#15 Reductionism and efficiency as perfect defending lines

...to do nothing about existential problems

Raising children is a journey of trial and error. My kids, aged 12 and 15, can take on numerous responsibilities, yet it's essential to remember—that they're still children. Whether it involves adhering to bedtime routines, managing homework, handling money, or fulfilling commitments like sports or family visits, I'd like to believe they'd act in their best rational self-interest. Despite the warnings and the "I told you so" moments, reality often unfolds differently.

Indeed, the correct approach to supporting them varies significantly between the two. For my son, clarity is paramount; he anticipates this from me. He explores how far he can extend boundaries, as any child would. Conversely, with my daughter, the strategy diverges entirely. It involves enticing her to undertake more or varied activities; she is inherently disciplined.

Over time, the craft of rearing your children evolves. Everyone can identify with this sentiment—if not as a parent through reflections on your upbringing or perhaps your experiences with pets. It entails adapting to circumstances, setting a proper example, discussing future aspirations (educational pursuits or career choices), transitioning from caregiving to educating, exercising firmness when necessary, and providing comfort and affection at other times. The goal, however, remains unequivocal: to nurture your offspring into responsible, self-sufficient adults. As a parent, you undertake whatever is necessary, navigating through with the finest intentions.

Contrast this with economists, who have many excuses for eschewing responsibility. "This falls outside my remit," "It's not included in the model," or "The empirical evidence deems it irrelevant" are common refrains. They might argue that "this policy lacks efficiency; hence, we should abstain from implementing it."

Economists and policymakers frequently find ample justification to dismiss specific proposals and topics, invoking their 'duty' as a reductive means to avoid grappling with more intricate queries. If you use reductionism too often, you can not see that you do extractive things: caring for a flower and making it grow while not caring for the rest of the environment makes no sense.

The most significant issue is the formation of assumptions about the real world and then taking refuge behind them, as if economics were a natural science governed by immutable 'laws'. And when these laws fail to hold, they are often conveniently overlooked. Imagine applying that approach to parenting.

Why all this? Because last week, I participated in a debate on climate change and monetary policy. To my astonishment (or perhaps dismay), many attendees (all thoughtful, highly educated, and well-intentioned individuals) questioned the central bank's responsibility concerning climate issues. All my arguments were laid out: it's beyond our mandate, lacks efficiency, and is subjective. I was stunned.

Why? Because there appears to be a profound discord between what we humans ought to do and what I was listening to. The simply mind-boggling shifts in temperature serve as yet another alert that ecological devastation is not a far-off dystopian nightmare. Furthermore, this article again underlines that the 'age of destruction' is entrenched in our economic frameworks, making it challenging for these structures to rectify the issue.

Is nurturing an economy (or caring for it) not akin to raising children? Thus, the purpose of a central bank cannot be narrowly defined by reference to its tools. If we face existential threats to humanity, such as ecological collapse, even with an objective like price stability, shouldn't it necessarily be expanded to address this existential threat? What value does price stability hold if there's no economy?

The presenter asked the question, facing this problem, what kind of models, analysis, or vision for 2100 we should need to guide central banks and avoid collapse.

I did not answer that day; the discussion still astonished me.

But the short version of my answer is a few points:

Forget reductionism; embrace complexity

Be clear about (economic and hence monetary) objectives and be aware of the underlying values

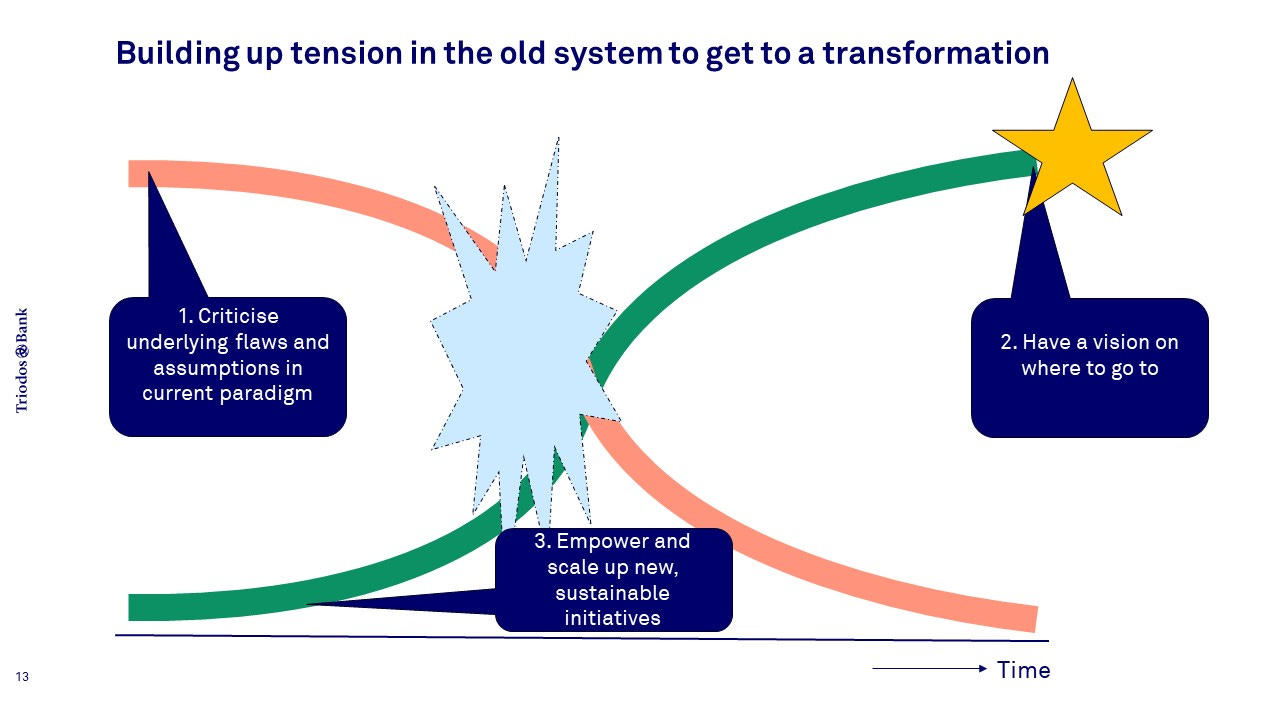

Handle sustainability transitions with love and care: give room for new initiatives, criticise what is wrong with current paradigms and have a vision of where you want to go. Transition management implies for economists that it is about more than efficiency.

Ultimately, it is not about new models for me but about better assumptions. It is about very carefully examining the current logic of economics and finance. Then, we can conclude that the underlying values (monetary and financial) do not include humankind's objective: survival. Complex, systemic risks cannot solved by reductionism. That is the problem. The rest is a distraction. So, to make it personal, if I succeed in raising my children in the best possible way, what does it mean if I don’t take responsibility for the earth's future generations to live upon?

I don’t apologize for making it lengthy. There is always so much more to say... Maybe next week, when I am in Berlin, I won’t have much time to write.

Earth at risk

Last week, I discussed the polycrisis we are experiencing based on a recent article. This week, a newly published article is (again) raising the alarm about our ecosystems and the system itself. You could argue that I tend to select and read the most alarming articles. I think that is not the case. We have every reason to be alarmed if we look at ecosystems. The only claim you can make against me is that I always look for articles linking different societal elements: ecological, social and economic. It is complex, but then you always see that we have a problem that is not an isolated hobby of some ecologists but an existential crisis as the root cause of our economic and financial system.

The beginning of this article is alarming. Climate-related mass extinction of 14-32% of plant and animal species can happen even under intermediate climate change scenarios, while 600 mln people live outside the human climate ‘niche’. To highlight only the prospect of children, children born today will experience 7.5 times as many heatwaves, 3.6 times as many droughts, three times as many crop failures, 2.8 times as many river floods, and two times as many wildfires as children born in 1960.

The authors also highlight that, despite the climate pledges and the Paris Climate Agreement, the world economy is completely off track on reducing carbon emissions. to stay within 1.5 degrees, we have a carbon budget for six years if we keep on emitting the same amount.

This is doom and gloom but also reality. The more interesting question is what drives it and how to eliminate it.

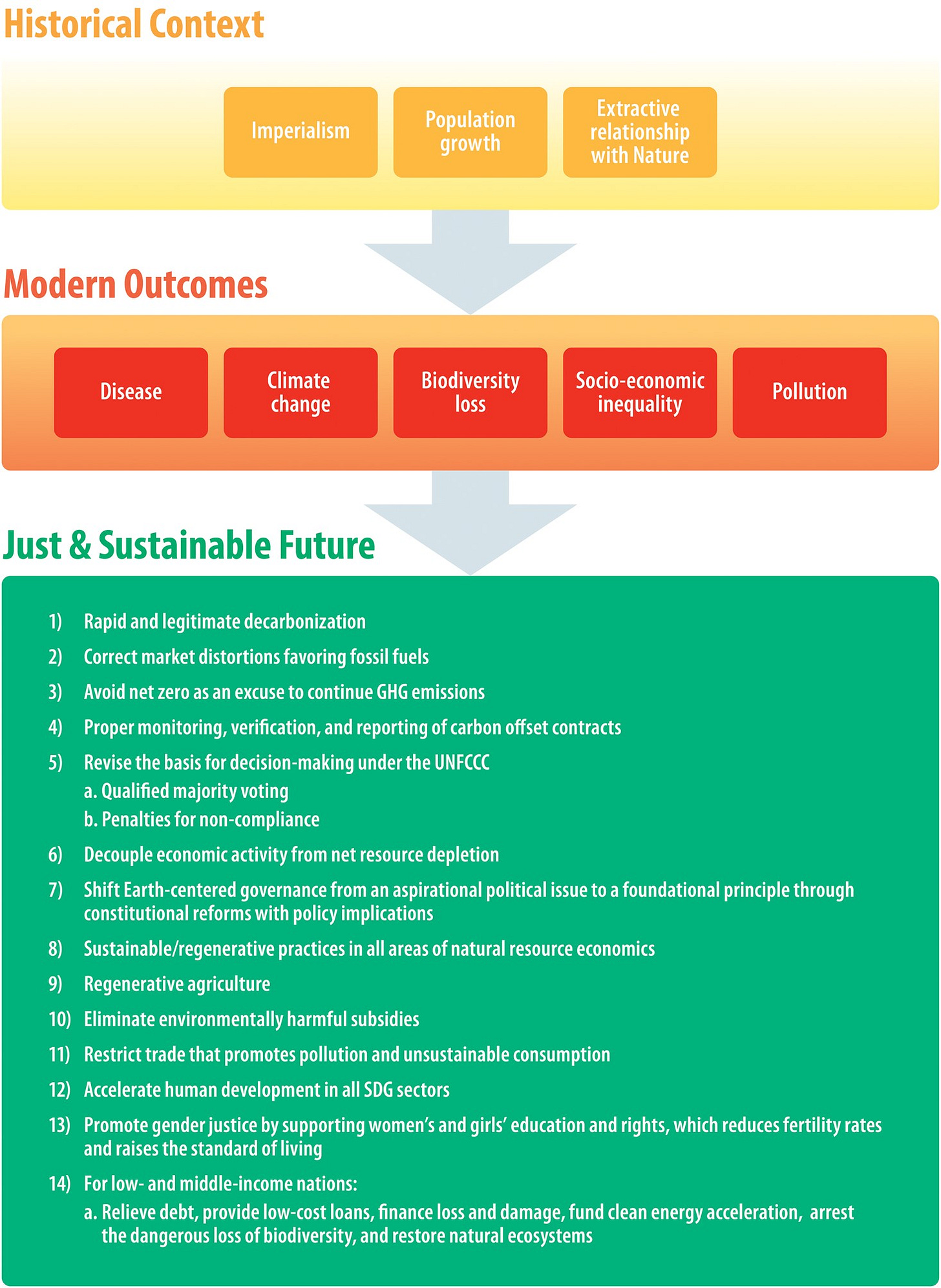

In this article, they conclude that the drivers are population growth, an extractive relationship with nature, and imperialism (see figure).

Industrial capitalism, which places a premium on resource extraction and profit maximisation, epitomises modern imperialism. This approach is intricately woven into the fabric of international relations, shaping trade agreements, political dynamics, and the economic policies of nations, including their monetary strategies. The enduring dependency on extractive economic models poses a formidable barrier to achieving essential progress in areas such as decarbonisation, the conservation of natural resources, and the promotion of social equity.

The challenges posed by industrial capitalism are further exacerbated by global population growth. The world's population will rise by nearly 2 billion over the next 30 years, reaching approximately 10.4 billion by the mid-2080s. According to Dasgupta, this figure far exceeds the Earth's optimal population capacity, estimated to be between 0.5 and 5 billion. This discrepancy suggests that the planet is already surpassing its ecological carrying capacity.

The expansion of the human population invariably disrupts or destroys wild habitats through urban development, agricultural expansion, and increased resource consumption. Consequently, humanity's demand on the biosphere surpasses what it can sustainably support, highlighting the urgent need to reevaluate our economic models and growth strategies.

The authors claim that the change needed is much more than what has been done in recent years.

They claim that:

It is past time to build a new era of reciprocity with nature that redefines natural resource economics. The ecological contributions of Indigenous Peoples through their governance institutions and practices are gaining recognition and interest. Indigenous systems of land management encompass a holistic approach that values sacred, ethical, and reciprocal relationships with nature, integrating traditional knowledge and stewardship principles to sustainably manage land and water resources. Indigenous land management challenges conventional power structures and introduces innovative solutions to environmental issues, especially in the context of climate change.

Indigenous Peoples exercise traditional rights over a quarter of Earth's surface, overlapping with a third of intact forests and intersecting about 40% of all terrestrial protected areas and ecologically intact landscapes. […] We suggest that an Indigenous worldview, that of kinship with nature, should define sustainable practices.

(source: Fletcher et al. 2024)

To do that, they propose a list of changes that should happen (see figure), most of which are already known (so I will not elaborate on this here). You could even say this is mainstream policy with many buzzwords (decoupling, correct distortions, monitoring, regenerative agriculture), so why is this new?

However, it is. They end with a section about…values, which brings me back to those economists and their discussion.

Values, objectives

Their list of what should change in terms of a cultural shift in values consists of 11 points (shortened it a little):

Education in sustainability and equity concepts: Embedding sustainability and equity into educational curricula at all levels can shape future generations’ values and actions.

Policy, legal frameworks, and legislation: Governments can enact and enforce policies that mandate sustainable practices and ensure social equity.

Economic incentives: Shifting the economic focus from growth at any cost to a model that values environmental and social well-being.

Cross-sector partnerships

Community empowerment and inclusion

Corporate responsibility and accountability

Incentives for sustainable/equitable behavior: Channeling investment into developing and deploying green technologies that enable sustainable production and consumption patterns. Creating economic and social incentives for businesses and individuals to adopt sustainable practices, like subsidies for renewable energy or tax benefits for sustainable/equitable business practices.

Innovation and technology

Leadership and commitment

Cultural narratives: Leveraging media, art, and culture to promote stories and images that valorize sustainability and equity, thereby shaping public opinion and cultural values and changing the cultural narratives around consumption and progress to value sustainability and long-term thinking over immediate gratification or economic growth at any cost.

Global engagement and solidarity: Participating in international efforts and agreements that collectively address global challenges and ensuring sustainability and social equity are global priorities.

I think not all are about values; some points are simply executing policies.

To bring it back to the discussion in the beginning, two things are crucial here: clarity about objectives and embracing complexity, hence also responsibility.

To start with, the first one is obvious. Let me reiterate a figure I used a few weeks ago. If the biggest challenge is the collapse of our ecosystem, there should be no discussion on the ranking of objectives: first, the ecosystem, then the economy. This implies (automatically) that the criterion to judge an action (policy) should be aligned with that objective. Hence, reductionist economic reasoning (for instance, price stability) should be broadened and judged upon the broader consequences of the overall aim.

Let’s give an example of monetary policy to clarify. If price stability is the primary objective (as it is), it should always be judged against the (complex, overarching) aim of getting an economy within planetary boundaries. This does not have to be in the mandate but in the values (if we get the cultural shift right). The current narrative is that price stability can be achieved through changing interest rates (sometimes accompanied with quantitative easing or tightening). The idea is quite reductionary. In case of high inflation, raising interest rates should lead to a higher cost of capital, leading to less investments, lower asset prices, more saving and less borrowing. This, in turn, should slow down economic activity, resulting in unemployment and, in the end, lower inflation. Central bankers believe firmly in this story, although evidence of the last few years about the success of these policies (both tightening and easing) is mixed.1

However, if it (also) leads to higher capital costs, especially for renewables, it hinders price stability if the price surge comes from fossils. There is much central banks can do about greening monetary policy; see here or here.

In the long run, there is also no other option than considering ecological considerations: what is the use of price stability when there is no economy?

However, the honest discussion is about the underlying values. Many claim that ‘conventional’ monetary policy is objective (non-normative). It is not. It is subjective in the sense that price stability is the primary goal, and all consequences are justified: distributional effects such as unemployment, wealth destruction, or creation are seen as ‘side effects’.

In general, every choice is subjective. A choice to judge monetary policy only by price stability, to judge the health of an economy by gross domestic product, and to judge the success of a company based on the profit it makes is all subject. Just because it is possible to reduce a measure to a monetary value does not imply that it is objective. It is reductionist and leads to judging policies based on the wrong metric.

Transitions, with love and care

What is the way forward, then? It is not a new model but a better or more detailed vision for the future. It is about understanding the failures of the current paradigm, empowering new thinking and new initiatives and setting the right objectives that align with that future vision.

This is transition management. There is a whole literature about it and even a research institute about it. I am not going to explain everything here about how you get change, the difference between niches, regimes, and landscapes, and everything related to getting change done.

I want to limit myself to the three ways you need to build tension in the system to reach a transition.

First, it is about criticising the flaws and underlying assumptions in the current paradigm. “In the absence of unambiguous foundational truth in the social sciences, the only sensible way forward can be conscious pluralism”, as Pettigrew stated (2001, p. S62). Constructing different theoretical and conceptual models helps to distinguish ideas that can be generalised further from those that depend on specific assumptions. A research finding, principle, or process is judged to be robust when it appears invariant (or in common) across at least two (and preferably more) independent contexts, models, or theories. Those findings will eventually be selected in an evolutionary process. However, this process is not without problems. If the established theory based on this selection process becomes a paradigm, it is hard to falsify it. At least part of the economics community sees economics as a positive science, close to physics. As Friedman stated:

“…positive economics is, or can be, an "objective" science, in precisely the same sense as any of the physical sciences.” (Friedman, p.4)

Viewed in this light, it emerges as a research paradigm. However, the nature of paradigms is such that, despite being refuted on multiple occasions, proponents often defend their position by critiquing other research for its data quality, underlying assumptions, and methodology while overlooking the shortcomings within their paradigm. Consequently, for many scholars and practitioners, these become seen as a 'set of immutable truths' rather than a collection of falsifiable knowledge. This results in the 'stickiness' of research and its estrangement from reality.

This phenomenon was something I witnessed once more last week.

Secondly, the focus shifts to scaling up new ideas, initiatives, and actionable solutions. Academia is rife with fresh and innovative ideas. Regarding economic structuring, there exists a spectrum of market-based economies, each with its unique ownership and governance frameworks. Generally, facilitating transitions effectively involves making space for diverse ideas. However, this notion starkly contrasts with the prevailing economic models where scale dominates nearly every industry, including finance, fostering monocultures and leaving little room for diversity.

Thirdly, formulating a vision for the future seems to be a more straightforward task. Envisioning an inclusive society that operates within planetary boundaries is not particularly challenging. The more pressing issue is figuring out how to achieve this vision.

This is where the parenting analogy becomes relevant: You may have a vision or an idea of what your children might become as adults. However, the journey towards that vision is essentially a process of navigating uncertainty.

In the news

New research found that the EU has made polluting diets “artificially cheap” by pumping four times more money into farming animals than growing plants. No wonder farmers are protesting. They have a lot to lose.

A new report by InfluenceMap about carbon majors underscores a stark reality: a small cluster of major emitters is significantly responsible for the lion's share of global CO2 emissions since the Paris Agreement, and they're not showing signs of slowing down production. These 57 corporate and state entities alone can be tied to 80% of fossil fuel and cement CO2 emissions from 2016 to 2022.

When we delve deeper, the figures paint a concerning picture: nation-state producers contribute 38% of emissions in the database post-Paris Agreement, while state-owned entities and investor-owned companies account for 37% and 25%, respectively.More scientific evidence affirms the effectiveness of climate action:

A German study shows that climate protests effectively elevate concerns about climate change, particularly in regions with low awareness levels. No significant evidence supports the notion that aggressive demonstrations hurt climate change concerns. The disruptive nature of climate protests underscores society's reliance on activists and amplifies their constructive objectives.

A US paper gives more insights into what kinds of nonviolent civil disobedience (NVCD) works and what does not. Reactions to NVCD are more positive when the target and action are perceived as appropriate. Soup-throwing and targeting museums were viewed unfavourably, possibly leading to criticism. NVCD aims to disrupt daily life and raise awareness, but broad support from diverse demographics is crucial for meaningful change in democratic societies.

That’s all for this week.

Take care.

Hans

I am not going into all the details here, but both the period after the financial crisis (when we had a large-scale monetary loosening experiment) and the recent monetary tightening as a response to the energy-price-induced surge of inflation resulted in inflation and the success of the policies are mixed. Even when inflation is coming down (as is happening now), it is not clear that it can be attributed to monetary policy (because the prominent channel of unemployment did not work in most countries). Also, it can not be concluded that it did not work, simply because we don’t know the counterfactual. Much more to say, much more literature to refer to, but not now.

Hans, can you select the front you use at Substack? In gmail it is not so readable so I tend to revert to the linkedin update version..

“the 'age of destruction' is entrenched in our economic frameworks,”

The “age of destruction” can also be described as the transition strategy of Growth through Creative Destruction.

This transition strategy that monopolizes our common sense today is the special pleading for the special interests of professionals expert in the capital markets, which depend on volatility and growth in share prices to deliver liquidity that market participants demand as a condition of their participation, a condition that market professionals must honor if the want to make money making markets for shares. Which they do.

The more liquidity in the markets, the more fees and profits for market professionals.

Growth in share prices comes ultimately from increases in transaction volume, measured in prices paid in money from one period of measurement to the next, without any consideration of the nature of those transactions, or their consequences.

Instead we are assured that more will always be better. Axiomatically.

So the formula for a good economy is Growth in GDP to drive Growth in NPV to drive Growth in NAV to drive Growth in AUM to drive Growth in fees and profits for market professionals which, we are promised (without evidence and in defiance of lived experience) will always be better for everyone.

Underneath simple numerical growth in transaction volumes, however, are qualitative changes in the circumstances and possibilities for doing the work of learning about ourselves and the world about us, and putting that learning into action through enterprise and technology to offer choices to everyday people for living our best lives under the circumstances by using technology to solve the everyday problems of everyday living everyday: the flourish and fade of popular choice from among competing technologies as times change and humanity evolves prosperous adaptations to life’s constant changes.

In the capital markets this flourish and fade shows up as the boom and bust of Creative Destruction.

In his recently released 2024 Annual Letter, BlackRock CEO Larry Fink, tells us, “in Finance, there are basically two choices”: banks (debt) and the capital markets (equity, and also debt).

If Larry Fink is right, we are doomed to bust our way destructively into a new reality of being human at a planetary scale in the 21st Century, and beyond. The capital markets are in charge, and what way the capital markets finance transition is through Growth and Creative Destruction.

There is nothing central banks can do to change that.

There is nothing governmental policymakers can do about that.

There is something pensions can do.

Pensions can stop financing Growth through Creative Destruction in the Capital Markets, and start financing Prudent Stewardship of the Flourish and Fade of learning and technology in the real, physical commercial economy of enterprise and exchange for sharing an abundance of technology solutions to the everyday problems of everyday people living our best lives under the circumstances as circumstances change, every day, to innovate a safe and dignified house for humanity within built environments of Urban, Rural, Curated and Left-Alone landscapes along the creative edge of a constantly changing Human partnership with Nature, choosing new beginnings from time to time, and over time, as times change, to fit the changing times, shaping the right enterprises for shaping the right technologies for shaping the right choices for shaping the right economy for shaping a cohesive society and keeping it ongoing in shared hope for a dignified future quality of life for all.

There is something central banks can do about that.

There is something governmental policymakers can do about that.

There is something we each can all do about that.

We can convene and contribute to a new globally curated conversation about the purpose of the pension promise, the powers of pension fiduciaries, the possibilities for supplying pension money to enterprise and the accountabilities of pension fiduciaries for supplying money to the right enterprises in the right way to shape the right technologies for shaping the right choices for shaping the right economy for shaping a cohesive society and keeping it ongoing in shared hope for a dignified future quality of life for some, directly, that must also be, of necessity, hope for a dignified future quality of life for us all, consequently.

Because right now, they are not doing that.