Is an energy and resource transition possible with growth?

I doubt it

The challenge in addressing significant problems is ensuring unintended consequences do not arise. Examples of this abound: dams built for hydroelectric power that destroy local ecosystems; antibiotics effective against bacterial infections but leading to bacterial resistance with overuse; pesticides once thriving in pest control and increasing agricultural productivity, now causing diseases and poisoning.

Another common mistake is making very technocratic, ideal-world assumptions in scenarios that show that solutions are possible. For example, infrastructure plans that always cost more in the end. Football fans who think their club or country can win are the ones who get disappointed the most. And, of course, economic scenarios based on the current institutional setup and expecting things that never happened in the past will occur.

In short, we often attempt to solve problems without considering the side effects and make assumptions that help us conclude. This also applies to the energy transition, known as "carbon tunnel vision". We overlook the side effects of pursuing clean energy, such as the rising resource demand, which will pose significant challenges. And also too optimistic assumptions are made in the scenarios of the Global Resource Outlook published last week. And the tragic thing is that even with these too optimistic assumptions, scaling down global resource use is impossible.

Because one thing is missing: discussing reducing economic activity.

Increasing demand for resources

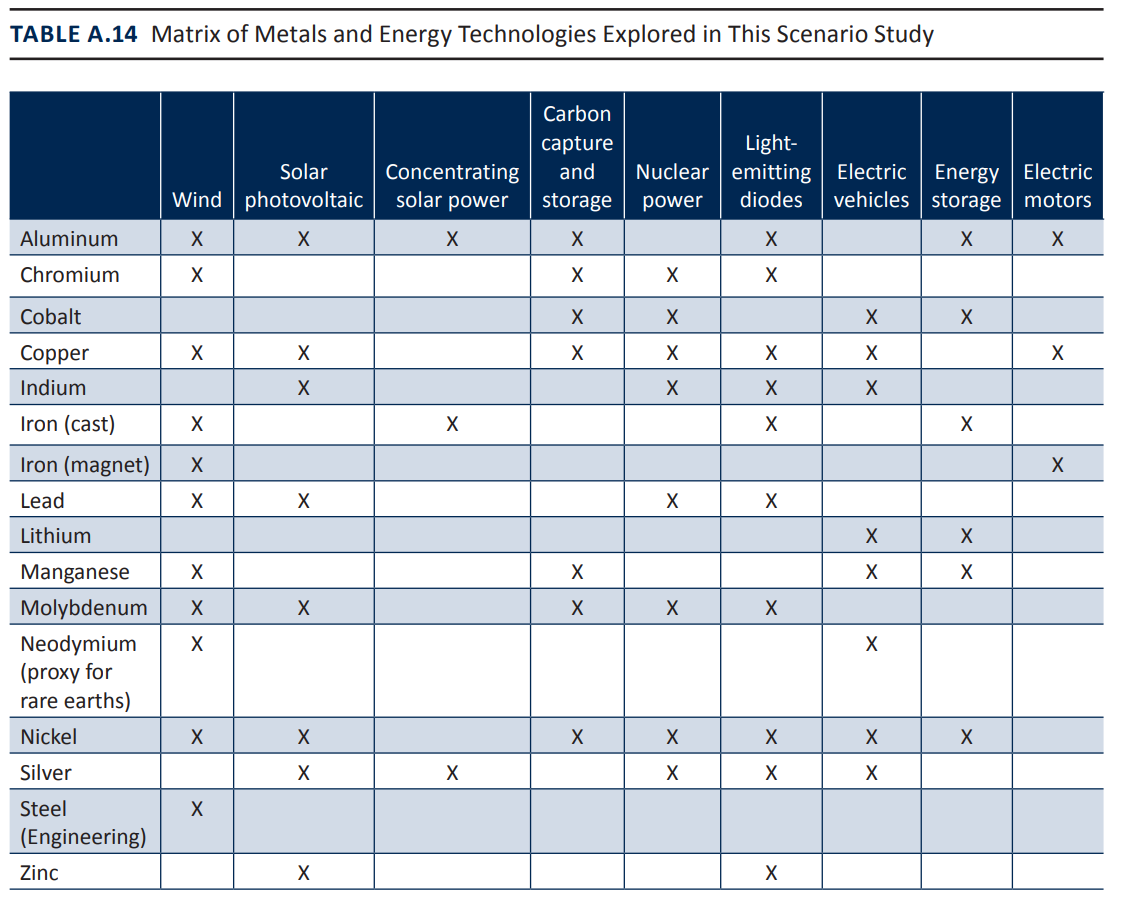

Instead of burning oil, gas, and coal in power plants, we need materials for wind turbines, solar panels, heat pumps, and batteries to meet our energy needs. Electrifying transport and infrastructure also means a sharp increase in the required minerals and metals, and various metals are needed even for capturing and storing greenhouse gases.

According to the International Resource Panel, resource demand is expected to increase by 60% by 2060. A significant portion of this increase is attributed to the energy transition. This is concerning, especially considering that between 2016 and 2021, the world economy has already used nearly as much material as in the entire 20th century. I can’t stress that too often…

Dirty and dependent resources

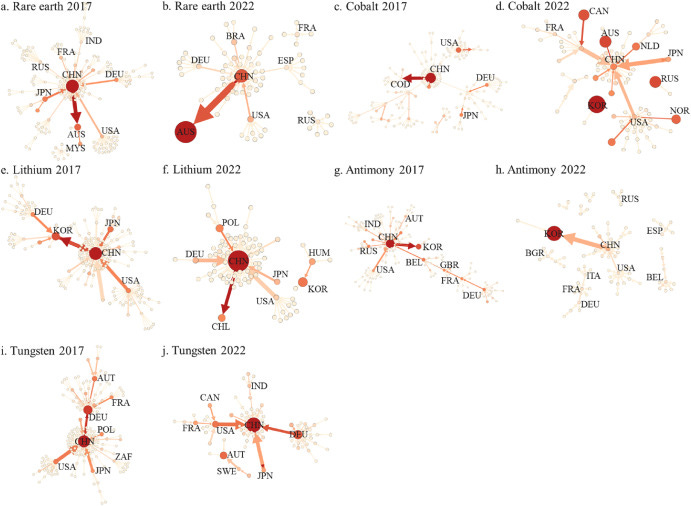

Without guiding policies, the transition to clean fuel will be accompanied by significant "pollution" in other areas. Mining is not only physically polluting but also lacks safeguards for human rights, as seen in cobalt mines. Moreover, the largest reserves of resources are located in countries where Western nations prefer not to be dependent. Global interdependencies seem to shift according to very recent research. The findings suggest that the global network of critical metals interdependence has weakened. China and the U.S. are moving towards separate spheres, contributing to a division in the global landscape. Furthermore, there's a diminishing reliance on China globally, although China itself is increasingly reliant on the world. China remains the primary global player in lithium and tungsten alone, yet it's the most globally dependent nation across all four critical metal interdependence networks, except for tungsten. Concurrently, China and Western nations like the U.S. face significant vulnerabilities in their critical metal supply chains, while others show improvement. Notably, there's a robust interdependence between MSP (Mineral-rich Sub-Saharan African) countries and China. The dependency of MSP countries on China has notably reduced, whereas China's dependence on MSP has deepened gradually.

Even if mining becomes less polluting, it will still result in biodiversity loss due to earth disturbances, not to mention energy consumption, which accounts for about 11% of the global total. Only by imposing stricter requirements on extracting critical minerals and metals essential for the energy transition and opening mines closer to home can a "cleaner" sector emerge.

Clean and circular

So, what are the solutions? Should we halt the entire transition, especially in a period where global support diminishes? In a world where new temperature records are set almost daily, that's not an option.

If done correctly, we can replace consuming new, finite resources with a limited amount that can be reused to tap into nature's infinite energy. This requires an integrated, innovative, and circular approach. For instance, it would have been beneficial if we had designed the first solar panels and wind turbines with reuse in mind. Recycling proves challenging because we failed to do so, although theoretically, 85% of a wind turbine can be reused.

But there's more. The best way to prevent the harmful effects of resource extraction is by not having to extract them in the first place. There are several possibilities, some of which we already partially implement. Firstly, reclaiming resources from discarded items reduces the need for new extraction. This needs to be done on a larger scale. To encourage this, more standardization is needed, such as the mandatory USB-C port in the latest iPhone from Apple. As mentioned, we should consider this in the design of our products. More obligations to make devices more accessible to disassemble and separate materials are crucial to making recycling easier. Transparency will also facilitate recycling. Where are certain materials located? A materials passport would be helpful in this regard.

Is that all? No, enabling repairs better also helps. Take the sustainable Fairphone, where all modules can be replaced. Making it possible to replace with new, technologically better components can prolong product lifespan. Ultimately, the ultimate solution to reduce the need for further resource extraction is a smaller demand for energy. Europe has shown that it is possible to be more energy-efficient when compelled to do so. Price incentives work!

Is it possible?

The recent Global Resources Outlook has a (very, very) challenging scenario where resource use can become more sustainable without harming growth. Their Sustainability Transition scenario takes four policy packages, which would lead to more sustainable outcomes. It requires some courageous assumptions (especially at this time), for example, on effective (global!) policies on carbon and resource pricing, innovation policies and the funding of it. I looked into some of the details and can not understand how they came to this conclusion. There is more than efficiency and pricing, and if you want behavioural change, you probably should do more than that.

Such policy packages and scenarios are not wrong. The results are presented in rather optimistic language, heralding the fact that the economy can grow.

However (and that is not explicitly in the report), all these policy packages are not enough to reduce the material footprint (see figure); it leads to an increase of 20% instead of 60%.

It does not help biodiversity loss; it is even questionable if this will happen. So without it is written very clearly in the text: this most extreme, optimistic technocratic scenario where many crucial assumptions are assumed away or changes taken for granted, is not enough to get to a global economy within planetary boundaries. Shocking.

I want to give a more detailed comment, but there is not enough detail to completely understand what they have done.

This is a ‘within-system’ approach to making an unsustainable system more sustainable. However, it will not work unless we discuss the underlying structures concerning the economy's demand side.

It is possible to have an energy and a resource transition that works for all. But it requires more. Much more. It requires that we start with those boundaries and work from there, with realistic assumptions how we can create a thriving planet and a society that works for all. A complete overhaul of our systems, where material economic growth is a result, not a starting assumption. If the consequence is less economic activity aligned with our primary objective: to have a livable planet.

For me, an energy transition not only entails more renewables and pricing of negative externalities to get a transition done. It also requires behavioural changes and a more radical overhaul of economies: demand reduction is a crucial part of the mix. But that will only happen if more is not needed anymore for everyone. It is about the growth paradigm

Where there's a will, there's always a way. But it's crucial to keep looking around as you tread that path.

This blog is partly based on this article in Het Financieele Dagblad (in Dutch)

Great read.