Why limits to wealth are more urgent than ever

A system failure that is difficult to discuss

Yesterday (29/11/2023) Ingrid Robeyns presented the Dutch version of her public book on Limitarianism. It is a book intended for a wide-ranging audience, in which the author argues for the importance of discussing our moral, ecological, and political concerns regarding certain individuals who belong to the super-wealthy class.

I was pleased to receive the first (official) copy from Ingrid.

The theory of Limitarianism diverges significantly from theories concerning optimal wealth distribution or efficient markets. It commences with the perspective that moral constraints exist on an individual's wealth accumulation and their appropriation of various other types of scarce and valuable resources.

A few arguments favour an absolute (or relative) limit to wealth (see also here for the academic version). The first one is unmet urgent needs: as long as people at the bottom of the wealth distribution have needs that can not be satisfied, there is an imperative to redistribute from rich to poor. Of course, this also relates to studying minimum thresholds in society (because, if all needs are met, why should you redistribute)? However, with increasing wealth at the top and absolute and relative poverty in almost every country, this is only a theoretical counterargument. Robeyns argues that this unmet-needs argument leads to absolute maximum wealth, estimated between 1 and 3 million euros in the Netherlands. However, as Ingrid highlights in the book, this perspective varies from country to country, contingent upon factors such as public provisions and the pension system. Another argument posited is the democratic standpoint, asserting that excessively wealthy individuals translate their abundance into political influence, thereby manipulating regulations to the detriment of others' well-being. A third consideration is ecological. Given the link between wealth and resource utilization, particularly in scarce resources and ecological degradation, limiting wealth could be seen as a measure of fairness to curtail resource consumption.

There are many things to say about limits to wealth, but let me limit (😀) myself to the points I made yesterday (a few weeks ago, we also did a podcast).

The key points include exploring why the discourse surrounding extreme wealth has evolved and become more pressing than in previous times. Additionally, there is an emphasis on the necessity to counteract the potential trivialization of arguments from mainstream policymakers and economists. The role of the financial sector is also underscored as a crucial leverage point in addressing extreme wealth.

(1) The discussion on limits is time and place-dependent

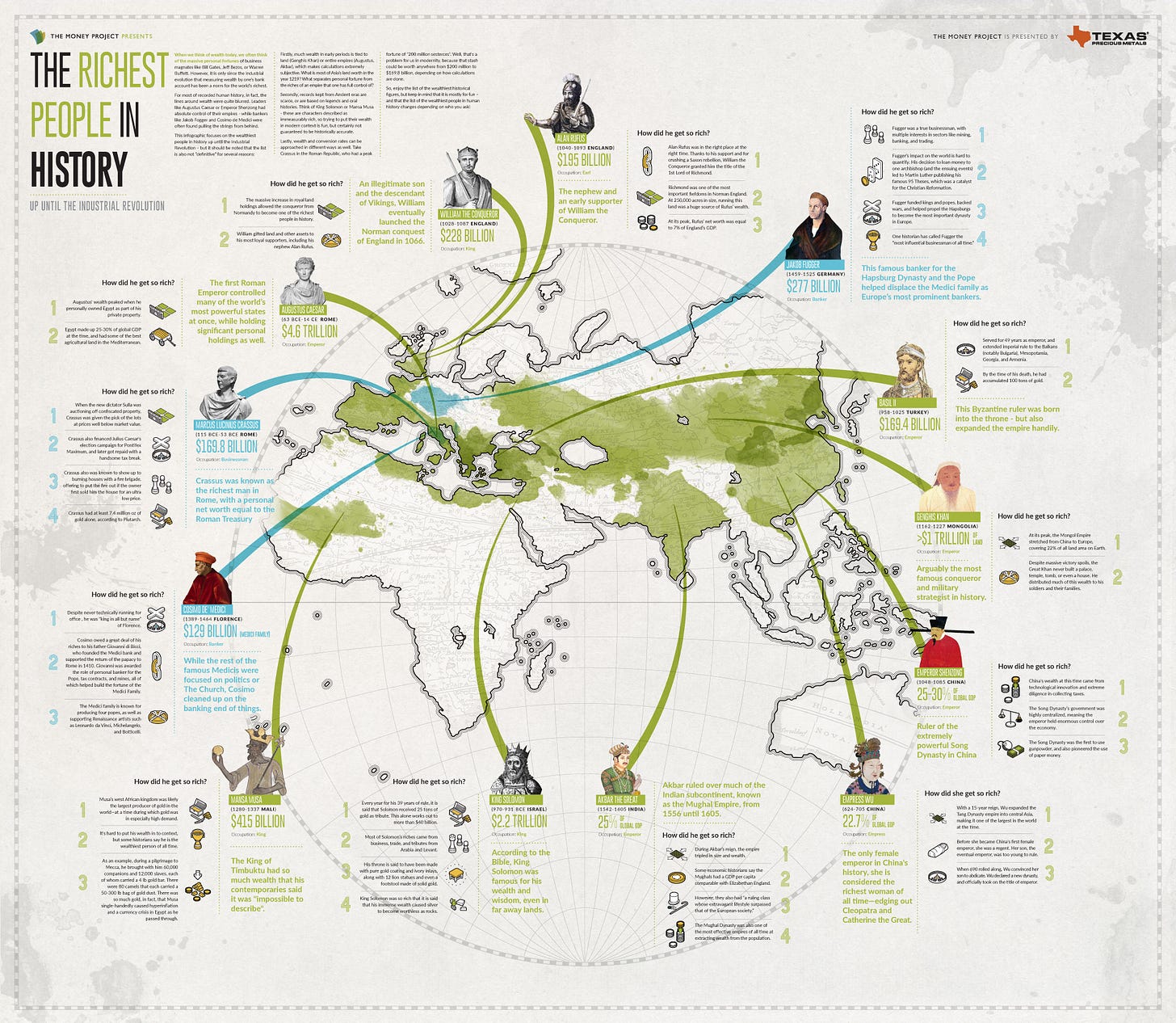

Of course, you can argue that there have always been extremely wealthy people. For a part, it has brought us nice things like pyramids, art and innovations (sometimes also the source of their wealth). However, it is now a little different

Infographic: The Richest People in History (visualcapitalist.com)

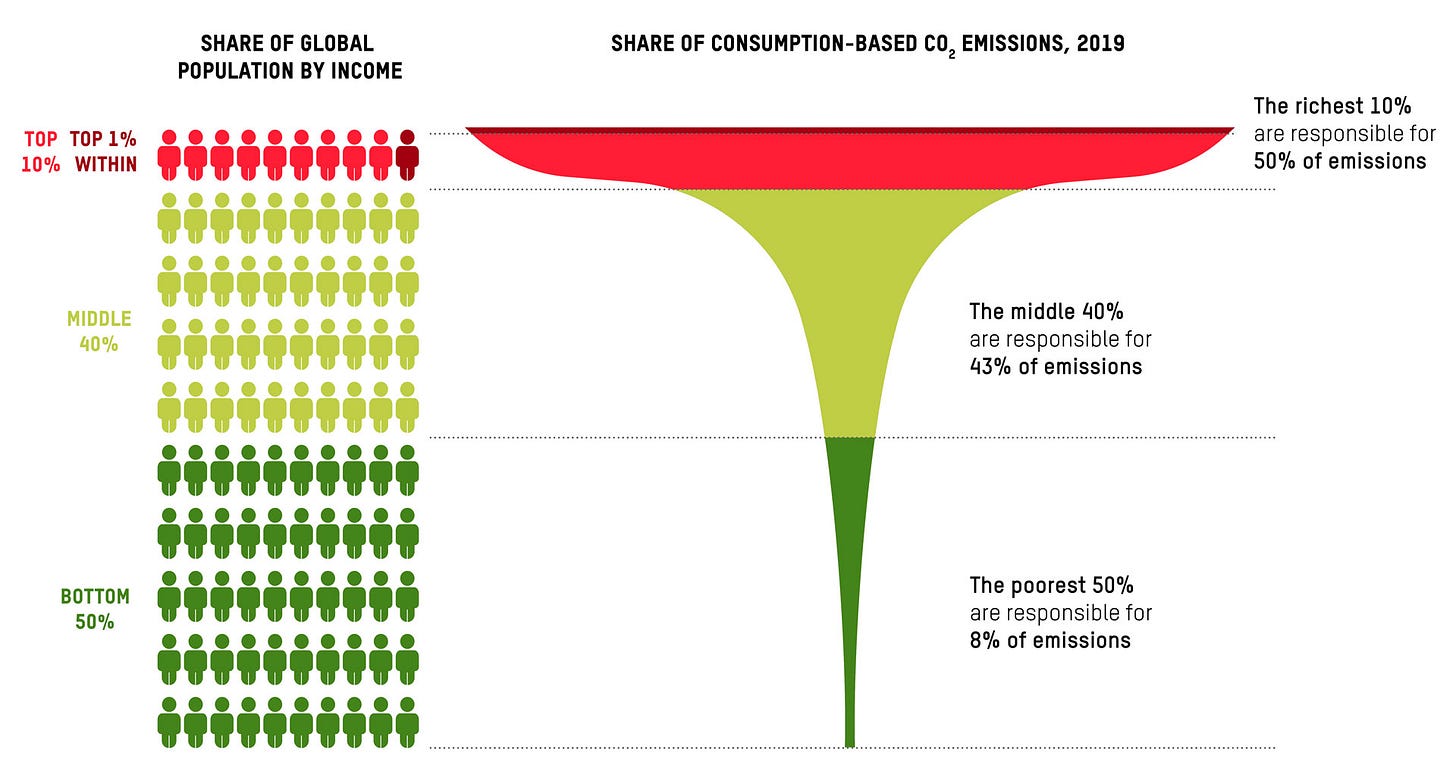

The ecological crisis we are in can not be decoupled from distributional aspects. The wealthiest 1% contributes more carbon emissions than the poorest 66%, according to an Oxfam report from last week.

From the Oxfam report:

“The super-rich have a taste for burning carbon excessively – be it in their private jets, superyachts, mansions or spaceships. One study examining the consumption emissions of 20 billionaires found that each produced an average of over 8,000 tonnes of CO2 a year. The major causes are their yachts and jets. A superyacht alone, kept on permanent standby, generates around 7,000 tonnes of CO2 a year. There is a clear story here about the intersection of social, gender and economic inequalities. Private jet owners are overwhelmingly white, older (over 55) men who work in banking, finance and real estate. The overconsumption of the super-rich also makes luxury goods and activities that fuel excessive carbon emissions desirable and aspirational to the wider population. This plays a significant role in driving superfluous consumption in the rich 10% and desires in the middle 40%, putting the future of people and the planet at even greater risk.152 It also disincentivizes the many from changing their own lifestyle choices. Why should they make sacrifices when the super-rich have free reign to live a luxury, carbon-intensive life”

Therefore, amidst this climate crisis, we must engage in discussions regarding what we consider an acceptable level of wealth for individuals and its subsequent contribution to the climate crisis.

Furthermore, the origins of wealth today differ significantly from historical practices. In times gone by (refer to the infographic above), wealth acquisition often involved conquering land, suppressing populations, engaging in slavery, and resource extraction. Nevertheless, with contemporary wealth no longer inherently tied to physical control over resources, particularly since the Industrial Revolution, affluent individuals are less compelled to care for the communities from which they derive their wealth.

Nonetheless, in the present day, the origins of wealth have undergone a shift. While wealth may still have ties to tangible economic activities in some instances, it is increasingly associated with more anonymous practices, such as relocating production to low-wage countries. Importantly, once wealth is amassed, the methods employed to expand it become entirely detached from genuine economic activities. This is also the asset manager capitalism: the (concentrated) asset manager industry makes the wealthy more wealthy (although the uber-wealthy might probably manage part of their wealth themselves.

The distinction from historical contexts lies in the fact that, rather than confronting the consequences of one's extraction and degradation, the current scenario obscures the visibility of actions and their impact in specific locations.

(2) We should popularise the arguments instead of trivialise them

My biggest worry in the coming days/weeks is that Ingrid's arguments in her books will be ridiculed in the debate. There are two ways to do this. The first one is to concentrate on the exact number. Should it be 1 million euros, 10 million, whatever. And then discuss that it is not feasible, that this is only envy et cetera. The exact number is not what matters, it is about the debate of what we, as society think is acceptable. But the debate is partly hindered by the fact that most of us, or at least a majority, is hindered by neoliberal upbringing: we have forgotten that wealth and ownership is only a societal convention and not a natural law.

The second way of trivialising the argument is by economists saying that it is not economically efficient. See here (in Dutch) already one of those reactions. Indeed, if one were to consider economic efficiency arguments solely, the assessment would likely be against an absolute maximum, citing potential welfare losses, tax evasion, reduced innovation, and so forth. However, this isn't the primary argument nor the sole relevant criterion. The objective is to deliberate on a limit rather than mandating it through legislation. While one approach involves taxing wealth beyond a designated threshold, the discussion (and policy proposals) can also initiate from a redistributive standpoint—questioning, for example, the rationale behind an individual owning a company and reaping all associated benefits.

Moreover, the criteria for evaluating such proposals extend beyond economic efficiency alone. Externalities, such as carbon emissions, should certainly be encompassed within the efficiency criterion, but ethical considerations and their impact on political institutions should carry substantial weight. Although challenging for some economists, these ethical dimensions are undeniably relevant and warrant careful consideration.

(3) The financial sector is enabler of extreme wealth

Lastly, consider the role of the financial sector. While I've previously mentioned asset manager capitalism as a factor contributing to the detachment of extremely wealthy individuals from the consequences of their affluence, there's more to explore.

The financial sector amplifies inequality: affluent individuals receive superior service, benefit from expert advice, can optimise their portfolios more effectively, and financial advisors assist in 'tax optimisation'. Historical trends demonstrate that the wealthy can outperform the average economic growth—a variation of Piketty's r>g, specifically applicable to millionaires and billionaires.

This, of course, aligns with the revenue model of a segment of the financial sector: generating income by aiding wealthy individuals in amassing more wealth. Monetary easing has notably inflated wealth over recent decades. Even during periods of monetary tightening, the wealthiest have proven adept at expanding their fortunes, as indicated by a UBS report predicting continued growth in the coming years.

While the financial sector has the potential to make different choices, such changes run counter to their established revenue model. Consequently, transformative shifts are unlikely to originate within the sector itself. Possible interventions include imposing limits on loans or reducing interest rates on high-wealth savings accounts, among other measures. However, these are inherently ethical considerations rather than purely economic ones.

To conclude: Extreme wealth is one of the system problems we have, that are hard to discuss. So read the book, somewhere next year also in English. Hopefully, it will be the start of a fruitful discussion.