#14 The best of times (when you're rich and healthy), but for how long?

Degrowth or green growth: a tale of two utopias?

At times, I contemplate that from my privileged position, holding a comfortable job in a prosperous country (and incidentally, this prosperity in our nation is rooted in a colonial past and sustained by natural gas exploitation over recent decades—why else would one become so affluent dwelling in a marshy region?), it's perhaps the best era to be alive.

The Netherlands is experiencing warmer temperatures on average than before. Unlike many of my fellow Dutch citizens, I don't particularly enjoy ice skating in the winter, so the milder weather is more comfortable for me (apart from the rain). Additionally, the disappearance of many bothersome insects (such as those found on the windscreen of cars or mosquitoes at night) is a welcome change. However, despite our ability to live as we please and not be restricted from refraining from clearly damaging behaviour, it's difficult to deny that we currently enjoy favourable conditions. And we all know that this, ultimately, poses a threat to humanity. It's a comfortable yet concerning situation—a kind of comfortable polycrisis. And because it's so comfy, who would want to change it?

That is where we are. And that is why the debate about radical change and transformations gets more intense. For instance, I see a lot of degrowth debunking, as there was already much green growth debunking (there is much more on this).

Debunking both ideas, or almost any radical idea about the future, is relatively straightforward. They're founded on scattered empirical observations and experiments within our current non-sustainable economic framework and projected into the future. Both demand substantial human feats: creating the necessary technologies to avert disaster or fostering mindset shifts that enable contentment with less. Essentially, they're both utopian.

So, uncertainty is significant for both. Where should we place our bets, then?

For those with a lot to lose, it is tempting to bet on innovation. The reason has nothing to do with the likelihood of success. The choice is based on the fact that if you bet on innovation, you don’t have to change anything now.

However, a new article this week clearly shows that it is unlikely that we will achieve decoupling.

My conclusion: scientifically, the likelihood of achieving an economy that operates within planetary boundaries is exceedingly slim. Furthermore, I increasingly recognise that this isn't the most crucial narrative. The paramount tale is to envision that future anew. Let's not lose ourselves in the struggle; instead, unite to reimagine societal transformations. Let's embark on this journey before the best of times turns into the worst of times.

"It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way--in short, the period was so far like the present period that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only."

Source: Charles Dickens (1859), Tale of two Cities

Where we are: A polycrisis

It was in the news this week. The evidence is that our natural habitat is falling apart. In the Netherlands, for example, a study shows that the number of butterflies has halved in the last 30 years. At the same time, the European Union seems unwilling to accept an (already watered down) Nature Restoration Law. What is happening here? I think the correct diagnosis is that we are in a polycrisis (like I said before), but that life is too good in this polycrisis for people who have a lot of (political) power and money. We call these people vested interests.

A new paper on the polycrisis explains why ‘this’ differs from before. They define a global polycrisis as the causal entanglement of crises in multiple global systems in ways that significantly degrade humanity’s prospects. The interconnectedness of various global systems exacerbates the negative impacts, surpassing the cumulative harm that would have arisen if the host systems were not profoundly entangled. Consequently, the confluence of these interacting crises significantly and irreversibly affects the economy and the financial system in unanticipated ways.

In the paper, I saw the same systemic risk globe I have been taking to presentations for 1.5 years.

They explain (better than I did) the core implication of this systemic risk idea:

Intra-systemic impact: A disruption that affects one part or area of a single system quickly spreads to disturb the entire system (via multiple, ramifying chains of cause and effect, or some form of contagion, through the system's causal network).

Inter-systemic impact: The disruption of the initial system may spill outside that system's boundaries to disrupt other systems.

They added two things to previous studies of polycrisis: the vectors and conduits of global polycrisis and the properties of the worldwide system that enables them.

The first (vectors) are more or less by what means (energy, matter, information and biota) parts of the system are affected. Through today’s planet-spanning web of connections are the conduits through which these vectors travel worldwide.

As the authors argue, what is different from (recent) history is (1) that the world is far more interconnected (hyperconnected) now than it was during the, for instance, the 1970s economic crisis, and (2) the world economy is more homogenised, i.e. through the pursuit of efficiency as a main evaluation criterion for economic activity and open access to markets while stripping away social and environmental safeguards there is less resilience of the system. In other words, we created a system more prone to polycrisis.

Another point the authors make is that the properties of the global system enable a polycrisis. The name things like multiple causes, non-linearity, hysteresis, boundary permeability and black swan outcomes are all related to complex systems (also reminded me a little about the work of Gunderson and Holling on Panarchial systems).

I added this to my old slide (👇). It makes it more complex, but that is, at least to me, the message. Don’t concentrate in a reductionist way on the outcomes such as biodiversity loss or overconsumption. Take the system into account.

Turning to our current systems, the authors argue that we see multiple systems in unstable states:

The Earth environmental system is leaving its Holocene equilibrium and entering a period of instability due to anthropogenic perturbation of the climate and other physical and ecological systems (Armstrong McKay et al. 2022; Barnosky et al. 2012; Rockström et al. 2021; Steffen et al, 2018). This instability is already causing enormous human harm, and its effects could become catastrophic in the near future (Kemp et al. 2022; Xu et al,2020).

•The global human energy system has begun to shift away from its dependence on fossil fuels. Whether this shift will culminate in a new zero-carbon energy equilibrium is uncertain: technological bottlenecks and incumbent opposition may block its progress. The shift's economic benefits are also uncertain: it could ultimately force humanity to decrease its energy consumption per capita (Hall, 2018; Smil, 2022).

•The international security system is changing from a world order based on American leadership (a ‘pax Americana’) toward an uncertain and likely less-stable multipolar order defined by the rise of China and the diffusion of power to a much wider range of actors (Gilpin, 2002; Ikenberry, 2014; Nye, 2011). Historically, such transitions have been accompanied more often than not by major war (Allison, 2017; Gilpin,1988).

•The global economic system is shifting from a neoliberal economic regime – one undermining itself through worsening instability, inequality, and ecospheric externalities – to a yet indeterminate regime, but one likely involving increased dirigisme and economic integration within ideological blocs (Birdsall and Fukuyama, 2011; Monbiot, 2016; Rodrik, 2011; Rodrik, 2019).

•The information system is being revolutionized by artificial intelligence, with unclear but likely unprecedented implications for employment, decision making, and personal, national, and global security.

Standard economic and policy analysis does not provide an answer to this. It is complexity science, interdisciplinary science, and a holistic policy agenda. Or, as the authors concluded, Focus on crisis interactions, not isolated crises—address system architecture, not just events. Exploit high-leverage intervention points.

In other words, it is a radical transformation, not just shallow solutions.

The fallacy of fantasies

We are talking about radical transformations. It is difficult to grasp, but not so difficult to show what the difference is between pure fantasies and possible Utopias. A new article by Jackson, Hickel and Kallis discusses (again) the possibility of decoupling economic growth from carbon emissions. They react to this article, where the first bullet reads: “The pessimist assumptions on decoupling by some degrowth scholars presuppose an economic collapse of unseen magnitude”. That is (non-)Academic framing!

Essentially, it is all about the old-school IPAT relationship for impact:

I= P x A x T

The impact (I) is the pressure on ecosystems, P is population growth, A is affluence (wealth), and T is technology. In these articles, PXA is used together (as in Gross Domestic Product), so the discussion concentrates on how carbon emission reduction (I, limited to carbon, c) can be achieved with or without growth. If T improves (or carbon intensity per euro declines) GDP growth can be decoupled from its impact on climate change.

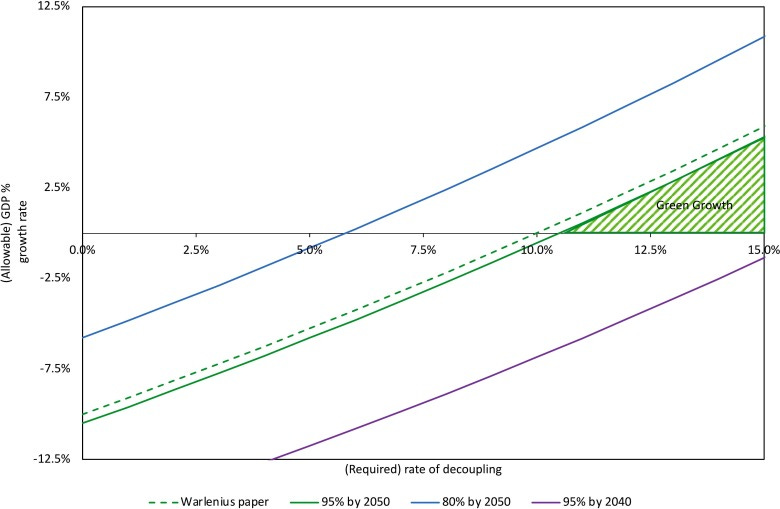

Only reduced to those two variables, it is not so difficult to show the relationship (see figure below).

This figure can be interpreted in two related ways. On the one hand, for each line (representing each carbon target) on the graph and for any given rate of decoupling (shown on the x-axis), the y-value along the line indicates the maximum allowable annual growth rate necessary to achieve that specific target. On the other hand, for any anticipated growth rate shown on the y-axis, the x-value along each line indicates the annual decoupling rate required for that target to be met. In essence, the lines represent a form of climate reduction isoquants.

This analysis shows that meeting the Paris Agreement (aiming for a 95% carbon reduction by 2050) necessitates a minimum annual decoupling rate of at least 10.5% if the economy is not allowed to shrink. Green growth is possible, but very unlikely.

While we observe some instances of (absolute) decoupling in various countries, it is not occurring globally and at the required rates.

Another argument still getting much attention is that we need growth to pay for the energy transition. So, decoupling should go faster if we can invest more in it. There is simply no evidence for it. Jackson et al. also give some arguments, mostly saying that if you keep prioritising growth, it will probably also lead to promoting every growth-enhancing activity, cannibalizing people and the planet further (because it remains about holy profits).

Furthermore, we will need not only decoupling from carbon emissions (carbon tunnel vision remains a stubborn beast). The challenge is decoupling all impacts of our economic system on ecology. For instance, for resource use, decoupling is probably much harder.

To return to my beginning, if we, as a society, want to achieve our sustainability goals, we should do everything we can, although there is no proof for it. Investing in technologies to accelerate decoupling is a good idea. But a utopia should not be a fallacy. Therefore, we have to discuss the demand side of the economy and how we can take steps to reduce growth dependencies.

But all this and innovation will require more than we have ever seen—again, a radical transformation. And not because it will be easy. But because it is necessary.

Imaginations for transformations

What we need to get there is probably not more academics that claim to have the truth, not more models, equations or conceptual discussions. We also don’t need businesses, the winners of the old system, proposing how the future should look like. We also don’t need (populist) politicians to claim that they know what the world looks like, who is the scapegoat and give voters a false sense of security that there is something like ‘going back to the good old times’. In times of a polycrisis, we know one thing for sure: there is no way back; there is only one (uncertain) way ahead.

And what can help then is imagination. Imagination for radical transformation. This paper that I came across gives nine dimensions for evaluating how art and creative practice stimulate societal transformations and how to engage with deep leverage points.

They created a 9 Dimensions tool, or different ways to talk about creative practice and chance (see figure) along three categories, each covering three dimensions: changing meanings (embodying, learning, imagining); changing connections (caring, organizing, inspiring), and changing power (co-creating, empowering, subverting).

All these dimensions can, in one way or another, help in sustainability transformations. In general, all these dimensions help to either open up to different thinking and avoid carbon tunnel visions (changing meanings), make other connections with people or ideas that unlock new inspiration and collaboration (changing connection), or set people in different roles and assignments together, altering (implicit) power (in)balances to come to new results.

There is much more to it. But in general, creative processes can help to change current positions, whether given in by interests, conviction or ignorance. There is only one way to find out if it works: by having creative interventions on a larger scale.

In the news

Why don’t humans respond to extinction-level risks? Human civilization faces many critical extinction-level threats, such as climate change, biodiversity loss, nuclear war, pollution, and AI risks. The reasoning in the article (which I agree mainly with):

- People don't oversee the complexity of our civilisation and, if they do, cannot act individually.

- Systemic issues like climate change require large-scale changes in infrastructure and industry beyond what individual actions can achieve.

- The current economic system is driven by profit maximisation. It incentivizes behaviours contributing to risks (e.g., if pollution is free and pumping up fossil fuels is highly profitable) while discouraging mitigation efforts (because they are a cost).

- Despite the urgency of these threats, people tend to perceive them as distant or someone else's problem, hindering collective action.

- Technology is often seen as a solution, but it's also recognized as a significant contributor to many risks.

- Despite human resilience, survival is uncertain in the face of catastrophic events.Despite the evident adverse effects, many responsible investors continue to pour funds into fast fashion. The Financial Times questions this phenomenon, pointing out the contradiction in supporting companies driving low-quality clothing consumption

Oil and gas companies are way off-track from Paris Agreement goals: Climate alignment assessments reveal oil & gas company transition risk examines the 25 largest listed oil and gas companies and evaluates the extent to which they are aligned with Paris-climate goals.

That’s all for this week.

Take care.

Hans

In order to define something as a "crisis" we also need to define what is the expected normal we're comparing it to...

Our inherent inability to understand complex systems and our need to control our surroundings makes us see as crisis any variation from what we believe to be normal or makes us uncomfortable...

But some might say that our need to intervene naively in systems we don't really understand is the exact reason we end up with crisis and black swan events.. because by removing the volatility from a complex system we are practically stopping it from finding a new balance.. this results in accumulated internal forces and increases the risk of a more violent breakdown when a truly unexpected event occurs..

Sometimes inaction is far better than naive intervention..

Just a different thought..