It’s peculiar that sustainability has become a political issue. We saw it in the European elections, where the Green Deal was a significant battleground. We see it in the US, where Trump asks Big Oil to support his campaign with $1 billion in exchange for changing laws in their favour. Crony capitalism to the max. A summary of the debate and the divide between science and policy can be found in this Guardian article.

We see it everywhere in rich countries: sustainability is seen as leftist. I think it is not leftist; it is progressive and running against the vested interests of significant capital: the fossil fuel industry, the industrial agro-complex, and polluting businesses like the fashion industry. But sustainability is in the interest of voters at this moment. It is not about the distant future.

Moreover, it aligns with what most people think should happen. This week's UN report (People’s Climate Vote) has interesting data. Four in five people (80 per cent) globally are calling for their country to strengthen its commitments to climate action, where people are increasingly worried about climate change, especially in countries that experience worse than usual extreme weather. Most people are concerned about the climate and understand that action is necessary. Even more so, in countries heavily dependent on fossil fuel production, a majority also want more substantial climate commitments (see table below). So why is ‘sustainability’ a political wedge issue?

After all, it’s clear that the climate is warming, nature is increasingly under pressure, and a future where this planet remains somewhat enjoyable requires policies to make the world more sustainable.

The problem doesn’t lie with the topic itself but likely (apart from the vested interests) with the policies. Sustainability policies have primarily focused on the end goal of a transition, highlighting what can no longer be done and much less on the immediate benefits. A combination of fear-mongering and inconsistent policies doesn’t present an appealing perspective for taking action. Economists argue that pricing is the best option, leading people to see their energy bills or fuel costs rise, which is hardly appealing. What progress has been made, from renewable energy to the circular economy, has been built alongside the current economy to avoid resistance and sidestep discussions about phasing out old practices.

Health benefits

But how should we proceed in times of polarization? How can we implement policies that people, from right to left, populist to activist, will support? Here are a few simple principles that might help.

First, focus on the short-term benefits. There are plenty of examples to draw from. Climate change increases our exposure to heat stress, allergies, infectious diseases, and pollution. Addressing these issues improves public health. Meat production significantly contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, deforestation, and nitrogen levels. Excessive consumption of processed and red meat poses health risks such as bowel cancer, diabetes, and strokes. Reducing meat intake directly benefits health. Climate policies now will reduce future costs, though that might seem too distant for some.

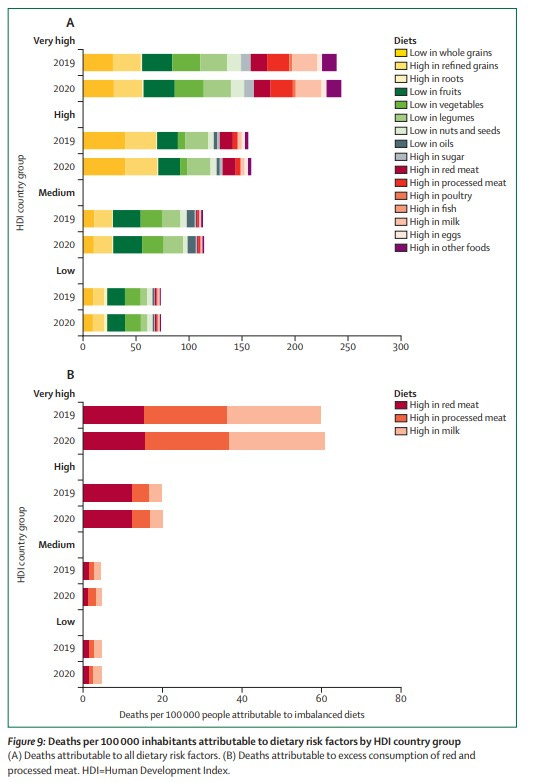

To make this more tangible, take a look at the data and results in The 2023 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change. The report highlights the severe impact of dietary risks on global health, estimating that 12.2 million deaths in 2020 were linked to poor diet choices. This marks an increase of 282,000 deaths compared to 2019. The findings emphasize the importance of adopting balanced, low-emission diets to improve health outcomes and reduce mortality rates.

Of the total deaths, a staggering 7.8 million were due to insufficient consumption of essential foods like fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds. On the other hand, overconsumption of dairy products and red and processed meats played a significant role in health and environmental issues. These dietary habits contributed to 57% of agricultural emissions and were responsible for 1.9 million diet-related deaths, or 16%.

The report also reveals a stark contrast between countries with different levels of human development. Very high Human Development Index (HDI) countries experienced the highest rate of diet-related deaths, 2.4 times higher than low HDI countries. Furthermore, the death rate related to excessive consumption of dairy and red and processed meats in these very high HDI countries was 6.7 times higher than the average mortality rate in other HDI groups.

These findings underscore the urgent need for dietary shifts towards more balanced and environmentally sustainable eating habits to improve public health and reduce environmental impact. Adopting such diets promises significant health benefits and plays a crucial role in combating climate change.

Imagine a world where changing what we eat and how we travel could save millions of lives each year. It sounds almost too good to be true, but recent research suggests that transitioning to healthier, low-carbon diets could prevent up to 12.2 million deaths annually. By simply eating more fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, nuts, and seeds and cutting back on red and processed meats, we can significantly improve our health and reduce our environmental footprint.

But the benefits don't stop at our plates. Shifting to more accessible and sustainable travel options—like walking, cycling, public transport, and electric vehicles—could prevent an additional 460,000 deaths yearly. These changes would reduce harmful PM2.5 emissions from travel, which are tiny particles that can penetrate deep into our lungs and even enter our bloodstream, causing severe health issues. Plus, choosing active travel options like walking and cycling naturally encourages more physical activity, helping us stay fit and healthy.

And there's more good news: these positive changes would ease the burden on our healthcare systems. Healthier diets and greener travel would lower the demand for medical care, reducing healthcare-related emissions. This creates a virtuous cycle where improving our health also benefits the planet.

Cost savings

Second, household cost savings should be emphasized, particularly in the circular economy. A washing machine that lasts twice as long because it’s easier to repair costs much less. Sharing tools with neighbours eliminates the need for everyone to own a drill. Using a shared car is demonstrably cheaper than owning one. While this doesn’t apply to everything, it does for many sustainability measures. The best contribution to financial security is money you don’t have to spend. This could (of course) be countered by saying that making products more sustainable and calculating a price for ‘external effects’ (compensating for pollution, waste, etc.) makes the products more expensive. That is true. But not over a lifetime. And not compared to unsustainable products. The costs to society will come anyway, so prevention is always better (and more cost-effective).

Of course, this is at odds with those businesses and NGOs that advocate circular Economy as a ‘trillion-dollar opportunity’. It should not be. If that were the case, all those gains and cost savings would not be used to save but to spend on other stuff. Rebound effects in practice.

Behavioural change

Third, encourage behavioural change by enticing rather than punishing people (see also the article in this LinkedIn post). Instead of primarily aiming to calculate ‘true prices,’ which makes everything more expensive, we should entice people towards sustainable alternatives. This can be done in various ways. Sometimes, by promoting new technology – electric cars, sustainable phones – likely first embraced by wealthier households. Other times, it can be done by greening neighbourhoods or making rental homes more sustainable. The goal isn’t to convince everyone and get a critical mass on board. A critical mass between 25 and 50% of the population can create a social tipping point, a normative shift where sustainable behaviour becomes the new norm.

Social Tipping Interventions (STIs) offer a promising alternative. STIs aim to create significant behavioural shifts by targeting specific groups and pushing behaviours past a threshold where further adoption becomes self-sustaining.

STIs are inspired by Ecological Tipping Points, which refer to thresholds in natural systems that, when crossed, lead to significant and often irreversible environmental changes. In contrast, social tipping points are designed to leverage these social dynamics, using targeted nudges to destabilize the status quo and promote new, sustainable behaviours.

Generation Break

Fourth, as an extension of this, generational policies should be implemented. By getting young people accustomed to a ‘different’ normal, they won’t suffer from loss aversion later on. So, instead of quickly transitioning to a fat bike, encourage cycling (thus implementing driving licences). Offer driving lessons in electric cars. Promote healthy eating and exercise by making them more affordable.

Vested interests

Does this mean no unpleasant policies should be implemented? Of course not. Abolishing fossil fuel subsidies is challenging but essential to advance the transition. Addressing entrenched interests that highlight the downsides of every sustainability transition is crucial. The longer we wait, the more expensive it gets.

But if a majority of the world’s population wants more climate action and if it is also in their immediate interests, they should resist misinformation, crony capitalism, corruption and bribery.

I believe that favourable, sustainable policies are indeed possible now. They offer many advantages, even in the short term, especially for those who voted for the parties forming this cabinet.

Based on an opinion article in Het Financieele Dagblad (in Dutch)

“Addressing entrenched interests that highlight the downsides of every sustainability transition is crucial.”

Yes, but how?

The problem is money.

Money is the solution.

The problem is money is the solution.

We need to find money with the mission, the duty and the scale to take control of both sides of the transition- the away from and the towards-to mediate the tensions between convention and innovation to rapidly redesign and reconstruct our global energy supply ecosystem to be purpose built for energy sufficiency complete with habitat longevity and social equity on a planetary scale in the 21st Century and beyond

Policy, which means politics and politicians, do not have the scale. Politicians are constrained by national boundaries and national interests as expressed through electoral politics and election cycles.

Pricing, which means Corporations and the Capital Markets, do not have that mission. The corporation is a financing agreement with the Capital Markets for Growth through Creative Destruction to deliver the volatility and growth that the markets need to deliver liquidity and opportunities for profit extraction to market participants.

Transition is not Growth.

Orderly is not volatile.

Destruction is not orderly. Or equitable. Or just.

Neither policy nor price has the duty.

Fiduciary Money has all three.

But Fiduciary Money is captured by the Capital Markets in a narrative that is in fact a sales pitch for the special interests of capital markets professionals in exercising monopoly control of this money, to keep it “focused on increasing profits for Wall Street” (Bernie Sanders)

This is a story of Assets, and Asset Owners, and Asset Allocations across Asset Classes and Asset Manager Selection by Consultants who benchmark them against each other for maximizing purely pecuniary risk-adjusted returns on investment extracted from other market participants.

This is not fiduciary.

It is not sensible.

And yet, it is.

That is wrong.

We need the law to right that wrong.