Hi all,

Since I lowered the frequency of this newsletter, I have always worried that I will miss out on telling someone urgently or not being on the news. So much is happening that it feels like change is accelerating — although not necessarily for the better. Yes, Trump, European deregulation tendencies (if regulation should only enable competitiveness, it is about having a future!), wars, climate disasters, you know it all. And since you know it all, I don’t have to write about it in this newsletter. It will be more about the longer-term system stuff, and I will try to bring some perspectives together in a coherent story to find some root causes.

Just a warning: the whole story is rather lengthy. So, I'll start with a summary of the main points, if that's okay with you. The rest of the (more detailed) story follows below. Over the years, I have learned that not everyone is interested in nerdy stuff like causal loop diagrams or details about policy proposals.

(In the meantime, you can always listen to our podcast for other perspectives on the news (and my good and bad news of the week). We discuss many topics, including our tipping point research, which I discussed in this blog two weeks ago. This week’s episode was also interesting about private finance and weapons.)

In the last few weeks. I have seen (as every year) much attention for the World Economic Forum’s Global Risk Report. Essentially, it is a survey among experts. In these kinds of reports (even among experts!), you always see that current worries and risks are overweighed. Hence, a longer-term perspective on these reports and the reported risks helps (like I did last year).

However, the conclusions are straightforward: optimism in the (Western) world fades, risks related to nature rise (from long-term concern to urgent reality, as they state), and solutions are getting more complex. Most respondents expect a more polarised world in the coming years, with significant risks of cyber-wars and state-armed conflicts.

Everyone (at least on LinkedIn) copy-pastes the five risks (long- and short-term). However, for me, the figure below is more important. It shows (again) the interlinkages of all risks and the polycrisis unfolding before our eyes.

This is nothing new for the regular reader of this blog. We live in a complex, interconnected world, yet we want to use a reductionist approach to handle everything happening.

That might also be one reason all these worries, risks, or warnings have not led to action.

There’s more at play here than simply "not caring." This seems to reflect mounting tensions, a transition where the battle for the favour of the silent majority has become increasingly fierce.

There’s clear evidence that a growing minority does want to act. They want to live more sustainably, consume less, and reduce their climate impact. And change doesn’t even require a majority; a substantial minority can shift norms and drive progress toward sustainability. See also my previous post.

This inevitably provokes resistance. Opposing the growing minority is a vocal and determined group committed to maintaining the status quo. This coalition includes vested interests in the current system, climate deniers, and those disillusioned with everything. Clinging to their entitlements, they fiercely resist change. For now, they hold the political upper hand.

These feedback loops against transformation arise from a mix of opposing forces, which I’ll explore below. The resistance itself has sparked debate. If societal divisions deepen or opposition intensifies during a transition, that 25% support we also used in our research as a social tipping point for norm shifts may not hold. It could grow in response to change, but in an increasingly fragmented society—where social media amplifies ideological bubbles—the overall 25% figure may obscure more nuanced shifts in societal norms.

Why is this relevant? There are many signs that the structure of our economy is rapidly changing. A changing economic structure (or should) leads to changes in power structures between labour and capital, countries, and firms. Without institutional change, this leads to outcomes where not everyone will be happy. A third industrial divide is such a struggle, that we might be right in now. Below, I’d like to explain this more elaborately.

If this is the case (as I believe it is), what is required is an agenda for radical, fundamental change. In the last few weeks, a few papers (like this one from Kallis et al. and this one from Hoffenberth) give an overview of what economic structures might look like in a society where everyone has a decent life within planetary boundaries. I know, some think now this is a buzzword sentence. For me, this is what it is all about. Can we enable societal change for a better future for all instead of a better life for a few who already have more than enough? Also, I'll be sure to dive deeper into that part.

For people who don’t want to read all the nuanced stuff below, the summary is quite simple:

The story on social tipping points is probably more complicated than ‘25%’.

We live in times where economic structure changes big time. Together with sustainability crises and all that is happening, this gives reason to believe that we see a seismic shift in almost everything (with no guarantee that it will be better)

There is a policy agenda for life within planetary boundaries for all. We see different heterodox ideas emerging as Post-Growth Economics.

So, the path to travel will not be easy. To make radical ideas more mainstream, we need more convinced people, more sustainable innovation, and institutional change, while resistance will also increase. A hell of a job. But it is the only way.

Feedback loops against change

Based on the paper by Eker et al. (2024), I want to schematically highlight what we are dealing with (see figure below). A so-called causal loop diagram highlights the interactions that can either strengthen a part of the population that favours a transition but also interactions and feedback loops that hinder change. Practically, it is relatively simple. The enforcing feedback loop (Left upper side) is where we typically concentrate on a sustainability transition: the part of the population in favour of change, and the more significant that group gets, the more regulation will be pro-change. Technological sustainability innovation and regulation make sustainable businesses more competitive, so they can scale up (lower left side). This has positive effects on the number of pro-change people. However, another loop is working extremely hard right now: those that resist change are resisting harder now, maybe because the left-hand positive feedback loop is threatening business interest (lower right side). The two loops work against each other and lead to value polarisation. That is where we are right now.

This fierce resistance is understandable. In every significant transition, a similar pattern emerges: as new ideas gain ground, opposing forces grow stronger. Tensions rise because one side develops an increasingly powerful and hopeful vision for the future, with more technological solutions available while the other clings to the status quo. The latter often accuses progressives of being negative and wanting to take away life’s joys—no barbecues, no flights, no fun. It’s easy to paint an intimidating picture of an old, communist-like future where everything is mandatory and nothing is allowed.

You could say something similar about the conservative or opposing camp. They rely on a mix of techno-fantasy—optimism about nonexistent technological solutions—and denialism, burying their heads in the sand when confronted with issues. This might help in the short term but is disastrous in the long run.

In rising tensions like this, humanity teeters on a fine line between a catastrophic future and inching toward a better world. I can’t predict which way the balance will tip. But I’m glad to see more people refusing to give up.

Because of that slow progress, every ounce of energy is needed now more than ever. Not to convince the naysayers and science deniers—they’re beyond reach—but to guide the significant, silent majority step by step through this transition. The red line in the middle is what it is all about. That’s where real change can happen.

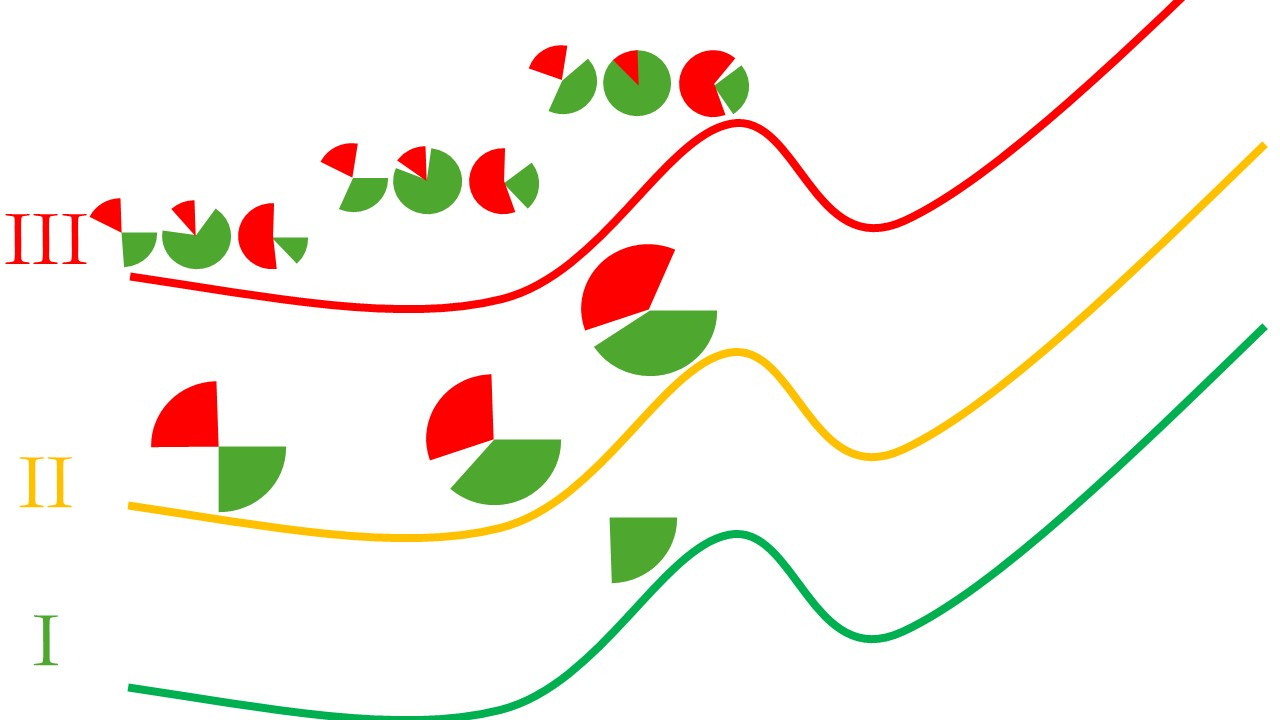

The story is that 25% of the population is a good indication of a social tipping point. I have written about it before. This would suggest that if the group of people favouring the causal loop diagram is 25%, new norms can become dominant. However, nowadays, we could question whether that will be the case. There are two reasons for that; see the figure below.

Let’s start with the standard idea: we need 25% (see curve I below): if we reach the 25%, we’ll have a tipping point. However, if all developments lead to more polarisation than before, resistance will increase. This is depicted in the figure as curve II. If resistance increases, we need more people in favour of a tipping point to counterbalance the negative feedback loop. Hence, some changes might need more than 25% to succeed. In other words, the critical group you need in society depends on the polarisation in society.

Second, in a society where distinct social groups interact less with each other than before (because of geographical segregation as in the US or segregation by educational level as in the Netherlands or because of social media echo chamber segregation), the relevant metric might not at all be 25% It might be the case that 90% of one group is convinced, but no more than 10% of another group. This is in the figure depicted in curve III, with three distinct groups that only interact limitly. During the transition, every group changes; the one in favour (the middle one) gets, in the end, 90% convinced. However, the group that is against will become 70% against, while the group in the middle changes slightly. My underlying assumption here is that we need, to reach a tipping point, also in total more persons in favour than (firmly) against in every group. Then, the resulting tipping point becomes less obvious: it depends on the dynamics within each group.

The uncomfortable answer of this complex reality is that, in current times, to have broad-based norm shifts, empirical research about smaller changes probably do not give the whole answer.

Throughout history, major changes have always begun with a small group unafraid of being unpopular. And yes, the future may not be more enjoyable, but it will be more dynamic. Transitions are rarely pleasant. They’re sharp, painful, and uncomfortable. But as always, chaos eventually gives way to something new. Let’s hope that something is better.

The third industrial divide

In his article Brave New World, Herman Mark Schwartz revisits Michael Piore and Charles Sabel's 1984 work, The Second Industrial Divide, which analysed a pivotal shift from craft to mass production in the early 20th century. They argued that the rigid structures of mass production made economies vulnerable to various shocks, leading to a crisis in the 1970s and 1980s. Piore and Sabel proposed a move towards "flexible specialisation"—smaller firms utilising general-purpose equipment and fostering egalitarian workforces—as a resilient alternative. However, Schwartz notes that this vision did not materialise as anticipated.

Five Critical Errors in Piore & Sabel’s Analysis

Ignoring Firm-to-Firm Competition – They focused on labor vs. capital but overlooked how firms fight for profit through monopolies and intellectual property.

Misreading Vertical Disintegration – Instead of fostering egalitarian networks, outsourcing created new hierarchies where lead firms dominate dependent subcontractors.

Underestimating Corporate Innovation – They emphasized small entrepreneurs but ignored large firms’ systematic R&D as a driver of technological progress.

Neglecting Financialization – They missed how shareholder value and financial markets would drive corporate short-termism.

Overlooking Geopolitics – They failed to see how state-driven research and global competition shape economic transformation.

Without going into detail here, we did not get smaller firms. On the contrary. New research indicates rising concentration under most specifications. They tested numerous specifications and also different geographical areas. They found that the average concentration across countries increased by five percentage points between 2000 and 2019, with notable differences across geographic competition levels.

Today, Schwartz identifies a similar inflexion point, suggesting we enter a "third industrial divide." The growth wave initiated in the 1980s, driven by information and communications technology (ICT) and early biotechnology, is now experiencing endogenous decay. This decline is not solely technical but reflects an erosion of the social and political foundations supporting this growth era. Contemporary challenges—geopolitical tensions, threats to democratic governance, economic stagnation, and global health crises—mirror past crises and indicate a transformative period in the global economy.

Hence, this analysis is more or less an explanation of the observations of the World Economic Forum.

Schwartz emphasises that these macro-sociological inflexion points open political and social restructuring opportunities. The outcomes of current struggles among workers, firms, and social groups will shape future economic growth, income distribution, and power dynamics. Reflecting on Piore and Sabel's analysis provides valuable insights into understanding the present decay and potential pathways forward as we navigate this emerging industrial divide.

Today, as automation, AI, and digital platforms reshape industries, these same dynamics persist. Tech giants, not decentralised networks, control the economy through patents, platforms, and data monopolies. Financialisation continues to drive short-term decision-making, and geopolitical rivalries influence technological development. Understanding these forces is crucial for shaping a more equitable and sustainable industrial future.

An agenda for radical change

Apart from the social tipping points that drive norm shifts (or not) and understanding the economy's structure, we also need to know where to head. And about that path forward, I have read two new, comprehensive articles under the header post-growth, which bring together the debate about radical change and also an academic theory on how to get there.

In a recent publication in The Lancet Planetary Health, researchers have delved into the intricate relationship between economic growth and planetary health, proposing a comprehensive policy agenda to harmonise human development with environmental sustainability. As the authors state (and I use the full, lengthy quote here):

Post-growth research can be seen as part of sustainability science that is influenced by—but not constrained within—ecological economics, drawing from different traditions and contributing to the construction of a new economics that brings interdisciplinary (eg, ecological, anthropological, historical, sociological, and political) insights into our understandings of how human provisioning works. Post-growth emphasises independence from—or prosperity without5—growth, and serves as an umbrella term encompassing research in Doughnut and wellbeing economics, steady-state economics, and degrowth. Doughnut and wellbeing economics call for the satisfaction of basic human needs and high wellbeing within planetary boundaries, whereas steady-state economics emphasises the need to stabilise societies’ resource use at a relatively low, sustainable level. Doughnut, wellbeing, and steady-state economics generally position their proposals within the current capitalist system, whereas degrowth is critical of the possibilities of an egalitarian slowdown within capitalism given that capitalist competition is structurally geared towards growth. Degrowth therefore emphasises the need for a planned, democratic transformation of the economic system to drastically reduce ecological impact and inequality and improve wellbeing. Degrowth, similarly to steady-state economics, regards a lower GDP as a probable outcome of efforts to substantially reduce resource use.6 Reducing GDP is not a goal of these approaches, however,5 but, it is seen as something that economies need to be made resilient to. The Doughnut and wellbeing approaches are more agnostic about GDP growth, but still view it as a poor measure of progress. Post-growth is plural and open to all these perspectives. All approaches converge on the need for qualitative improvement without relying on quantitative growth, and on selectively decreasing the production of less necessary and more damaging goods and services, while increasing beneficial ones.

It's not about rejecting growth entirely but about creating an economy that isn’t dependent on it. This may seem like a subtle distinction, but in practice, it makes a profound difference. The study underscores the pressing need to reassess traditional economic paradigms prioritising GDP growth without accounting for environmental degradation. It highlights that unchecked economic expansion often leads to resource depletion, biodiversity loss, and climate change, which threaten human health and well-being. It's nothing new for the regular reader, but it's still worthwhile reading this article. Very nuanced and convincing

To address these challenges, the authors propose a multifaceted policy agenda (which is not so revolutionary in ideas):

Redefining Progress Metrics: Transition from GDP-centric evaluations to more holistic indicators that encompass environmental health and social well-being.

Implementing Sustainable Production Practices: Encourage industries to adopt eco-friendly methods, reducing carbon footprints and conserving natural resources.

Promoting Circular Economy Models: Advocate for systems where waste is minimized, and materials are reused or recycled, thereby reducing environmental impact.

Strengthening Environmental Regulations: Enforce stricter policies to protect ecosystems, including pollution controls and conservation efforts.

Investing in Green Technologies: Allocate resources to develop and deploy technologies that mitigate environmental harm and promote sustainability.

Fostering Global Collaboration: Encourage international cooperation to address transboundary environmental issues and share best practices.

Enhancing Public Awareness and Education: Inform and educate the public about the importance of sustainable living and the impact of consumption patterns on planetary health.

The proposed agenda calls for a paradigm shift in policy-making, urging leaders to integrate environmental considerations into economic decisions. By adopting these recommendations, societies can work towards a future where economic activities support, rather than compromise, the health of our planet and its inhabitants.

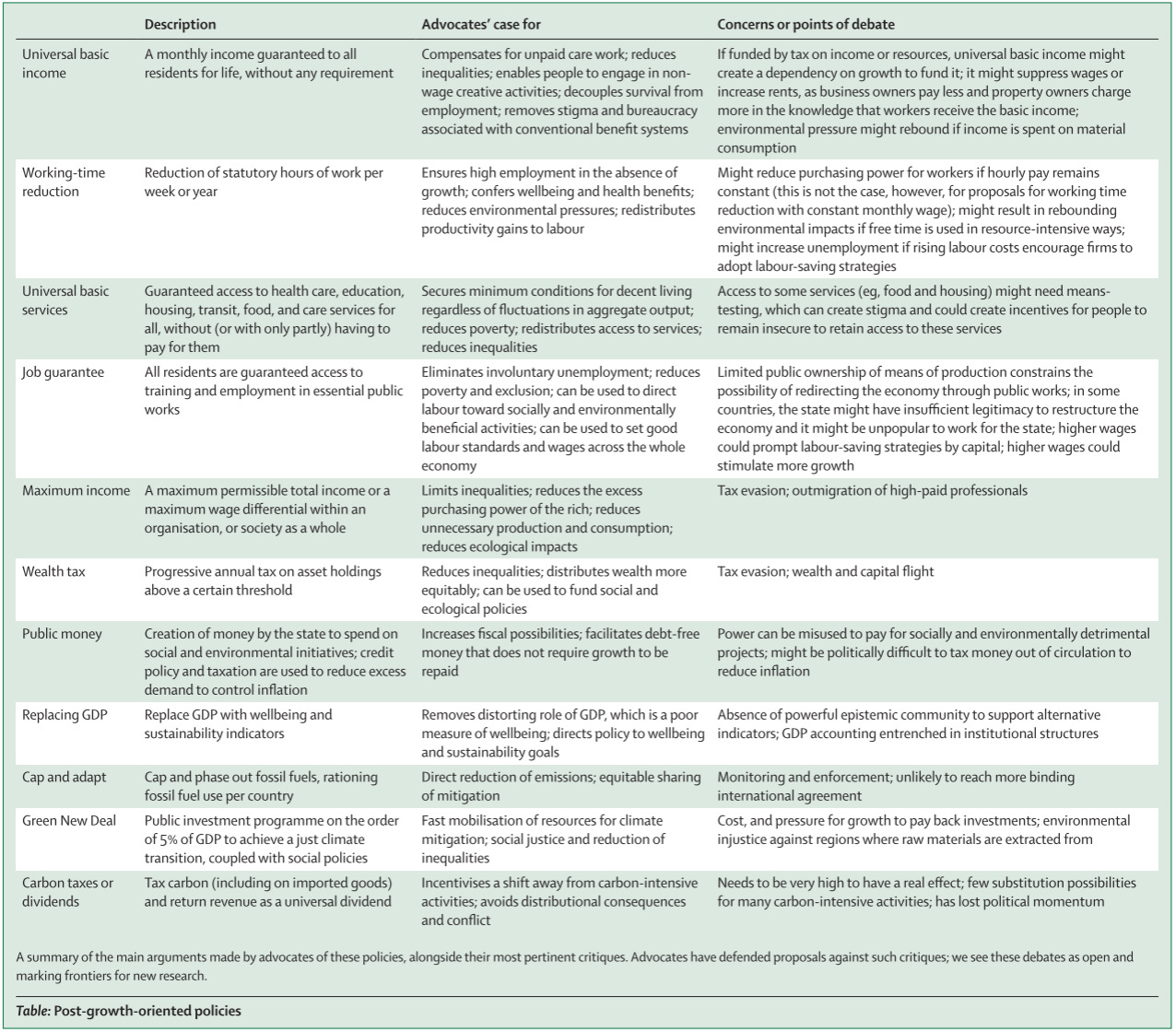

I especially liked the table below. It provides a very handy overview of policy proposals. What is also perfectly clear is that all these proposals (most of them also very old!) are controversial.

I will not discuss all policy proposals; all of them would need different, separate posts.

Another recent paper also discusses the structures that need to change to transition towards a post growth economy. To be honest, this paper is even more radical (or heterodox) than the one I discussed before. I agree that our current market economy (or capitalism) has growth imperatives, such as profit accumulation, accelerating basic needs (beyond productive capacities), financialisation and rentierism. Hence, we need to discuss the structure of our economy.

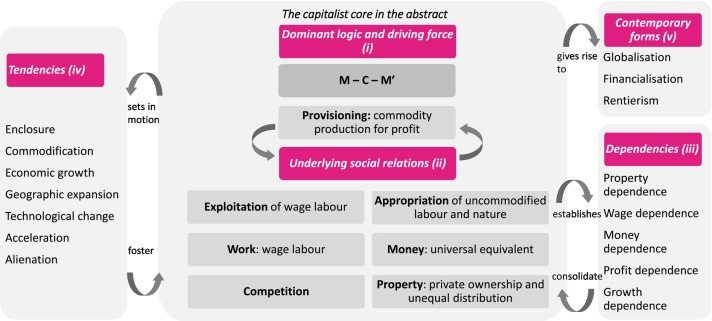

This figure from the paper provides a systemic breakdown of capitalism, illustrating how its core elements interconnect to sustain economic growth. At its foundation lies capital accumulation and profit maximisation (and the institutional dependencies through basic needs and government budgets are missing), which drive firms to expand continuously in pursuit of competitive advantage. This creates an inherent dependency on growth, making economic expansion a choice and a structural necessity.

Underlying social relations support this growth imperative, including private ownership, wage labour (the fictitious commodities of Polanyi), and financial mechanisms that reinforce inequality and perpetuate the need for continued expansion. These structures, in turn, create systemic dependencies—capitalism relies on mass consumption, financial markets, and the commodification of nature and labor to function. As a result, attempts to slow or reverse growth face significant resistance, as they threaten the very foundations of the system.

Emerging from this foundation are distinct tendencies, such as financialisation, globalisation (see here the explanation of what happened in the second industrial divide), and technological innovation. These forces accelerate capitalism’s growth dependence, often worsening environmental degradation and social inequalities. Finally, capitalism takes different forms over time—whether in its neoliberal, digital, or industrial variations—shaping the specific challenges and opportunities for systemic transformation.

By mapping out these interconnections, the figure underscores that growth is not an optional feature of capitalism but an embedded outcome of its structure. Consequently, a post-growth transition cannot rely on incremental reforms alone; it requires fundamental shifts in ownership, labour organisation, and financial systems to break capitalism’s dependency on perpetual expansion. In short, this may not be the end point but it is a transitional idea to get at least some traction.

To return to the feedback loop and tipping points above, this agenda needs some groundwork to gain more fans. Using the causal loop diagram, it is clear where it should come from: thought leaders, innovation, regulation, and…crises.

I’m sorry, it was a long read. Hope you enjoyed it.

Be nice

Hans

Thankyou Hans, I have been reading your posts for a few months now and really appreciate them. You capture and explain the important and difficult topics so very well. I spent 3 years writing posts about the great Transition and ran out of energy in 2023. I came to the realisation that it is very unlikely that civilisation will proactively transition in a sensible way, things will need to break before the openings for the new truly emerge. This process will be difficult and probably unevenly distributed. I'm now devoting my efforts to helping people, organisations and communities to build adaptive capacity and resilience. It turns out that much of this is about trying to become better humans with greater empathy, acceptance, ethics... and increasingly intelligent about seeing the opportunities as they emerge. Your writing helps build the awareness, thank you very much and please continue.

Thanks! Very good all of it! I love the quote by prof. Kevin Anderson: there are only radical futures. Either we transform in a radical way or the planet will do it for us.

(I mean “love” =find it useful, not loving the prospects of our futures)

In my book many incentives are totally useless when not looking at it this way, and others make totally sense!