During the climate summit, it's not about the climate but mainly about money. Money to clean up the mess from emitting countries and to limit the damage, especially in countries that have contributed much less to climate change. Money to accelerate the energy transition and finance climate adaptation. The focus is on the private financial sector because public funds are insufficient.

Despite an increasing influx of private money and the rise of sustainable finance, things aren't taking off. Alarm bells are ringing in reports about the 'financing gap': there needs to be much more money for sustainability than is currently flowing, from both public and private sources.

This study estimates that USD 6.2 trillion of climate finance is required annually between now and 2030, and USD 7.3tn by 2050, to deliver Net Zero – a total of almost USD 200tn (see below).

Where does it go wrong? You would suspect (by defining a gap), that we have to close that gap to have more capital available for those needs. But that is not the case; it is a matter of allocation.

Firstly, governments and the financial sector continue to pump significant amounts into fossil energy. According to the International Monetary Fund, global fossil fuel subsidies were $7 trillion in 2022 or 7.1 per cent of GDP. Explicit subsidies (undercharging for supply costs) have more than doubled since 2020 but are still only 18 per cent of the total subsidy, while nearly 60 per cent is due to undercharging for global warming and local air pollution. It's high time to stop this. This isn't about more money, but less money.

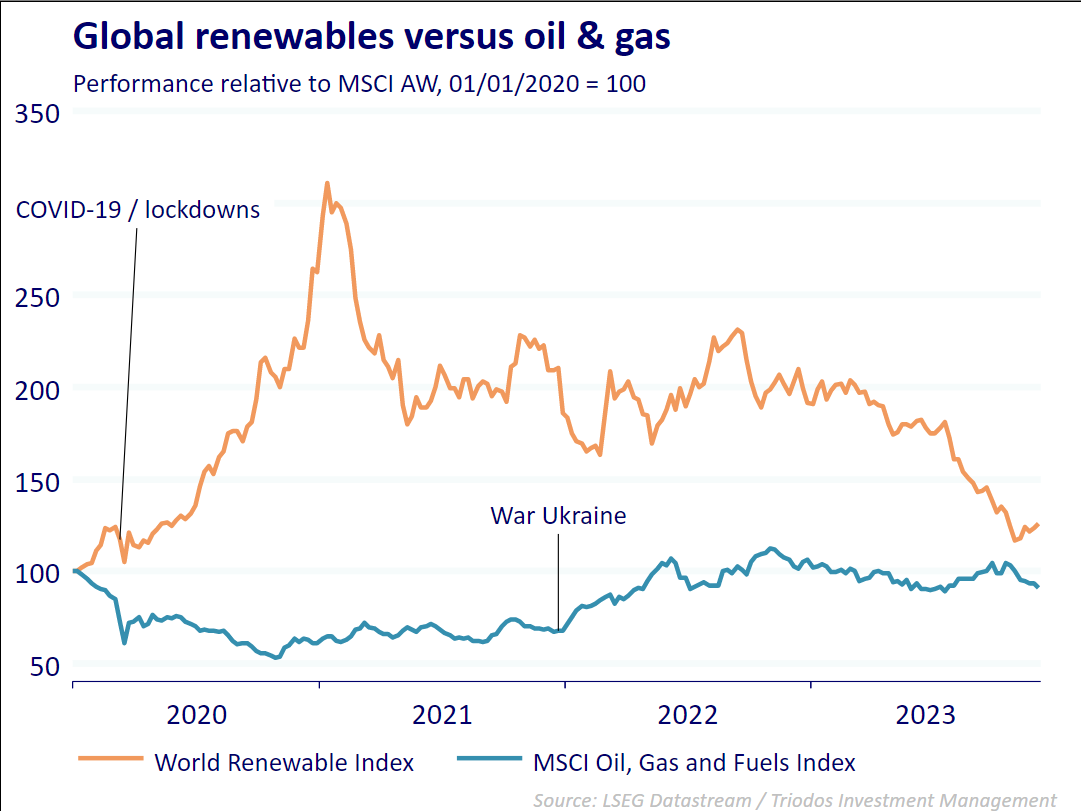

Looking from a distance at the financial sector, you might understand, with a bit of goodwill, why they continue to finance fossil fuels: if shareholders demand profit maximization within legal frameworks, fossil fuels were a good investment in the past year and a half; better than renewables (👇). While the COVID-19 period, with low requests for fossil fuel (less travel, lockdowns) was good for renewables, Ukraine war, the COVID-19 recovery and higher interest rates were bad for renewables and good for fossils. So, if your mandate is driven foremost by short-term return considerations, it is logical to stay fossil.

This is also what happens, as the ECB shows: “Banks talking more about their environmental policies and goals tend to lend more to brown industries.”

So, understandable, but as a sector, don't come with all kinds of promises (such as the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA), of the Glasgow Financial Alliance on Net Zero (GFANZ)) without a real validation for immediate action and spare yourself and us the trip to Dubai.

A second problem is the misconception that there is not enough money. Nonsense, I would say, money is abundant. However, a lack of (private) capital is willing to make climate investments with modest return expectations. Some argue climate financing will become profitable through innovation, scaling, etc. Perhaps, but certainly not quickly enough and not for everything. This is due to the asymmetry of financing. You can make money from something free or (too) cheap, but once the social costs are factored in, it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to make a profit. And since it is private capital that needs financial returns, even factoring in these social costs will not do the trick. Pricing externalities might help a little. But then still, costs for new infrastructure (network capacity and infrastructure) are hard to finance privately. As long as the financial sector is not forced to invest, or the risk is not borne at least partly by others (governments, us), everything remains the same. Stopping financing is not a business model.

So, it's not a matter of too little money. We are subsidizing and financing the wrong things. For now, the financial sector is mostly part of the problem and too little of the solution. Might be better if a lot of those investors and bankers stay at home, and think about the best role they can take.

(abridged version from this article (in Dutch) in Het Financieele Dagblad