#11 Leverage points to get rid of asymmetric finance

Why financing extraction is no problem, but financing restoration is

Hi all,

Sometimes, individuals appear to believe that simply adding more information to a system will inherently precipitate change. For instance, disseminating information regarding the health risks associated with smoking or overeating may prompt individuals to modify their behaviour for their benefit. Similarly, highlighting the adverse impacts of certain investments could alter the direction of financial flows.

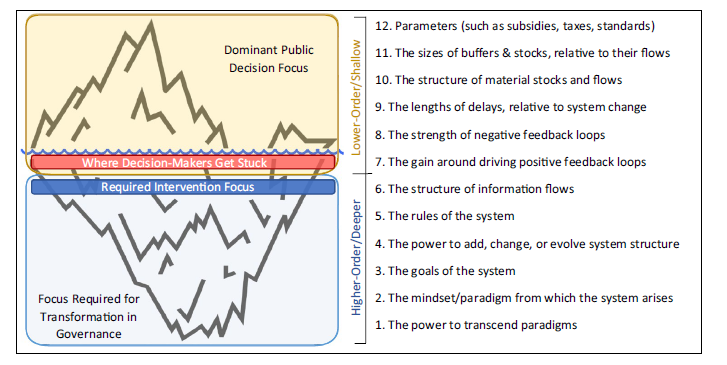

This approach may yield results intermittently. Donella Meadows identifies introducing new information into the system as a leverage point of moderate significance. Leverage points represent junctures within a complex system (such as a corporation, an economy, a living organism, a city, or an ecosystem) where a slight adjustment in one aspect can trigger significant changes across the entire system.

However, this assumption overlooks a crucial aspect of the financial system. Financial participants are primarily motivated by the pursuit of maximum returns, rendering it improbable for them to stray from profitable practices. If engaging in harmful activities proves more financially rewarding than pursuing beneficial ones, what incentive do they have to choose otherwise?

This quandary lies at the core of what I refer to as the "asymmetry of finance": profits can be easily generated by exploiting non-priced resources or utilising cheap labour, whereas investing in sustainable alternatives often yields lower returns. Furthermore, while the relationship between risk and return is well understood, with individuals being educated and regulated when making investment decisions, the same cannot be said for considering positive or negative impacts.

Unfortunately, there's a shortage of willing volunteers ready to bear the costs of addressing these imbalances, even when they understand the repercussions of investment decisions. In situations like these, akin to many intricate systems, more than relying on one leverage point may be needed. We must delve deeper, exploring additional leverage points for systemic change.

However, since this system is a product of our creation, we retain the ability to dismantle it. We must take decisive action without delay.

Impact-risk-return

A classic mantra (at least here at Triodos Bank) is the triangle of impact-risk-return, also called the investment trilemma. While, as everyone knows, the relationship between risk and return is fixed in terms of how to calculate, what assumption you can make and what evidence you have, it is not related to impact. And where there is (at least ex-ante) a well-known trade-off in the case of risk and return, it is less clear, especially in the longer run, how this relates to impact-risk-return.

And although we have many rules to assess return and risk (appetite), it is not to say it is ‘objective’ in any way. It depends (forward-looking) on our assumptions of expected profit growth, risks and discount rates we use. As said in a previous newsletter, discounting the future is always a normative exercise.

If you conclude that results are the only source of ‘truth’ about your investments, I would also doubt it. First, they only say something about the monetised part. Second, they tell only the story of realised returns, where you cannot ultimately disentangle the risk and return relationship. How often is it not found that expected returns deviate from realised returns while not equal expected risk differentials, for instance, between bonds and equities?

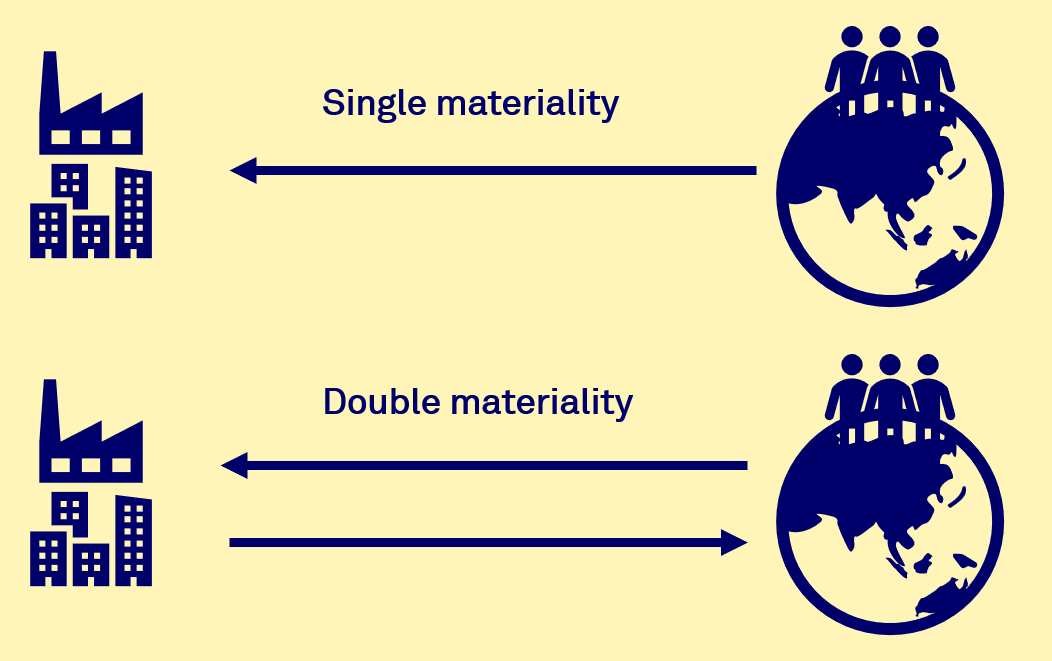

The relationship with sustainability becomes even less clear. ‘Sustainability risks’ are often defined as material risks from outside to businesses (or investments). The notion stems from the broader concept of materiality in financial reporting, which traditionally focuses on determining whether information would influence stakeholders' decision-making process.

However, double materiality also includes businesses' impact on the environment and society. It considers how a company's operations, products, and services contribute to sustainability challenges.

But how we should measure this, what the intentions are and how exactly financial institutions should report on it, still needs to be completely clear. In Europe, regulations like CSRD, SFDR and taxonomy will help to give more clarity in the coming years.

But the point I want to make is that even if we have to complete insights (which can take years, and the bias is now that only sustainable finance needs to disclose, while it is much more critical that unsustainable finance will disclose harmful impact), more is required—the reason: the asymmetry of finance.

Dilemma of Asymmetric Impact

Because it's relatively easy to get financing for nature destruction, even if the effects are known; after all, a dead tree is financially more valuable than a living one. You can make planks, a table, a chair, and so on from a dead tree. All of these can be sold for profit. A living tree, at most, produces fruits that you can still do something with. At most, because in many cases, one tree's economic and financial value is minimal. And then there's another reason to remove those trees: the land. By removing trees (without fruits) from the land (or burning them), the land can be cleared for (monoculture) agriculture such as palm oil. See, then the land generates some financial return. What applies to a tree applies to nature: if the adverse effects don't cost anything, it's a free lunch for the financier.

The opposite is more challenging. If restoring nature costs money, it will only happen sometimes. The values created, or the positive impact, result in better nature but only a limited cash flow, which is necessary for private financing.

This asymmetry in financing is built into our rules. Only monetized cash flows (for example, by selling carbon credits for future nature restoration) make financing with a certain return possible. Another option is to buy land with gifts or low-interest loans and then engage in less intensive (or regenerative) agriculture. This lowers the required return, making it possible to restore nature.

Deeper leverage points

Of course, some financial institutions, like Triodos Bank and other banks belonging to the Global Alliance for Banking on Values (GABV), want to create a positive impact. And, of course, we do so. But it is simply not enough. By any measure, you can find that there goes much more capital to destruction than restoration. Whether for climate mitigation, adaptation, biodiversity loss, regenerative food systems or the SDGs, the ‘missing’ is in the billions of dollars globally.1 Every year.

Transparency as the only actively used leverage point is definitely not enough. To return to my examples in the introduction, you inform people that smoking is bad, but you don’t raise the price of cigarettes or change the availability or where they can smoke. We realised a long time ago that we have to do all of this.

So, let’s take Donella Meadows's leverage point framework (sometimes translated as an iceberg) and see what is needed to eliminate asymmetric finance.

But which leverage point should you get this attention from me? Bolton (2022) has some new ideas about how to approach that. Applying a purist approach, one would adopt the leverage point hypothesised to be most impactful: transcendence of paradigms (figure below). In the case of the financial sector, for example, start banking with different values than financial values, or be satisfied with a lower expected return.

However, transcending paradigms in such a way is arguably out of reach with policies, and thankfully so, as some might question the legitimacy of non-elected officials seeking to drive the transcendence of paradigms within public decisions. One could apply the leverage points that all or most of the decision-making influences interact with, the power to alter system structures and reinforce feedback loops. However, given that any change made within these leverage points would still be operating at the level of the existing dominant system dynamics, it is arguable that the system will respond by seeking to restore its current equilibrium.

Instead, efforts could be focussed on the leverage points one step deeper than each of those considered to have the potential to be universally active within the current decision-making system, together with altering the more shallow leverage points. Applying deeper combined with shallow leverage points could drive system change by effectively disturbing the status quo just enough to override it. Hence, a one-deeper approach may balance the practical constraints and considerations of decision-making for investing in a transformation and combating asymmetric finance. Some ideas:

Parameters: Numbers (such as subsidies, taxes, standards)

Example: Increasing taxes on carbon-intensive investments and offering subsidies for renewable energy projects can redirect financial flows towards more sustainable industries, reducing the carbon footprint.

Buffers: The sizes of stabilizing stocks relative to their flows

Example: Establishing financial reserves for green investments can provide a buffer that supports sustainable projects through economic cycles, enhancing their resilience. The other way around, brown capital requirements (for more unsustainable investments (as reported once we have transparency), might also make sustainable alternatives more attractive.

Stock-and-Flow Structures: Physical systems and their nodes of intersection

Example: Developing green bond markets that fund projects with environmental benefits can create new financial flows that support sustainable infrastructure, like clean energy and public transportation.

Delays: The lengths of time relative to the rates of system change

Example: Implementing more extended maturity periods for sustainable investment funds can encourage long-term thinking and stability in environmental initiatives, aligning investment strategies with sustainability goals.

Balancing Feedback Loops: The strength of the feedbacks relative to the impacts they are trying to correct

Example: Introducing sustainability-linked or impact-linked loans with interest rates that decrease as the borrower meets specific environmental targets can create financial incentives for companies to pursue sustainable practices.

Reinforcing Feedback Loops: The strength of the gain of driving loops

Example: Encouraging investment in sustainable funds that outperform traditional funds (in the longer term) can create a reinforcing loop, attracting more investors to sustainable options.

Information Flows: The structure of who does and does not have access to information

Example: Mandating comprehensive sustainability reporting for all publicly traded companies can improve information flows (CSRD), allowing investors to make more informed decisions aligned with sustainability—also mandatory reporting by investors (SFDR, Taxonomy) for the same objective.

Rules: Incentives, punishments, constraints

Example: Implementing regulations that penalize financial institutions for investing in environmentally harmful projects while rewarding sustainable investments can shift the entire sector towards greener alternatives.

Self-Organization: The ability of a system to structure itself

Example: Supporting the formation of coalitions and networks among sustainable investors and financial institutions can facilitate the exchange of best practices and innovative financial products that promote sustainability.

Goals: The purpose or function of the system

Example: Redefining the financial sector's goals to prioritize sustainability alongside profitability can transform investment strategies to support long-term environmental and social well-being. This is not only a values-based choice; consumer preferences, as well as all other leverage points, can also lead to that.

Paradigms: The mindset out of which the system arises

Example: Shifting the prevailing paradigm in finance from short-term gains to long-term sustainability and resilience can redefine what is considered valuable and worth investing in.

Transcendence: The ability to change paradigms

Example: Encouraging a new generation of financial leaders who prioritize sustainability as a core value can lead to developing innovative financial mechanisms and institutions that support a sustainable future.

By applying Meadows' leverage points to the financial sector, it's clear that strategic interventions at various levels can significantly influence the sector's impact on sustainability. However, it is a mistake to think that one intervention (or, for that matter, a few shallow ones aligned with that) will lead to a change in capital flows. In fact, there is no choice: the only way to overcome asymmetric finance is to pull all levers.

In the news

Global monitoring for biodiversity: Uncertainty, risk, and power analyses to support trend change detection: This is at odds with what we currently do with uncertainty: we treat it as non-existent and implement technical (ex-ante) fixes or optimism about interference so that we do not have to think about adjusting our economic system. This is an existential problem. The only sustainable way to handle this kind of fundamental uncertainty is precaution.

About the Global Resource Outlook: Let’s decouple from decoupling! The Global Resource Outlook is the stark reality that even with stringent global policies, faith in innovation, and sufficiency measures, it's still insufficient to curb resource use. It continues to rise by a staggering 20% from an unsustainable level (See also my previous substack on this).

A report on the AI threats to climate change: Foremost energy, water use, and misinformation.

A report about the development and thoughts of the wealthiest people on earth: In short, you need increasingly more money to be a 1-percenter, and the wealthiest people are worried about climate change but don’t want to fly less in their private jets. There is a long way to go…

That’s all for this week.

Take care.

Hans

Check out $EARTH by Solarpunkdao.earth