my environment, paying closer attention to the presence or absence of features ranging from the natural landscapes of Terschelling to the street art in Berlin.

For example, we had an enlightening presentation with a representative from Staatsbosbeheer about efforts to restore the dunes to their original condition and achieve better ecological balance. This process involves extensive manual labour to return the area to a more sandy state. Instead of merely discussing nature-based solutions and their financing, this was hands-on work. It also brought me face-to-face with a harsh reality: nature restoration seldom presents a viable business case. Improving ecological balance is labour-intensive, with the sole reward being a healthier environment. No wishful thinking, simply hard work.

While in Berlin, aside from the museums and historical sites, my economist's curiosity was piqued by other aspects of the city. We stayed in a charming apartment in Kreuzberg. However, as you wander around Kreuzberg (or almost anywhere in Berlin), you're struck by a pervasive local hobby which, while irritating to some, adds a unique character to the area: graffiti and street art, including the murals on the East side gallery. The entrance to our building was completely covered in it. Notably, some murals are sanctioned (or even commissioned by the government), and it's fascinating to observe that successful graffiti artists can carve out lucrative careers as mainstream artists, much like Banksy.

In economic terms, graffiti exhibits positive externalities, such as offering free art to the public, and negative externalities, including the potential to spoil views and be seen as vandalism.

Policymakers have struggled to effectively remove graffiti, for instance, by painting over it. However, removing the visible signs of graffiti is an end-of-pipe solution, similar to carbon capture and storage technologies. This approach does not tackle the underlying causes.

My brief exploration of the academic literature on graffiti and street art (surprisingly extensive) highlights that addressing the root causes is crucial.1 Proactive measures such as thoughtful urban design (ensuring fewer appealing, blank walls in low-footfall areas, greening walls), designated graffiti areas, community murals, and public art workshops are more effective than reactive measures. Social policies (community building, social housing, etc.) that help reduce criminality and unemployment can also be beneficial. It's clear there is a fine line between graffiti and street art; what some view as simple vandalism, others may see as art.

We have solutions to the problems at hand at Terschelling and Berlin. However, these solutions are not implemented on the necessary scale, mainly due to priorities and wishful thinking. Wishful thinking that problems will go away if we keep doing what we have always done.

But why doesn't 'change' scale up? Why does it take so long to achieve more sustainable behaviour? The answer isn't economic; it's psychological and social. When faced with the prospect of change, we exhibit a confirmation bias for our current behaviours and experience loss aversion. Adjusting our habits and adopting new, more sustainable practices is challenging.

Good news is seen as confirmation that we don’t have to change our behaviours and that anything can be done. This leads to complacency. The bad news is ignored. The bad news about our ecology is that if we are on track to meet climate goals, people do cherry-picking. We should not be pessimistic, is the mantra.

However, what I want to highlight this week is (1) if we look at all the evidence, we can not be optimistic about progress on climate, on SDGs on ecosystem preservation, and (2) that loss aversion, wishful thinking and confirmation bias stand in the way to get to breakthroughs.

A transition is not about needing more technological innovation. We need social innovation to bring us to a social tipping point and improve our collective behaviour. We need to be anxious sometimes. Otherwise, we don’t see the necessity of changing.

A scary read

Some people might see it as just ‘one of the reports’. And probably it is. However, this Financing for Sustainable Development Report shows so clearly that only extreme wishful thinkers believe the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development is within reach. Or, to be clear: All countries are off track on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, with around half of the 140 Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets for which sufficient data is available, deviating from the required path.

On a “business-as-usual” pathway, where social, economic and technological trends do not shift markedly from historical patterns, the SDGs would remain out of reach even in 2050.

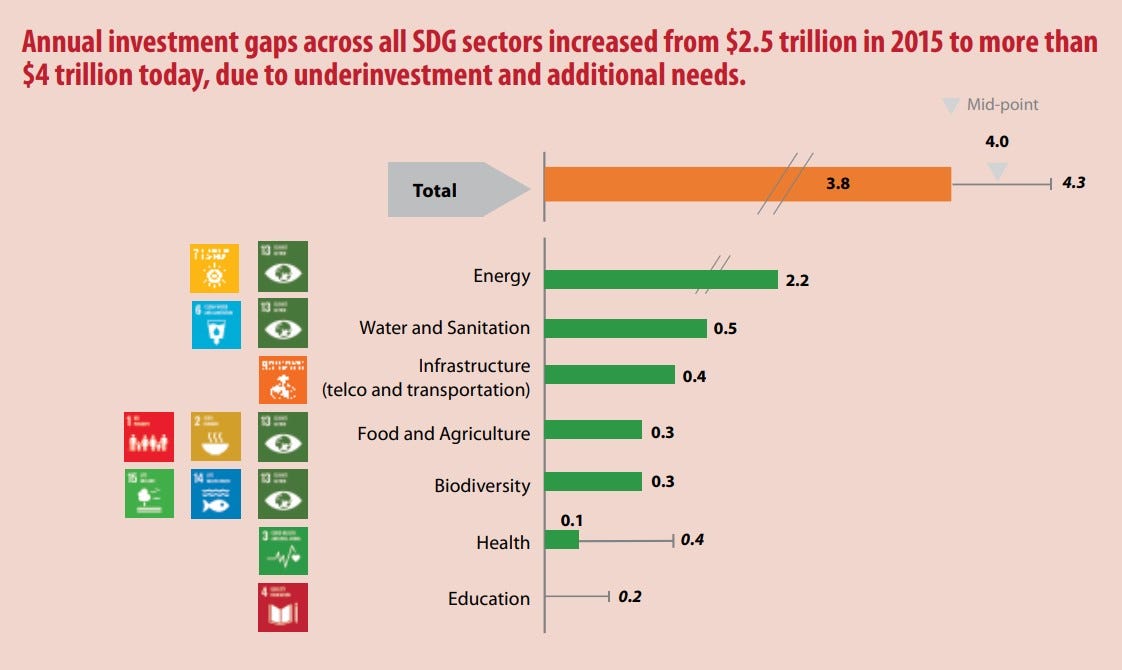

The report concerns financing them and reveals a critical funding gap of USD 4 trillion annually. Before COVID, it was estimated to be USD 2.5 trillion, primarily affecting developing nations.

I have always had doubts about how to calculate a ‘gap’. It is a combination of capital allocated to destruction (fossil fuel subsidies and investments, deforestation, industrial agriculture investments and subsidies such as in the eurozone), risk-return mismatches (private capital that ‘requires’ a higher risk-adjusted return than can be expected from certain investments) and expected investments in mitigation, restoration and adaptation that are extremely hard to quantify. All that said, we need to reallocate capital.

As high as these financing gap estimates are, they pale compared to the costs of inaction. The cumulative economic and social costs incurred from climate change under a business-as-usual scenario through 2050 are estimated to be almost five times larger than the climate finance needed to limit temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Every dollar invested in risk reduction and prevention can save up to 15 dollars in post-disaster recovery efforts.

Unfortunately, that is not how the financial sector sees it. If these risks are too big, they will (definitely!) be socialised. Hence, it does not give any incentive to redirect capital flows.

A not-so-hopegiving quote from the summary:

A number of global trends and developments have significantly reshaped global development prospects and the development financing landscape. These include the rise in systemic risks, above all climate and disaster-related risks; a sea-change in global macroeconomic and macro-financial conditions; dramatic changes in the international division of labour and the pace of global economic integration; rising and entrenched income, wealth, gender and other forms of inequality; enormous technological change, with digitalization in particular affecting all financing areas; and growing risks of fragmentation in the global economy. Some trends have also created tremendous opportunities for development and financing progress. But in their totality, they have put national financing frameworks and the international financial architecture under severe stress.

Source: UN, 2024, p. 3

The steeper financing costs (due to higher interest rates) makes it harder for the most vulnerable countries to finance their needs.

In the meantime, private finance is seen (in the report) as a pivotal player. However, it must align more closely with sustainable development goals to make an impact. The largest part of sustainable finance is nothing else than risk mitigation, as is also in the report (see figure).

There is NO WAY I can envisage where private finance alone could bridge the funding gap using tools like green bonds and social impact investing without some risk-taking by public entities. Public-private partnerships, of course, have the potential to mobilize significant resources by combining the agility of private-sector innovation with the robust support of public entities. However, this can also lead to increased moral hazard, where private gains are made in the name of sustainability, yet the public shoulders risks and losses.

In my view, the only viable solution is a reform of the financial system, as suggested in the report, which would bolster the capability of financial institutions to support sustainable projects through enhanced regulatory frameworks. This report contributes to the discussions leading to the 2025 International Conference on Financing for Development in Spain.

Hopefully, this conference will yield productive outcomes, although I remain cautious, suspecting that much of it may be wishful thinking.

But this is not the only wishful thinking I encounter. In the discussion on degrowth, people always refer to the absolute decoupling of carbon emissions from resource use, which is happening for some countries but not fast enough. As I explained a few weeks ago, it takes a lot of wishful thinking to reduce carbon emissions as fast as needed. A broader view of the energy transition (for instance, in this dashboard) shows that we are off track for most of the indicators. This holds not only for climate but also for resources, as explained before. The problem with many publications is that researchers want to tell a hopeful story because it should not sound too negative. That is when you get wishful thinking.

Wishful biases

We have known for a long time that people have a confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is the tendency of people to pay close attention to information that confirms their belief and ignore information that contradicts it. If you are optimistic (you believe) that innovation can help us solve the climate crisis, you search for confirming evidence. This can take extreme forms:

Many common beliefs appear to be held for their comforting properties rather than their realism. Billions of adherents of the major religions believe in an afterlife, without concrete proof for its existence. Moreover, religiosity is higher in populations that face unpredictable shocks like earthquakes, during pandemics, and in the absence of alternative forms of insurance. People at risk of serious diseases avoid medical testing and remain optimistic about their health status, while greater exposure to COVID-19 leads people to become more sanguine about the probability of infection. Populist politicians who promise easy fixes find more support in areas with weak economic prospects and declining growth rates.

(source: Engelmann et al, 2024, cited without references in text)

Hence, wishful thinking is a bias that can lead to underestimating risks, overly optimistic about things we believe in or value, and complacency.

Engelmann et al.'s article empirically explores how anxiety about adverse events like potential shocks or financial losses can lead people to engage in wishful thinking. They found that when facing potential adverse outcomes, individuals tend to display overly optimistic beliefs, reducing their ability to recognize warning patterns accurately. This behaviour was particularly evident when the signals were ambiguous or the situation complex. The findings highlight how negative emotions influence decision-making, suggesting that people might ignore reality in stressful situations in favour of more comforting, albeit inaccurate, perceptions.

From their conclusion:

They help explain why people seek solace in religious beliefs, why financial professionals ignore red flags about their asset portfolio, why people most at risk of a disease sometimes avoid testing for it, and why voters who are concerned about their jobs and the future of their children are susceptible to reassuring but false political narratives.

(source: Engelmann et al, 2024,p. 956

Be careful with optimism.

It might be contradictory to what people think, but we should be careful with (too much) optimism and too much wishful thinking. We should not (always) blame doom and gloom. According to this thoughtful article, painting a realistic picture might be more helpful. It makes five points:

Action Through Awareness: Contrary to some beliefs, negative or realistic portrayals of environmental crises often spur people into action. An acute awareness of impending ecological disasters has fueled movements like Extinction Rebellion.

Complacency from Optimism: Overly optimistic messages (wishful thinking!) might lead to complacency, making people less likely to take the necessary, often complex steps to address environmental challenges. Realistic portrayals help maintain awareness of the urgency needed for substantial changes.

Oversimplification issues: The dichotomy between 'success' narratives and 'doom and gloom' oversimplifies the complexity of human motivation and response. How messages are crafted and communicated is crucial in their impact, necessitating a balanced approach that includes hope and realism.

Infantilizing Effect: Claiming that people only respond to positive news treats them as mere information consumers rather than as engaged, capable actors in democracy. Research shows that people often underestimate others’ willingness to take action based on critical narratives.

'Moodsplaining' and Honesty: Dismissing gloomy outlooks as merely unhelpful 'moodsplaining' can undermine genuine emotional responses and discussions needed for societal change. Honesty in communications fosters genuine engagement and problem-solving.

This nuanced discussion underscores an evolving recognition that hope and fear can act as catalysts for action and that communication must honour the audience's intelligence and capacity for engagement.

Conveying messages effectively is by no means straightforward. At times, I believe we absolutely must adopt a positive narrative. However, it is crucial not to oversimplify or assume that 'everything will be alright.' In a world beset by multiple crises, such optimism is unfounded.

We should always illustrate what can be achieved, outline a vision for the future, and critique the prevailing paradigm. This approach must be adaptable to different groups and in various formats and always remain constructive, scientifically grounded, and respectful of others.

But never wishful thinking. That leads to complacency. Or graffiti.

That’s all for this week.

Take care.

Hans

Remarkably, no one has come up with the economists’ favourite: Pricing externalities through more tax on graffiti spray cans probably because there are more paint users, so you can not discriminate.

Hans, as you say we are nowhere on track to reach the Paris climate goals. Isn't it time for a change of tack? What is your take on a carbon takeback obligation? I think it might be the backstop policy we need to actually reach netzero (on time) and get the fossil fuel industry on board with the energy transition.

As always, your articles are clear, and consistent. They assume that human cognition and rationality might win out against animal instincts and universal 'laws' of nature, such as: https://www.issuesofsustainability.org/helpndoc-content/MaximumPowerPrinciple.html

(longer version in Wikipedia)

It is the main way one can remain optimistic about reversing the negative environmental trends science affirms daily. I also note, as I wrote in an earlier comment to your blog, that like any species that quadruples its numbers in the lifespan of living individuals, we are in plague phase. This multiplies impacts, and further affects the economics of the shrinking p/capita 'pie' of natural wealth which provides our sustenance and that of most other life forms. It would be great if you could address scale of the feet making ecological footprints on the planet!